|

On June 17th, 1696 died in the Wilanów Palace in Warsaw after 20 years reign, John III Sobieski, elected monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Shortly after king’s death an inventory of his belongings in the palace was opened. The document contains 122 positions of exquisite silverware, some of which could be created for 20th anniversary of king’s coronation on February 20th, 1696. In the part of royal treasury supervised by burgrave Brochocki, there was "a silver pyramid with 11 baskets made in Augsburg (No. 9.)", "a silver bowl made in Augsburg with a cover with phoenix (No. 4.)", "a three storey fountain with gilded elements made in Augsburg (No. 8.)" and "partially gilded service made in Augsburg with salt cellars, trays, vinegar cruets, bowls and Hercules in the center (No. 7.)". According to inventory the latter service had total weight of 56 grzywnas and 12 łuty, while the Kraków grzywna, used in Poland after 1650 weighed 201.86 g, therefore total weight of the service was approximately 11,304.16 g. Similar vessel from the Green Vault in Dresden (inventory number IV 292), created in 1617 in Nuremberg by Heinrich Mack and Johann Hauer, meaure 75 cm with 4686 g weight.

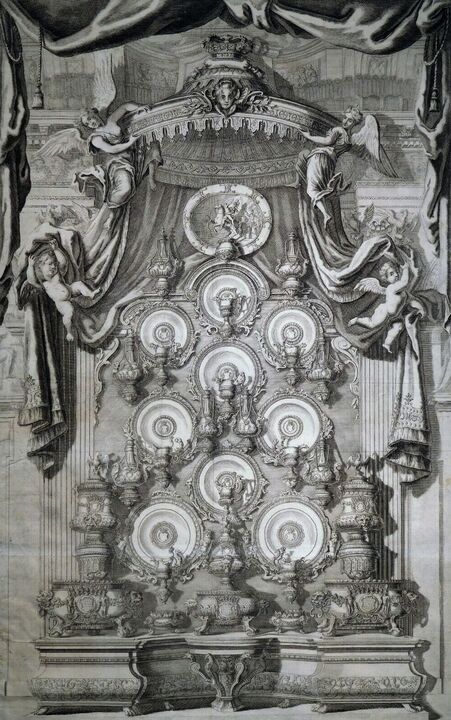

The inventory also lists some gifts from foreign monarchs including gold bowl offered by Elector of Brandenburg (till 1657 a fief of the Commonwealth as Duke of Prussia) - “gold bowl in the shape of a shell presented by Elector of Brandenburg with his coat of arms” 894 red zlotys worth, inherited by prince Aleksander Benedykt Sobieski. On March 24th, 1712 arrived to Berlin, a capital of newly created Kingdom of Prussia (earlier Brandenburg), an envoy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Saxony, count Jacob Heinrich von Flemming. His mission was to negotiate alliance against Sweden (diplomatic credentials for Flemming, Dresden March 17, 1712 [O. S. A. Rep. XI: 247 ii Fe. 55]). Both Prussia and Sweden, growing military powers in the region, pose a significant threat to the Commonwealth. Prussia claimed Courland, a vassal Duchy of the Commonwealth, Varmia and Elbląg, while Swedes were even more perilous for elected successor of John III Sobieski, Augustus II the Saxon, called the Strong, as they supported Stanislaus Leszczyński, a candidate to Commonwealth’s crown and Augustus’ rival. The king was prepared to make far-going territorial concessions to alleviate Prussia and the envoy undoubtedly has not arrived barehanded. It is possible then that Augustus has sent from Warsaw a part or whole silver service made for Sobieski, as a gift. Table centerpiece with Hercules carrying the terrestrial globe and royal eagle in the Köpenick Palace, a branch of Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin (inventory number S 559), is probably the largest and the only preserved part of the mentioned service. It measures 80 cm and bears hallmark of the city of Augsburg as well as master mark LB with a star. Stylistically the work should be attributed to Lorenz II Biller (active between 1678-1726) and dated to 1680s. The work was signed in the center of the celestial globe in Latin: Christoph Schmidt fecit Augustae 1696. Schmidt most probably modified the work by Biller’s workshop, acquired by some important patron that year, John III Sobieski. The statue also bears the date: 17 M 12 [March 1712?] at the bottom of the base on the right, possibly an inventory date. Later the centerpiece was included in the so-called great silver buffet in the Berlin City Castle. Two similar vessels are visible in the drawing from the end of the 18th century, depicting the composition of the silver buffet in about 1763 and are not visible in original composition of the buffet by Johann Friedrich Eosander from 1708. The centerpiece was therefore included in the composition between 1708 and 1763, which makes Polish provenience even more accurate.

Table centerpiece with Hercules carrying the terrestrial globe and royal eagle by Lorenz Biller II and Christoph Schmidt in Augsburg, ca. 1685 and 1696, Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

Fragment of table centerpiece with Hercules carrying the terrestrial globe and royal eagle by Lorenz Biller II and Christoph Schmidt in Augsburg, ca. 1685 and 1696, Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

Banquet given by John III Sobieski to foreign diplomats and Polish dignitaries at Jaworów on 6 July 1684 by Frans Geffels, ca. 1685, National Museum in Wrocław.

