|

Fashion on eastern carpets and rugs has spread with Armenian settlement on Polish soil. The partition of Armenia between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Turks in 1080 resulted in the mass migration of the Armenians from their homeland, including to Ruthenia, where Lviv became their main center. In 1356, King Casimir the Great approved the religious, self-government and judicial separation of the Lviv Armenians, and in 1519 the so-called Armenian Statute, a collection of customary Armenian rights was approved by King Sigismund I.

In 1533 Sigismund I sent Wawrzyniec Spytek Jordan to Turkey with the order to buy 28 carpets "for guests treating", for setting tables and "for side eating" of the King himself, besides 100 pieces of eastern fabrics "for wall covering, with flowers and border in the same color, so that they would not differ". Twenty years later, King Sigismund Augustus ordered the same Wawrzyniec Spytek to buy for himself 132 Persian carpets, some of which were intended to decorate the royal dining room. They were to have yellow flowers and "beautiful borders", the others, with an undefined pattern, were intended for the Wawel Cathedral. On April 20, 1553, he received a list of "measure of carpets ... for the need of His Highness." In 1583, in Kraków, Chancellor Jan Zamoyski bought 24 small red Turkish carpets. Persian (adziamskie) carpets were supplied by the Armenian from Caffa on the Black Sea coast who settled in Zamość, Murat Jakubowicz, who on May 24, 1585 received the royal privilege on the Chancellor's initiative to sell "Turkish" rugs in Poland for the period of 20 years. The Zamoyski Inventory from 1601 mentions the "Persian red carpets from Murat" and the "silk carpet from the Turkish tchaoush Pirali" received as a diplomatic gift. In the spring of 1601, Sigismund III Vasa, sent Sefer Muratowicz, an Armenian merchant from Warsaw who served as a royal court supplier, to Persia. "There, I ordered the carpets woven with silk and gold to be made for His Highness, and also a tent, swords from Damascus steel et caetera," wrote Muratowicz in his relation. Not only an excellent warrior, but also a talented organizer, Shah Abbas I of Persia raised the weaving industry to the highest degree. Luxury carpets become a frequent diplomatic gift, and the Shah sent legations to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1605, 1612, 1622 and 1627. In 1603 the Lviv Archbishop, Jan Zamoyski, brought twenty large carpets with Jelita coat of arms from Istanbul for the decoration of the Latin Cathedral in Lviv. In 1612, the young master Pupart donated "a Persian rug, instead of gunblades and gunpowder" to the guild of goldsmiths in Kraków and Bartosz Makuchowicz offered "white Turkish carpet". In the course of three years, between 1612 to 1614, 16 further rugs were given to the guild. The register of movables of Maria Amalia Mohylanka, daughter of Ieremia Movila, Prince of Moldavia and wife of the governor of Bratslav, Stefan Potocki, from 1612 mentions 160 silk Persian carpets "of the most diverse and of the richest eastern work". In the inventory of the Dubno Castle of Prince Janusz Ostrogski from 1616, there are about 150 Persian carpets woven with silk and gold, and the inventory of Madaliński family from Nyzhniv from 1625 mentions "Item carpets: one big and two smaller, three small, two ordinary Turkish, wall hanging varicoloured kilim, red kilim ... " White and red carpets from Persia were particularly popular. Two Persian red carpets were estimated at 20 zlotys in 1641. Before 1682, the priest from Kodeń, Mikołaj Siestrzewitowski, paid 60 zlotys for two cherry carpets. According to the order received from the court of King Ladislaus IV in Warsaw, merchant Milkon Hadziejewicz in a letter written in Lviv on October 1, 1641 to Aslangul Haragazovitch, "Armenian and merchant from the city of Anguriey" (Ankara in Turkey) commissioned him to acquire for "Her Highness the Queen", Cecilia Renata, "one rug of eighteen or twenty ells, silk woven with gold or only silk, it should be a Khorasan rug, so good and so large". According to account by Frenchman Jean Le Laboureur accompanying Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga in her journey to Poland in 1646 on the furnishings of the Warsaw Castle, "furniture is very expensive there, and royal tapestries are the most beautiful not only in Europe, but also in Asia." While Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga herself, writing from Gdańsk to Cardinal Mazarin on February 15, 1646, stated: "You will be surprised sir, that I have never seen in the French crown as beautiful tapestries as here." In the church in Oliwa, according to her account, there were 160 different rugs and tapestries. The act of compromise from 1650 between Warterysowicz and Seferowicz, the Armenian merchants in Lviv, lists in their warehouse 12 large "gold with silk" and 12 small Persian carpets, valued at 15,000 zlotys. Ożga, starost of Terebovlia and Stryi, owned 288 rugs of different pattern and origin: Persian, floor rugs, kilims, silk with letters, eagles, etc. The will of Stanisław Koniecpolski, castellan of Kraków, in 1682 (not to be confused with the hetman, died in 1646) lists two carpets, woven with gold and silver. In the end of the 17th century in Kraków, the varicoloured kilims were valued at 8 zlotys, white and red 10 zlotys, and floral and ornamental at 15 zlotys. In Warsaw in 1696 Turkish kilim was valued at 12 zlotys, the old one at 4 zlotys. Stall keeper Majowicz purchased a Turkish kilim for 15 zlotys. In Poznań, red kilims costed 6 zlotys each, and ordinary were for 3 zlotys in 1696. Armenians settled in Poland, not only traded in textiles, but also participated in the production of carpets. In Zamość, Murat Jakubowicz organized the first manufacture of eastern carpets in Poland. The imitation of Persian patterns was continued in the workshop of Manuel from Corfu, called Korfiński in Brody under the patronage of hetman Stanisław Konicepolski. The register of belongings of Aleksandra Wiesiołowska from 1659, lists 24 eastern carpets and "locally produced large carpets modelled on floor rugs 24". Although traditionally the majority of Persian and Turkish rugs in Poland, or those associated with Poland, are identified as a token of the glorious victory of the Commonwealth, which saved Europe from the Ottoman Empire invasion at the gates of Vienna in 1683, it is more likely that they were acquired in customary trading relations. When in 1878 at the Paris exhibition, Prince Władysław Czartoryski organized the "Polish Hall", presenting, among others, seven eastern carpets from his collection bearing heraldic emblems, they gained the name "Polish."