Silver buffet in the Berlin City Castle by Martin Engelbrecht, circa 1708, engraving published in Theatrum Europaeum, Volume XVI, 1717, private collection.

See the work in Polish-Lithuanian Treasures.

On November 11th, 1781 king Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski (1732-1798), the last elected monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, entered triumphally the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi, at that time part of the Polish south-eastern borderlands protection system, accompanied by prince Adam Czartoryski and voivode Józef Stępkowski. The king was greeted by general Jan de Witte, commander of the fortress.

Stanislaus Augustus arrived to Volhynia and Podolia to meet crown prince Paul of Russia (1754-1801) and his wife Natalia Alexeievna (1755-1776) who were traveling incognito as the comte et comtesse du Nord (the Count and Countess of the North) through western Europe and took this opportunity to inspect the most important fortresses. During his five-day sojourn in Kamianets the king visited the churches and the old fortress, as well as nearby Zhvanets and Khotyn. One of the most important souvenir of this travel are two portraits from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw of two Jewish women from Zhvanets. According to inscription in Polish on both of them they were commissioned by the king on November 14th, 1781 and painted by Krzysztof Radziwiłłowski - Roku 1781 dnia 14 listopada z rozkazu Najjaśniejszego pana Króla J Mości, zwiedzajacego brzegi Dniestru w Żwańcu, przedstawiona Chajka Córka kupca Abramka Lwowskim zwanego, tym portretem odmalowana przez urodzonego Krzysztofa Radziwiłłowskiego. The inscription gives the name of one of the women - Chajka (Polish spelling Hayka), the daughter of the merchant Abramek Lwowski (of Lviv). Both portraits were included in the royal collection in Warsaw as Portrait of Jewish woman Czayka (Portrait de la juive Czayka) and Portrait of Jewish woman Elia (Portrait de la juive Elia). Splendid half-length portraits of two women, one married having her hair covered and one unmarried, most probably mother and daughter, rank among the oldest preserved effigies of Jewish people from the territory of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. King’s romantic affection towards one or both women is sometimes cited as reason for creation of portraits, however there is no clear evidence of this. Although Stanislaus Augustus was famous for his short-lived romances and his chamberlain’s palace in Warsaw, the notorious Rabbit-House (Królikarnia), was described as “high-class brothel” where the king was entertained by the most beautiful women, it is also possible that he was impressed by both women or their attire, thus wanted to preserve this impression. The women wore their best clothes and jewels for so historic an occasion as king’s visit in their town. The amount of rare gold medals, pearls and other jewels, quite out of fashion at that time, worn by them was unusual for visitors from cosmopolitan capital of the Commonwealth at the end of Enlightenment. The younger woman wears a necklace made entirely of large gold medals and coins, one of which is most probably gold coronation medal of John III Sobieski and Marie Casimire from 1676 and gold earrings, while the older wears four pearl necklaces with two large gold medals, diamond earrings, diamond necklace and a bonnet adorned with pearls. Both portraits constitute an unprecedented document of great prosperity of the Jewish community in the Commonwealth shortly before it was finally dismantled by the Second and Third Partition (1793-1795).

Portrait of Chajka, Jewish woman from Zhvanets by Krzysztof Radziwiłłowski, 1781, National Museum in Warsaw.

Portrait of Elia, Jewish woman from Zhvanets by Krzysztof Radziwiłłowski, 1781, National Museum in Warsaw.

Detail of portrait of Chajka, Jewish woman from Zhvanets by Krzysztof Radziwiłłowski, 1781, National Museum in Warsaw.

Detail of portrait of Elia, Jewish woman from Zhvanets by Krzysztof Radziwiłłowski, 1781, National Museum in Warsaw. Depicted with, most likely, gold coronation medal of John III Sobieski and Marie Casimire on her necklace. Identification by Marcin Latka.

Gold coronation medal of 15 ducats worth of John III Sobieski and Marie Casimire by Johann Höhn, 1676, Private collection.

Portrait of Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski in dressing gown by Giovanni Battista Lampi, 1788-1789, National Museum in Warsaw.

At the beginning of January 1606 arrived to Kraków Jan Buczynski, secretary of tsar False Dmitry I of Russia, with the mission to acquire jewels for his patron. Several merchants from Kraków and Lviv, as well as jewellers Mikołaj Siedmiradzki and Giovanni Ambrogio Cellari from Milan, encouraged by the prospect of a large gain, embarked on a journey to Moscow.

Princess Anna Vasa (1568-1625) who owned a collection of jewels valued by some at 200,000 thalers, decided also to secretly sell to the tsar a part of it. Stanisław Niemojewski (ca. 1560-1620) of Rola coat of arms, Crown Deputy Master of the Pantry, was appointed to deliver jewels worth of 70,000 zlotys "wrapped in colourful silk" in an iron casked "painted in green". False Dmitry was killed on May 17th, 1606 and it was not as early as 1609 when the collection was returned by the new tsar Vasiliy Ivanovich Shuisky. Among jewels returned was "eagle with two diamond heads with rubies", most probably from princess' collection or pawned with Niemojewski from the State Treasury before 1599. Such hereldic jewels, either Imperial-Austrian or Polish, were undobtedly in possesion of different queens and princesses of Poland since at least 1543, when Elizabeth of Austria (1526-1545) was presented with a "diamond eagle with rubies" by emperor Charles V on the occasion of her marriage with king Sigismund II Augustus of Poland. Inventory of the jewels of Polish princess Anna Catherine Constance Vasa, daughter of Sigismund III and Constance of Austria, include four pendans and two pair of earrings with eagles, unfailingly three Imperial-Austrian and two Polish: "a pendant with a white, enamelled Eagle, at which seven diamonds, three round pearls and one big hanging ", valued at 120 thalers and "a diamond eagle with a sharply cut diamond in the center, more diamonds around and three hanging pearls". Anna Vasa, in half a princess of Poland, as a daughter of Catherine Jagiellon and sister of king Sigismund III, was as such entitled to use this emblem. After Sigismund's defeat at the Battle of Stångebro in 1598, she left Sweden to live with him in Poland where she spent the rest of her life. The miniature portrait of a lady with eagle pendant from Harrach collection in Vienna (Harrach Palace at Freyung Street) previously identified as effigy of Anna of Austria (1573-1598), first wife of king Sigismund III, basing on strong resemblance to portrait of Catherine Jagiellon, if at all connected with Poland, should be rather identified as a portrait of king’s sister Anna Vasa, and not as his wife. The lack of protruding lip, notorious "Habsburg jaw" known from Anna of Austria’s preserved portraits and costume of the sitter, according to Northern fashion and not Spanish of the Imperial court, confirms this hypothesis. Eagle was a symbol of supreme imperial power, epitomized magnanimity, the Ascension to heaven and regeneration by baptism and was used in jewellery all across Europe at that time. If the pendant is a heraldic symbol than the portrait should be dated to about 1592, when Sigismund was prepared to abandon the Polish throne for Ernest of Austria, who was about to marry princess Anna Vasa (this would also explain how the miniature found its way to Austria) or to 1598, when the princess needed to legitimize herself in her new homeland.

Diamond double-headed eagle of the House of Austria by Anonymous from Milan or Vienna, mid-16th century, Treasury of the Munich Residence. Most probably from dowry of princess Anna Catherine Constance Vasa.

Detail of a portrait of queen Anna of Austria (1573-1598) by Martin Kober, 1595, Bavarian State Painting Collections.

Miniature of princess Catherine Jagiellon (1526-1583) by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Younger, ca. 1553, Czartoryski Museum.

Miniature of a lady with eagle pendant, most probably princess Anna Vasa (1568-1625) by Anonymous, 1590s, Harrach collection in Rohrau Castle (?). Identification by Marcin Latka.

See the work in Polish-Lithuanian Treasures.