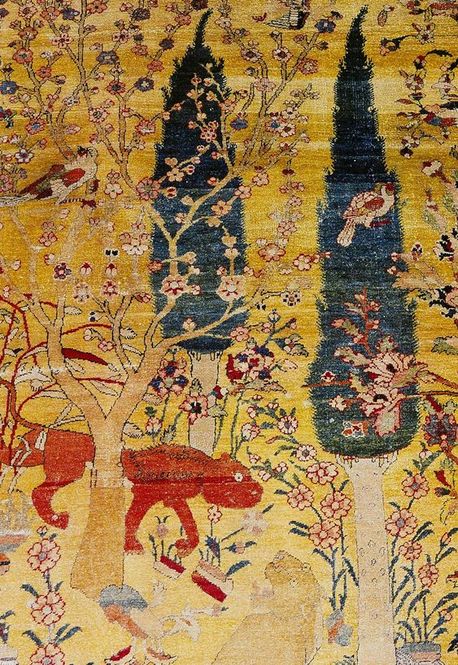

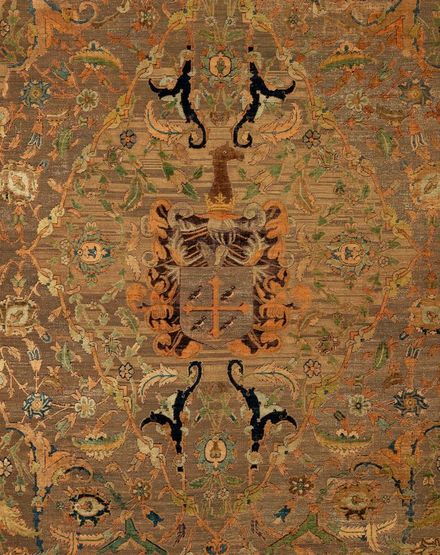

Detail of so-called Kraków-Paris carpet by Anonymous from Tebriz, second quarter of the 16th century, Wawel Royal Castle. According to tradition won at Vienna in 1683 by Wawrzyniec Wodzicki.

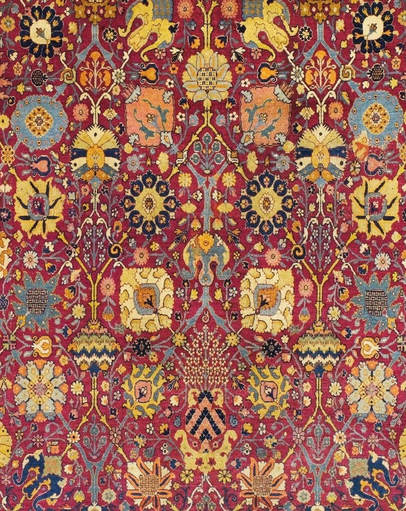

Detail of rug "with animals" by Herat or Tebriz manufacture, mid-16th century, Czartoryski Museum.

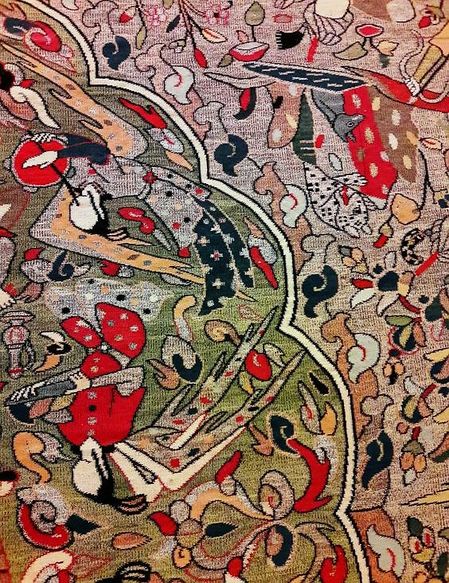

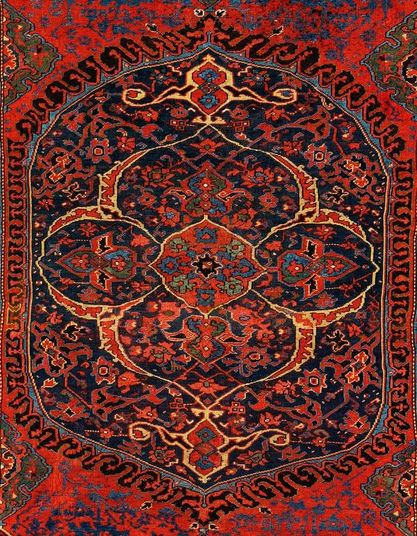

Detail of carpet with hunting scenes by Kashan workshop, before 1602, Residence Museum in Munich. Most probably a gift to Sigismund III Vasa from Abbas I of Persia. From dowry of Anna Catherine Constance Vasa.

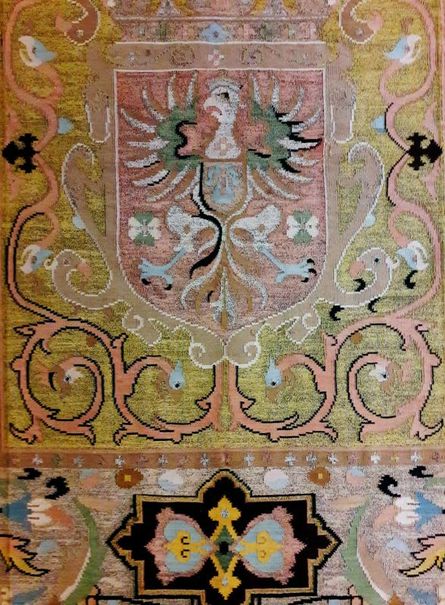

Detail of Safavid kilim with the coat of arms of Sigismund III Vasa (Polish Eagle with Vasa sheaf) by Kashan workshop, ca. 1602, Residence Museum in Munich. Commissioned by the King through his agent in Persia, Sefer Muratowicz.

Mechti Kuli Beg, Ambassador of Persia, detail of Entry of the wedding procession of Sigismund III Vasa into Cracow by Balthasar Gebhardt, ca. 1605, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Krzysztof Zbaraski, Master of the Stables of the Crown in delia coat made from Turkish fabric by Anonymous, 1620s, Lviv National Art Gallery. Zbaraski served as Commonwealth's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1622 to 1624.

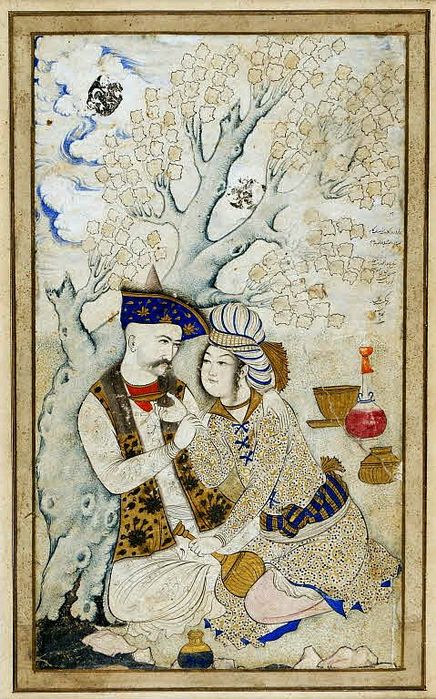

Portrait of Shah Abbas flirting with a wine boy and a couplet "May life bring you all you desire of three lips: the lip of your lover, the lip of the stream, and the lip of the cup", miniature by Muhammad Qasim, February 10, 1627, Louvre Museum.