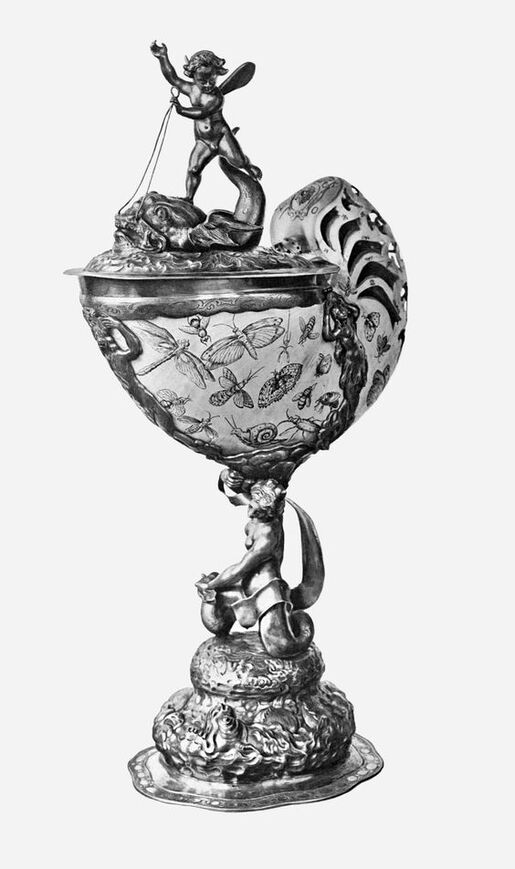

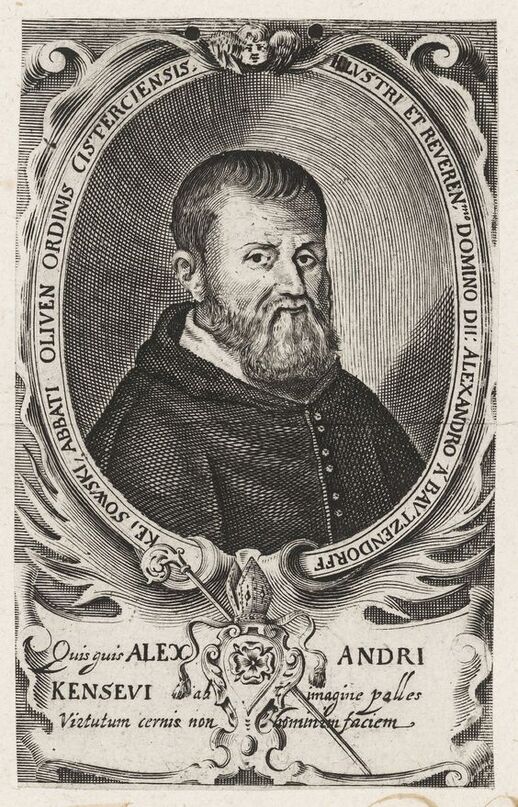

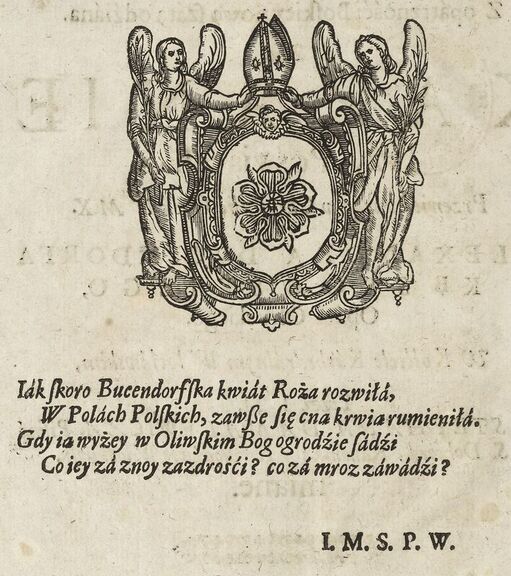

The Museum of Decorative Arts (Kunstgewerbemuseum) in Berlin prides itself on its collection of over 40 cm high nautilus cup made by the royal goldsmith Andreas I Mackensen (inventory number 1993.63). The cephalopod shell is decorated with a engraved images of insects and bats and mounted in a silver, gilt frame with sea elements - the bowl is supported by Triton, the frame is in the form of sirens and sea waves, and the cover is decorated with a putto gliding on a sea monster. At the base of the cover there is the owner's coat of arms, Aleksander Kęsowski, abbot of the Oliwa Abbey, a six-petal rose and initials A / K / A / O (ALEXANDER / KENSOWSKI / ABBAS / OLIVAE). Kęsowski, born in Kąsów in Kuyavia in 1590, became the abbot in 1641, after the death of Michał Konarski. He was a good manager and founder of many sacred buildings and a hospital of St. Lazarus in Oliwa.

The richness of the Oliwa Abbey during Kęsowski's tenure is evidenced by the account of a gift offered to King John Casimir Vasa and Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga on the occasion of their visit to Gdańsk in 1651. The abbot invited the king to dinner and during this visit he "offered to His Majesty the King the amber clock, very expensive and high, for which he gave in Gdańsk three thousand zlotys [...] to Her Majesty the Queen he offered the amber casket, very beautiful, though small", confirms the royal courtier, Jakub Michałowski, in his diary of the "Prussian Journey". "So we left Oliwa on Wednesday after dinner, accompanied along the way for some time by this abbot [Aleksander Kęsowski], who bid us farewell with good wine with a chalice in his hand" - wrote in his "Diary of travel across Europe" from 1652 Giacomo Fantuzzi, an official of the Apostolic Nunciature in Warsaw, who after seven years in Poland returned to his native Italy via Gdańsk. Earlier on, he noted in his report that here "the dining table is very important and it is very expensive, because in Poland they live sumptuously and they give expensive parties". The cup was probably made in Gdańsk and could be a gift from the king or, more likely, was ordered by the abbot himself. It is possible to set the date of its creation in the interval between 1643, when Mackensen came from Kraków to Gdańsk, and 1667, the date of Kęsowski's death. At the beginning of the 20th century it was owned by count Friedrich Schaffgotsch in Cieplice, after World War II it belonged to Udo and Mania Bey in Hamburg, and in 1993 it was acquired by the Museum of Decorative Arts from Galerie Neuse in Bremen.

Nautilus cup with coat of arms of abbot Aleksander Kęsowski by Andreas I Mackensen, 1643-1667, Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

Detail of nautilus cup with coat of arms of abbot Aleksander Kęsowski by Andreas I Mackensen, 1643-1667, Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

Detail of nautilus cup with coat of arms of abbot Aleksander Kęsowski by Andreas I Mackensen, 1643-1667, Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

Abbot Aleksander Kęsowski in Paweł Mirowski's "Kazanie na pogrzebie zacnego młodziana Jego Mości Pana Jana Bauzendorffa z Kęsowa Kęsowskiego ..." by Anonymous from Gdańsk, 1656, National Library in Warsaw.

Coat of arms of abbot Aleksander Kęsowski in Stefan Damalewicz's "Roza z opatrznośći Boskiey nową szatą odźiana, abo kazanie przy poświącaniu przewielebnego w Chrystusie Oyca, I. M. X. Alexandra Bucendorfa Kęssowskiego ..." by Cezary Franciszek in Kraków, 1642, National Library in Warsaw.