Portrait of Stanisław Tęczyński by Tommaso Dolabella, 1633-1634, National Museum in Warsaw, deposit at the Wawel Royal Castle.

Detail of Ushak carpet with coat of arms of Krzysztof Wiesiołowski by Anonymous from Poland or Turkey, ca. 1635, Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

Portrait of a lady (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Portrait of a man (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Portrait of a young man with the view of Gdańsk (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Meletios I Pantogalos, metropolitan of Ephesus, during his visit to Gdańsk by Stephan de Praet and Willem Hondius, 1645, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Detail of so-called Czartoryski carpet with emblem of the Myszkowski family of the Jastrzębiec coat of arms by Anonymous from Iran, mid-17th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Possibly commissioned by Franciszek Myszkowski, castellan of Belz and marshal of Crown Tribunal in 1668 (identification of the emblem by Marcin Latka).

Lamentation of various people over the dead credit with Armenian merchant in the center by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1655, Library of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Portrait of Maksymilian Franciszek Ossoliński and his sons by Anonymous Painter from Masovia, 1670s, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Zbigniew Ossoliński by Anonymous from Poland, 1675, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius by Daniel Schultz, 1677, Gdańsk Library of Polish Academy of Sciences.

Portrait of Kyprian Zochovskyj, Metropolitan of Kiev by Anonymous, ca. 1680, National Arts Museum of the Republic of Belarus.

Detail of vase carpet from the church in Jeziorak by Anonymous from Persia (Kirman), 17th century, Private collection.

Portrait of John III Sobieski with his son Jakub Ludwik by Jan Tricius after Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter, ca. 1690, Palace of Versailles.

Detail of medallion Ushak carpet by Anonymous from Turkey, mid-17th century, Jagiellonian University Museum. Offered by King John III Sobieski to the Kraków Academy.

Main religious centers of Poland were also main centers for religious craftemanship in the country. Kraków with its status of coronation city and largest city of southern Poland had an adantage over other locations with the largest number of goldsmiths. A diploma issued in 1478 by Jan Rzeszowski, Bishop of Kraków, Jakub Dembiński, castellan and starost of Kraków, Zejfreth, mayor of Kraków, Karniowski and Jan Theschnar, Kraków's concillors to Jan Gloger, son of Mikołaj Gloger, aurifaber (goldsmith) of Kraków, recognizes Jan as a man of good fame and worthy of admission to the guild of goldsmiths. The document confirms that church had a profound influence on development of this craftsmanship in the country.

Reliquary cross of Andrzej Nosek of Rawicz coat of arms, Abbot of the Tyniec Abbey by Anonymous from Kraków, ca. 1480, Cathedral Treasury in Tarnów.

Fragment of gold reliquary for the head of Saint Stanislaus with selling of a village by Marcin Marciniec, 1504, Cathedral Museum at Wawel Hill in Kraków.

Silver crosier of Bishop Andrzej Krzycki by Anonymous from Kraków, 1527-1535, Płock Cathedral.

Portrait of Primate Bernard Maciejowski (1548-1608) by Anonymous from Kraków, ca. 1606, Franciscan Monastery in Kraków. The Primate was depicted holding silver legate's cross against silver altar set commissioned by him before 1601 in Italy and with a 15th century jewelled mitre of cardinal Frederick Jagiellon.

Reliquary of Saint Stanislaus founded by Bishop Marcin Szyszkowski by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1616-1621, Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Silver altar cross offered by Primate Wacław Leszczyński to the Gniezno Cathedral by Anonymous from Poland, first quarter of the 17th century, Archdiocesan Museum in Gniezno.

Gold chalice founded by Anna Alojza Chodkiewicz by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1633, Treasury of the Lublin Archcathedral.

Fragment of a monstrance adorned with jewels from private donations by Anonymous from Lublin, ca. 1650, Dominican Monastery in Lublin.

Fragment of monstrance adorned with enamel by Anonymous from Poland, 1670s, Treasury of the Jasna Góra Monastery.