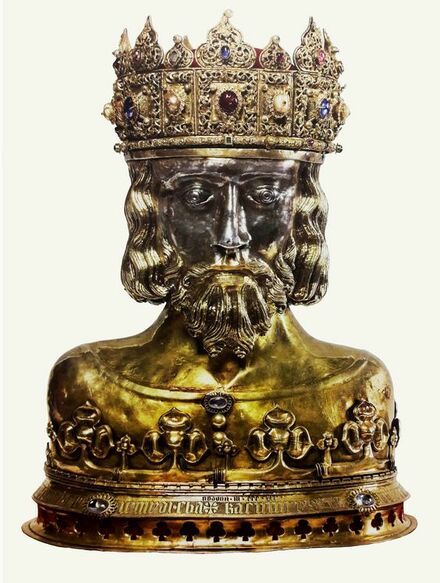

When in 1598 died queen Anna of Austria, first wife of Sigismund III Vasa, a young a chamberlain of the queen's court and governess to the king's children, Urszula Meyerin, took her position not only in the king's bed but also at the court and in country's politics. This seven-year period between first and second marriage of the king, marked by increasing role of his mistress and "a minister in a skirt" as she was called, is most probably reflected in the reliquary of Saint Ursula in the Diocesan Museum in Płock.

Before 1601 king Sigismund III ordered a goldsmith of Płock, Stanisław Zemelka, to adorn a reliquary bust of his patron Saint Sigismund in the Płock Cathedral with a gold crown from his treasury. Around the same year the king's close ally and protégé, Wojciech Baranowski, Bishop of Płock, commissioned in the workshop of royal goldsmith a silver bust for relics of Saint Ursula from the Płock Cathedral, which was to be transferred to newly established Jesuit Collegium in Pułtusk. Urszula Meyerin, a supporter of Jesuits who corresponded with the Pope and used her influence on the king to appoint her favourites to state positions, deserved the honor to give her effigy to the virgin martyr Ursula, which would be another reason for king's gratitude towards Baranowski. It is also possible that the king, himself a talented goldsmith, participated in execution of this commission, hence the lack of signature on the work.

Silver reliquary of Saint Sigismund with gold Płock Diadem by Anonymous from Kraków (reliquary) and Anonymous from Hungary or Germany (diadem), second quarter of 13th century and 1370, Diocesan Museum in Płock.

Silver reliquary of Saint Ursula in the form of a bust by Stanisław Ditrich, ca. 1600, Diocesan Museum in Płock.

In 1637, when 42-years-old king Ladislaus IV Vasa decided to marry finally, the situation at the court of his mistress Jadwiga Łuszkowska become difficult. It was probably thanks to efforts of king's wife, imperial daughter, Cecilia Renata of Austria, that Jadwiga was married to Jan Wypyski, starost of Merkinė in Lithuania and left the court in Warsaw.

Portrait of Prince Sigismund Casimir Vasa with a page (possibly illegitimate son of Łuszkowska and Ladislaus IV - Ladislaus Constantine Vasa, future Count of Wasenau) by circle of Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1647, National Gallery in Prague.

Around 1659, when the great war, known is Polish history as the Deluge, was coming to the end, it become obvious to everybody that 48-years-old queen Marie Louise Gonzaga would not give a birth to a child, everybody at the court in Warsaw were thinking on possible heir to the throne. Powerful queen gave birth to a son in 1652, but the child died after a month. The old king John Casimir Vasa, former cardinal, who finding himself unsuited to ecclesiastical life, stood in elections for the Polish throne after death of his brother and married his sister-in-law, had however at least one illegitimate child, a daughter Marie Catherine, and possibly a son.

The painting offered by queen Marie Louise to the Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw in about 1667 and created by court artist around 1659, depicts the eldest son of king’s mistress Katarzyna Franciszka (Catherine Frances) Denhoffowa. 10 years old John Casimir Denhoff as young Jesus, held by childless queen Marie Louise depicted as Virgin Mary, is offering a ring to his mother in the costume of Saint Catherine. Katarzyna Franciszka Denhoffowa nee von Bessen (or von Bees) from Olesno in Silesia and her younger sister Anna Zuzanna were maids of honor of queen Cecilia Renata and stayed at the court after queen’s death. Denhoffowa become a trusted maid of a new queen and her second husband John Casimir. In 1648, she married a courtier of John Casimir, Teodor Denhoff, and a year later on June 6, 1649 she gave birth to John Casimir Denhoff, future cardinal. Godparents of the young Denhoff were none other than king and queen herself. In 1666 at the age of 17 he was made abbot of Mogiła Abbey and between 1670 and 1674 he studied canon law in Paris under protection of John Casimir Vasa.

Mystical marriage of Saint Catherine, possibly by Jan Tricius, ca. 1659, National Museum in Warsaw.

Portrait of king John II Casimir Vasa by Daniel Schultz, 1659, Royal Baths Museum in Warsaw.

Portrait of cardinal John Casimir Denhoff by circle of Giovanni Maria Morandi, after 1687, Private collection.

See more pictures of the Polish Vasas on Pinterest - Artinpl and Artinplhub

Fashion on eastern carpets and rugs has spread with Armenian settlement on Polish soil. The partition of Armenia between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Turks in 1080 resulted in the mass migration of the Armenians from their homeland, including to Ruthenia, where Lviv became their main center. In 1356, King Casimir the Great approved the religious, self-government and judicial separation of the Lviv Armenians, and in 1519 the so-called Armenian Statute, a collection of customary Armenian rights was approved by King Sigismund I.