Monstrance with St. Benedict and St. Scholastica from the Tyniec Abbey by Anonymous from Lesser Poland, 1679, Cathedral Treasury in Tarnów.

Ciborium adorned with mother of pearl founded by guardian Stefan Opatkowski by Anonymous from Kraków, 1700, Franciscan Monastery in Kraków.

The invasion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by neighbouring countries in the year of 1655 ended almost a century period of prosperity since the establishment of the noble republic in 1569. This war, one of the worst in country's history, and known as the Deluge (1655-1660), resulted in the loss of approximately 25% of the population in four core provinces, destruction of 188 cities and towns, 81 castles, and 136 churches. It had a profound impact on all aspects of life and future generations as well as on country's culture. Invasion and occupation by Lutherans from north and west (Sweden and Brandenburg), Calvinists from the south (Transylvania) and Orthodox from east and south (Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia) also significantly strengthened Catholics in previously multi-religious nation. The invaders were renowned for looting even marble flooring and church vestments. In 1658 Swedish troops of commander Pleitner murdered in the church in Skrwilno the local vicar, Father Walerian Cząpski for refusing to declare where he hidden "the treasure of the church".

In those circumstances, between 1655 and 1660, Zofia Magdalena Loka of Rogala coat of arms, owner of Okalewo estate and widow of Stanisław Piwo of Prawdzic coat of arms, deputy cup-bearer of Płock, hidden in the remains of the 11th century settlement in Skrwilno, her most valuable belongings. Discovered in 1961 in a shallow, approx. 50-cm excavation, were gold objects of more than 2 kg weigh, and silver objects of about 5 kg weigh. The treasure consist of the most exquist works of art including gold jewellery from the first half of the 17th century, like pendant with the figure of Fortune set with precious stones and coated with blue, white and green enamel, 6 chains including a chain set with precious stones made up of circular open work links and eight rosettes set with rubies and turquoises, 4 bracelets, two of them with clasps laid over with green, blue, or white enamel and the third coated with black enamel bearing the letters I.H.S. engraved amid the acanthus leaf motif, 16 żupan buttons of Stanisław Piwo, 5 gold and set with rubies, 5 with rock crystal, and 6 made of gilded silver. There is also a silver belt with imitation of encrusting, a silver filigree chain, a fragment of filigree gold chain with enamelled elements, 4 rings and 51 pearls. Silver tableware constitute the other part of the treasure. It includes silver lavabo set with Rogala coat of arms created by Balthasar Grill in Augsburg and commissioned by Jan Loka, starost of Borzechowo, father of Zofia, a pair of scissors for trimming candle wicks with Prawdzic coat of arms, two silver candlesticks made in Toruń and Brodnica, 12 silver spoons by Hans Nickel, William de Lassensy, Reinhold Sager and Hans Martelius, finest Toruń silversmiths of the time, and a tankard. Stanisław Piwo died on January 17, 1649 at the age of 53, hence before the invasion, and was buried in the Benedictine nuns Church in Sierpc, where his wife founded him a tomb monument in marble and alabaster depicting him kneeling before the crucified Christ. The tomb was most probably destroyed in 1655, when a Swedish troop looted the Benedictine Monsatery or in 1794 during the fire of the church. Zofia was 10 years younger then her husband and they were married for 26 years. Both Zofia nad Stanisław wer benefactors of many local churches - in 1644 Stanisław offered to the church in Sierpc a gold cloth chasuble and his wife in 1649 offered a silver plaque. In 1650, a year after death of her husband she offered a veil emboidered with gold thread for the image of Our Lady of Sierpc. She lived for few years in her large wooden manor in Okalewo and during the Deluge, she probably left for Gostynin. Nothing is known about her later years.

Gold chain set with precious stones of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Germany or Poland, ca. 1600, District Museum in Toruń.

Pendant with the figure of Fortune of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Transylvania or Poland, turn of the 16th and 17th century, District Museum in Toruń.

Bracelet with a stylized cartouche of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Poland, first quarter of the 17th century, District Museum in Toruń.

Silver lavabo set of Jan Loka, starost of Borzechowo by Balthasar Grill, 1615-1617, District Museum in Toruń.

The inventory was prepared by a special commision appointed by King John III Sobieski and formed in 1681 basing on the Parliament decission from the same year.