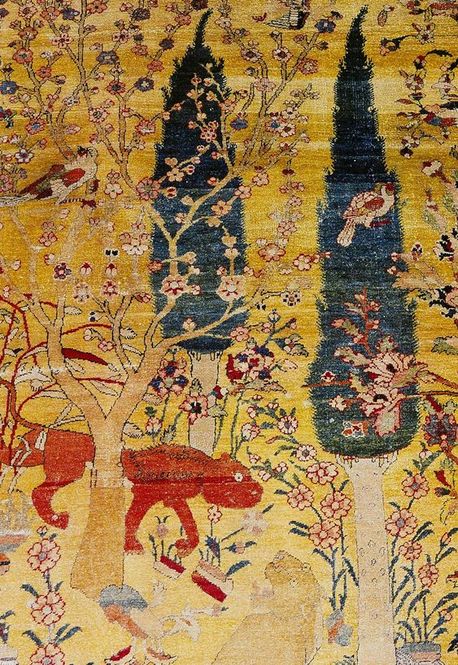

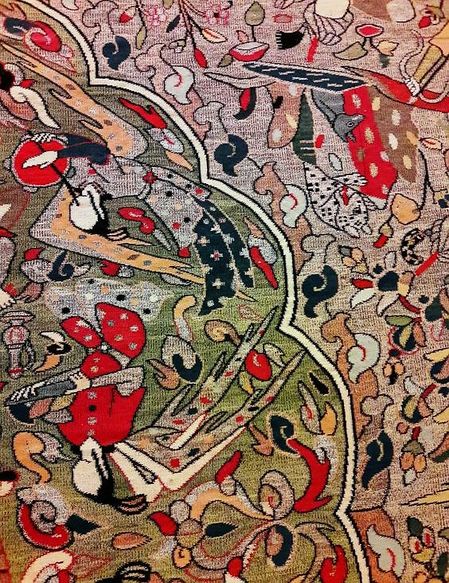

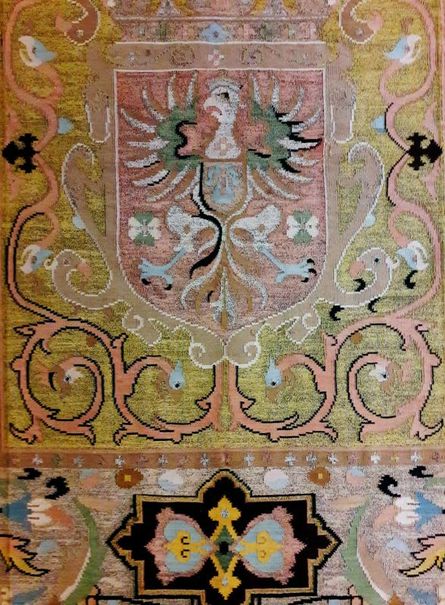

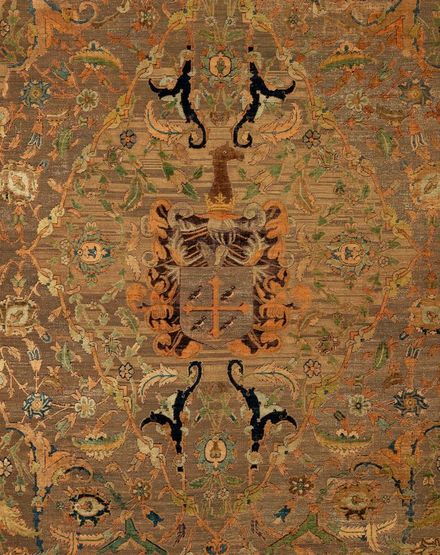

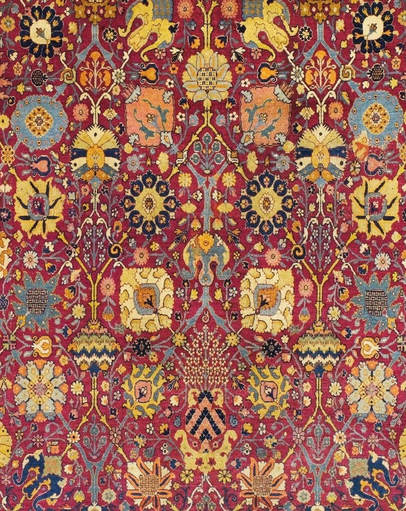

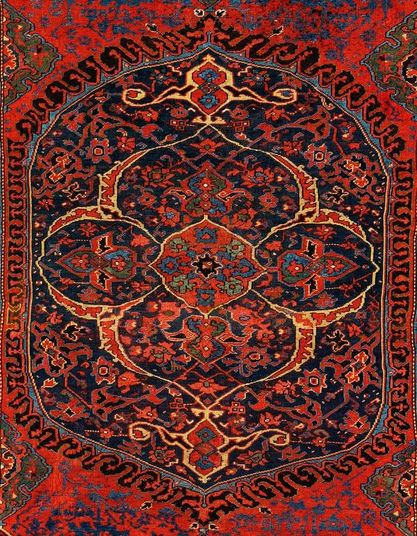

In 1533 Sigismund I sent Wawrzyniec Spytek Jordan to Turkey with the order to buy 28 carpets "for guests treating", for setting tables and "for side eating" of the King himself, besides 100 pieces of eastern fabrics "for wall covering, with flowers and border in the same color, so that they would not differ". Twenty years later, King Sigismund Augustus ordered the same Wawrzyniec Spytek to buy for himself 132 Persian carpets, some of which were intended to decorate the royal dining room. They were to have yellow flowers and "beautiful borders", the others, with an undefined pattern, were intended for the Wawel Cathedral. On April 20, 1553, he received a list of "measure of carpets ... for the need of His Highness." In 1583, in Kraków, Chancellor Jan Zamoyski bought 24 small red Turkish carpets. Persian (adziamskie) carpets were supplied by the Armenian from Caffa on the Black Sea coast who settled in Zamość, Murat Jakubowicz, who on May 24, 1585 received the royal privilege on the Chancellor's initiative to sell "Turkish" rugs in Poland for the period of 20 years. The Zamoyski Inventory from 1601 mentions the "Persian red carpets from Murat" and the "silk carpet from the Turkish tchaoush Pirali" received as a diplomatic gift. In the spring of 1601, Sigismund III Vasa, sent Sefer Muratowicz, an Armenian merchant from Warsaw who served as a royal court supplier, to Persia. "There, I ordered the carpets woven with silk and gold to be made for His Highness, and also a tent, swords from Damascus steel et caetera," wrote Muratowicz in his relation. Not only an excellent warrior, but also a talented organizer, Shah Abbas I of Persia raised the weaving industry to the highest degree. Luxury carpets become a frequent diplomatic gift, and the Shah sent legations to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1605, 1612, 1622 and 1627. In 1603 the Lviv Archbishop, Jan Zamoyski, brought twenty large carpets with Jelita coat of arms from Istanbul for the decoration of the Latin Cathedral in Lviv. In 1612, the young master Pupart donated "a Persian rug, instead of gunblades and gunpowder" to the guild of goldsmiths in Kraków and Bartosz Makuchowicz offered "white Turkish carpet". In the course of three years, between 1612 to 1614, 16 further rugs were given to the guild. The register of movables of Maria Amalia Mohylanka, daughter of Ieremia Movila, Prince of Moldavia and wife of the governor of Bratslav, Stefan Potocki, from 1612 mentions 160 silk Persian carpets "of the most diverse and of the richest eastern work". In the inventory of the Dubno Castle of Prince Janusz Ostrogski from 1616, there are about 150 Persian carpets woven with silk and gold, and the inventory of Madaliński family from Nyzhniv from 1625 mentions "Item carpets: one big and two smaller, three small, two ordinary Turkish, wall hanging varicoloured kilim, red kilim ... " White and red carpets from Persia were particularly popular. Two Persian red carpets were estimated at 20 zlotys in 1641. Before 1682, the priest from Kodeń, Mikołaj Siestrzewitowski, paid 60 zlotys for two cherry carpets. According to the order received from the court of King Ladislaus IV in Warsaw, merchant Milkon Hadziejewicz in a letter written in Lviv on October 1, 1641 to Aslangul Haragazovitch, "Armenian and merchant from the city of Anguriey" (Ankara in Turkey) commissioned him to acquire for "Her Highness the Queen", Cecilia Renata, "one rug of eighteen or twenty ells, silk woven with gold or only silk, it should be a Khorasan rug, so good and so large". According to account by Frenchman Jean Le Laboureur accompanying Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga in her journey to Poland in 1646 on the furnishings of the Warsaw Castle, "furniture is very expensive there, and royal tapestries are the most beautiful not only in Europe, but also in Asia." While Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga herself, writing from Gdańsk to Cardinal Mazarin on February 15, 1646, stated: "You will be surprised sir, that I have never seen in the French crown as beautiful tapestries as here." In the church in Oliwa, according to her account, there were 160 different rugs and tapestries. The act of compromise from 1650 between Warterysowicz and Seferowicz, the Armenian merchants in Lviv, lists in their warehouse 12 large "gold with silk" and 12 small Persian carpets, valued at 15,000 zlotys. Ożga, starost of Terebovlia and Stryi, owned 288 rugs of different pattern and origin: Persian, floor rugs, kilims, silk with letters, eagles, etc. The will of Stanisław Koniecpolski, castellan of Kraków, in 1682 (not to be confused with the hetman, died in 1646) lists two carpets, woven with gold and silver. In the end of the 17th century in Kraków, the varicoloured kilims were valued at 8 zlotys, white and red 10 zlotys, and floral and ornamental at 15 zlotys. In Warsaw in 1696 Turkish kilim was valued at 12 zlotys, the old one at 4 zlotys. Stall keeper Majowicz purchased a Turkish kilim for 15 zlotys. In Poznań, red kilims costed 6 zlotys each, and ordinary were for 3 zlotys in 1696. Armenians settled in Poland, not only traded in textiles, but also participated in the production of carpets. In Zamość, Murat Jakubowicz organized the first manufacture of eastern carpets in Poland. The imitation of Persian patterns was continued in the workshop of Manuel from Corfu, called Korfiński in Brody under the patronage of hetman Stanisław Konicepolski. The register of belongings of Aleksandra Wiesiołowska from 1659, lists 24 eastern carpets and "locally produced large carpets modelled on floor rugs 24". Although traditionally the majority of Persian and Turkish rugs in Poland, or those associated with Poland, are identified as a token of the glorious victory of the Commonwealth, which saved Europe from the Ottoman Empire invasion at the gates of Vienna in 1683, it is more likely that they were acquired in customary trading relations. When in 1878 at the Paris exhibition, Prince Władysław Czartoryski organized the "Polish Hall", presenting, among others, seven eastern carpets from his collection bearing heraldic emblems, they gained the name "Polish."