(Extract) Casket IV. 14. Diamond pendant with monogram S.A. [of Sigismund Augustus], under a crown set with rubies, with three additional rubies and a large pear-shaped pearl. 17. Clasp with diamond Saint Michael, set with a large ruby [?], an emerald, 6 smaller rubies, 3 pearls. 18. Diamond cross, 6 rubies, 3 emeralds. 19. Cross with 10 diamonds, 3 pearls. 21. Medallion with Venus and Mars with 2 sharp diamonds, 12 smaller diamonds, 10 rubies. 28. Pendant with letter A [of Queen Anna Jagiellon?] made from 4 rubies, round pearl. 36. Whistle in the form of a owl, 2 rubies, 2 diamonds, 2 diamond roses, 5 pearls. 37. Medallion with Leda and the swan, 8 diamonds, 3 rubies, emerald. 39. Cameo with bust of Charles V on yellow stone. 41. Medallion with the Judgement of Paris, diamonds, rubies. 50. Medallion with the Gigantomachy with a ruby in the center, 6 other rubies, 7 diamonds. 52. Clasp with King David, 2 rubies, smaller diamond, 25 diamonds, rubies, emeralds. 53. Large clasp with diamond Saint George, pearl dragon, 6 pearls, 24 other stones. 55. Gold lion, 6 rubies, 4 diamonds, emerald. Casket V. 2. Medallion with god Vulcan, 13 diamonds, small ruby, emerald. 4. Medallion with Gaius Mucius Scaevola, 5 diamonds, 4 rubies. 5. Clasp with diamond Saint George or Saint Michael with different tablets and diamond lilies. 7. Gold effigy of Charles V on stone. 9. Clasp with diamond Saint George without a horse. 11. Pendant with diamond Christogram IHS, a ruby at the top and a tablet with diamonds, 2 pearls. 13. Clasp with diamond King David, 6 emeralds, 18 rubies, 4 diamonds. 14. Gold dragon pipe with two large diamonds, smaller diamonds, rubies, emeralds, turquoises, 2 pearls. 15. Large clasp with diamond Saint Michael, 3 Indian pearls. 24. Diamond Saint George with emeralds and diamonds, 3 stones missing. 31. Whistle in the form of a Melusine with diamonds and rubies, 1 stone missing, 2 pearls. 33. Medallion with Mars and Venus, 3 rubies, 3 diamonds. 34. Medallion with Judgement of Solomon, emerald rows, 11 rubies, 8 emeralds. 35. Medallion with Deborah and Sisera, 6 diamonds, 4 rubies. 37. Medallion with Marcus Curtius, 3 diamonds, 2 rubies. 38. Medallion with Orpheus, 5 stones. Casket VI. 3. Agate medallion with a Roman face, diamond frame, 3 rubies. 4. Clasp with diamond Saint George, 3 rubies, 3 emeralds, pearls. 5. Medallion with Venus with a mirror, 7 diamonds, small ruby and a small pearl. 7. Pendant with a folded diamond rose, two ruby figures, 3 emeralds, large pearl, 43 tablets of diamonds. Casket VII. 7. Gold fan handle with 5 diamonds, 4 emeralds, 2 turquoises, 11 pearls. 8. Another fan handle, 12 diamonds, 8 rubies, 1 emerald, 16 pearls. Casket X. 3. Large pendant with elongated diamond of 22 1/4 carates, small pearl 12. 14. Largest diamond with a pearl of 27,5 carates weight, valued at 20.000 aureos, pearl 2.500 aureos. Summary of the Jewel Commission presented to the Lord Treasurer of the Crown, Year 1682 Value of all jewels of the Commonwealth in red zlotys ... 101.670

Gold medallion with Sacrifice of Isaac by Anonymous from Poland, turn of the 16th and 17th century, Treasury of the Jasna Góra Monastery.

Gold pendant with Annunciation to Mary by Anonymous from Poland, first quarter of the 17th century, Treasury of the Norbertines Convent in Kraków.

The reign of king John Albert was a period of gradual transition from gothic to renaissance art in Poland. Majority of preserved effigies of the king were most probably created posthumously, however the artists who worked for the Wawel Cathedral, beyond any doubt known the king personally.

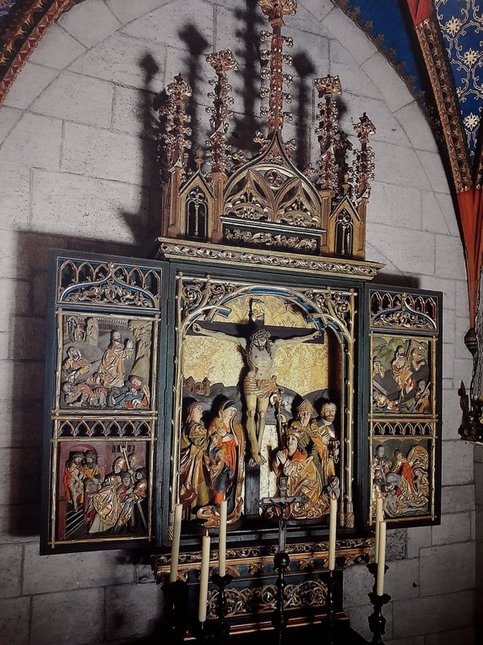

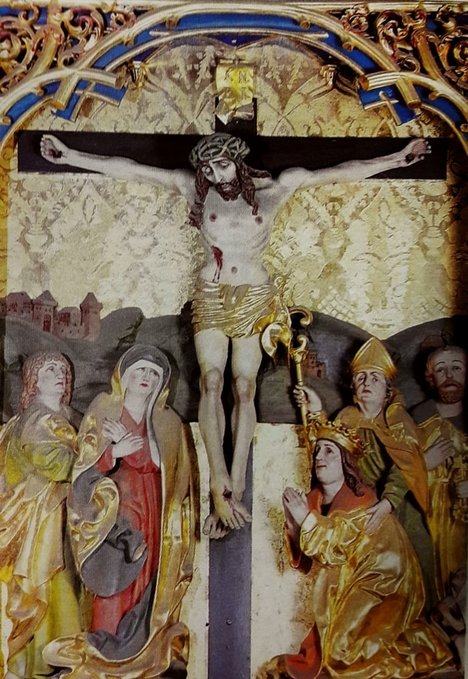

Among the oldest is a portrait of the king as a donor kneeling before the crucified Christ in a group of sculptures known as the Triptych of John Albert. The triptych was commissioned to the king's funeral chapel and created by Stanisław Stwosz (Stanislaus Stoss) in 1501. This original retable was dismanteled in about 1758 and some elements were reused in a new altar for the Czartoryski Chapel of the Cathedral between 1873 and 1884. Similar grafic effigy of the king was included in a graduale, a book collecting all the musical items of the Mass, which he founded in 1499 for the Cathedral. John Albert was depicted once again as donor, kneeling before the Apocalyptic Virgin in a miniature by Master Maciej z Drohiczyna (1484-1528). The last of the effigies, and the most important, is the king's tomb effigy carved in red marble by Jörg Huber. Late gothic image of the king lying in state with all attributes of his power was crowned between 1502 and 1505 with a renaissance arch created by Francesco Fiorentino. The tomb was founded after king's death by his mother Elizabeth of Austria and his youngest brother Sigismund.

Altar from John Albert Chapel now in the Chartoryski Chapel of the Wawel Cathedral with original sculptures from the early 16th century, in the casing from the third quarter of the 19th century by Władysław Brzostowski.

Crucifixion with king John Albert as donor by Stanisław Stwosz, 1501, Chartoryski Chapel of the Wawel Cathedral.

Crucifixion with king John Albert as donor by Stanisław Stwosz, 1501, Chartoryski Chapel of the Wawel Cathedral.

Miniature in graduale of king John Albert by Master Maciej z Drohiczyna, 1499-1501, Archives of the Wawel Metropolitan Chapter in Kraków.

Tombstone of king John Albert by Jörg Huber, ca. 1502, John Albert Chapel of the Wawel Cathedral.

The second reception stairway, the Senators' Staircase, of the Wawel Castle was constructed between 1599 and 1602 by Giovanni Trevano and Ambrogio Meazzi in the north-west corner of the castle. It is the first such modern construction in Poland facilitating the communication between the floors of the residence and located in the interior space of the edifice. Marble stairs do not run steeply, as it is in the Renaissance Deputies' Staircase, but break up regularly in the middle floors with comfortable podests. Early baroque portals of the saircase with auricular elements designed by Trevano were executed in greenish Carpathian sandstone by Meazzi. The Summary of the Royal spendings by the Kraków's supevisor Franciszek Rylski of Ostoja coat of arms from 1599 and 1600 in the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw (I 299), records a spending of fl. 2991 gr. 15 den. 12 "for demolition of the old stairs and construction of the new one, for Italians and different materials" and salaries of "Jan Treurer (Giovanni Trevano), mason ad r[ation]em fl. 1300 datum fl. 1250" and "Ambrosio Meaczi (Ambrogio Meazzi) to inlay the stairs and doors ad r[ation]em fl. 500 datum fl. 300".

Senators' Staircase of the Wawel Castle, constructed between 1599 and 1602 by Giovanni Trevano and Ambrogio Meazzi.

Bronze cartouche with coat of arms of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth without the Vasa emblem (missing) from the Wawel Castle by Anonymous from Poland, 1604, Czartoryski Museum. One of the cartouches from the overdoor in the northern wing of the castle leading to the Senators' Staircase.

See more pictures of Wawel Royal Castle during the Vasas on Pinterest - Artinpl and Artinplhub

Before 1516 the confraternity of Saint Reinhold in Gdańsk commissioned a retable for the Saint Reinhold Chapel of the Saint Mary's Church in the city. The outer wings of the polyptych were painted in the workshop of Joos van Cleve, who depicted himself as Saint Reinhold.

The polyptych was shipped to Gdańsk in 1516 and today is on display in the Gallery of Medieval Art of the National Museum in Warsaw (oak, central panel 194 × 158 cm (76.4 × 62.2 in), each wing 194 × 75 cm (76.4 × 29.5 in)). It is the first confirmed work commissioned by patrons from territories of today's Poland. The second could be Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi with a monarch in a chain of the Order of the Golden Fleece in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (oak, central panel 72 × 52 cm (28.3 × 20.5 in), each wing 69 × 22 cm (27.2 × 8.7 in)). It was acquired from the Reimer Collection in Berlin in 1843. Possibly commissioned by Sigismund I of Poland. The outer parts of the wings were painted en grisaille with effigies of Saints Christopher and Sebastian, which may indicate the donor, his patron saints, however among recipients of the Order of the Golden Fleece between 1451 and 1531 there were no Sebastian and only one Christopher - Christopher, Margrave of Baden-Hachberg (1453-1527). Although the latter was portraited in the similar headdress (crinale), he was not a king to depict himself as one of the Magi, and his facial features are completely different. Also other garments are very close to those from the known effigies of the Polish monarch - eg. Communion of Sigismund I, a leaf from the Prayer Book of Sigismund I the Old by Stanisław Samostrzelnik from 1524 in the British Library. The king of Poland was awarded the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1519 at the age of 52. The sources on artistic contacts of the Polish court at that time with the Netherlands are very scarce. Among commissions confirmed in preserved inventories and accounts there are the following. In 1526 queen Bona Sforza commissioned in Antwerp through Seweryn Boner, 16 tapestries "de lana cum figuris et imaginibus" of 200 flemish square inches in its entity. They were transported to Kraków via Frankfurt upon Main, Nuremberg and Wrocław. In 1533 king Sigismund I commissioned through Boner and Mauritius Hernyck in Antwerp 60 tapestries with coat of arms of Poland, Lithuania and Duchy of Milan among which 20 bigger with green and blue background, 26 tapestries without coat of arms and 6 tapestries with figural scenes. The commission cost was 1170 florins and tapestries were transported to Kraków via Nuremberg, Leipzig and Wrocław. In 1536 the king acquired 7 paintings in Flanders to adorn the apartments of prince Sigismund Augustus at the Wawel castle for 35 florins ("pro septem imaginibus Flandrensibus pictis"). The subtle marble bust of Queen Barbara Zapolya from Olesko Castle in the style of Netherlandish renaissance was probably part of a larger commission made by Sigismund I around 1520. Madonna and Child in architectural setting

oil on panel, ca. 1535, 33.6 × 25.2 cm (13.2 × 9.9 in), inventory number Wil.1591, Museum of King John III's Palace at Wilanów

The painting represents one of several versions of ''Madonna of the Cherries'' created by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, called Giampietrino in about 1508-1510 when he was working alongside Leonardo da Vinci. The Giampietrino's painting is possibly a reproduction of a Madonna painted by Leonardo for Francis I of France. The latter work was probably a painting that influenced Joos van Cleve who was frequently employed by French court. The painting by Giampietrino from doctor Karl Lanz's collection is a direct link to the lost da Vinci's original. The composition enjoyed great success in the early decades of the 16th century and some twenty three versions attributed to Joos van Cleve's workshop have been identified.

Similar painting is in the Arnold and Seena Davis Collection. The work was acquired by Stanisław Kostka Potocki for his collection in the Wilanów Palace in Warsaw. |

Artinpl is individual, educational project to share knowledge about works of art nowadays and in the past in Poland.

If you like this project, please support it with any amount so it could develop. © Marcin Latka Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|