Detail of so-called Kraków-Paris carpet by Anonymous from Tebriz, second quarter of the 16th century, Wawel Royal Castle. According to tradition won at Vienna in 1683 by Wawrzyniec Wodzicki.

Detail of rug "with animals" by Herat or Tebriz manufacture, mid-16th century, Czartoryski Museum.

Detail of carpet with hunting scenes by Kashan workshop, before 1602, Residence Museum in Munich. Most probably a gift to Sigismund III Vasa from Abbas I of Persia. From dowry of Anna Catherine Constance Vasa.

Detail of Safavid kilim with the coat of arms of Sigismund III Vasa (Polish Eagle with Vasa sheaf) by Kashan workshop, ca. 1602, Residence Museum in Munich. Commissioned by the King through his agent in Persia, Sefer Muratowicz.

Mechti Kuli Beg, Ambassador of Persia, detail of Entry of the wedding procession of Sigismund III Vasa into Cracow by Balthasar Gebhardt, ca. 1605, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Krzysztof Zbaraski, Master of the Stables of the Crown in delia coat made from Turkish fabric by Anonymous, 1620s, Lviv National Art Gallery. Zbaraski served as Commonwealth's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1622 to 1624.

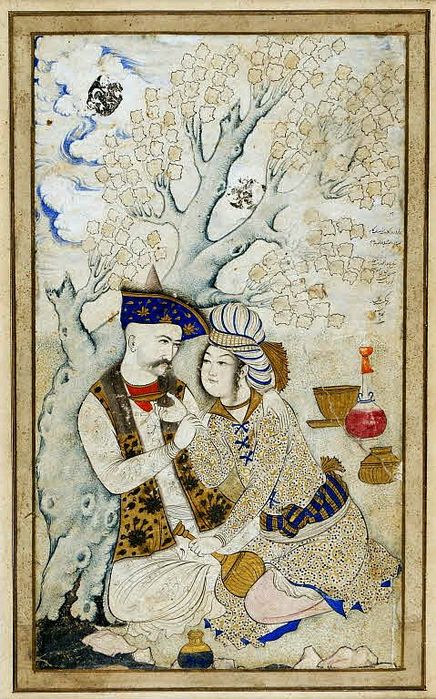

Portrait of Shah Abbas flirting with a wine boy and a couplet "May life bring you all you desire of three lips: the lip of your lover, the lip of the stream, and the lip of the cup", miniature by Muhammad Qasim, February 10, 1627, Louvre Museum.

Portrait of Stanisław Tęczyński by Tommaso Dolabella, 1633-1634, National Museum in Warsaw, deposit at the Wawel Royal Castle.

Detail of Ushak carpet with coat of arms of Krzysztof Wiesiołowski by Anonymous from Poland or Turkey, ca. 1635, Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

Portrait of a lady (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Portrait of a man (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Portrait of a young man with the view of Gdańsk (possibly member of the Węsierski family) by Peter Danckerts de Rij, ca. 1640, National Museum in Gdańsk.

Meletios I Pantogalos, metropolitan of Ephesus, during his visit to Gdańsk by Stephan de Praet and Willem Hondius, 1645, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Detail of so-called Czartoryski carpet with emblem of the Myszkowski family of the Jastrzębiec coat of arms by Anonymous from Iran, mid-17th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Possibly commissioned by Franciszek Myszkowski, castellan of Belz and marshal of Crown Tribunal in 1668 (identification of the emblem by Marcin Latka).

Lamentation of various people over the dead credit with Armenian merchant in the center by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1655, Library of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Portrait of Maksymilian Franciszek Ossoliński and his sons by Anonymous Painter from Masovia, 1670s, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Zbigniew Ossoliński by Anonymous from Poland, 1675, Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius by Daniel Schultz, 1677, Gdańsk Library of Polish Academy of Sciences.

Portrait of Kyprian Zochovskyj, Metropolitan of Kiev by Anonymous, ca. 1680, National Arts Museum of the Republic of Belarus.

Detail of vase carpet from the church in Jeziorak by Anonymous from Persia (Kirman), 17th century, Private collection.

Portrait of John III Sobieski with his son Jakub Ludwik by Jan Tricius after Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter, ca. 1690, Palace of Versailles.

Detail of medallion Ushak carpet by Anonymous from Turkey, mid-17th century, Jagiellonian University Museum. Offered by King John III Sobieski to the Kraków Academy.

Two marble lions at the main gate of the Drottningholm Palace in Sweden, credited by some sources as possibly taken by the Swedish forces from the Frederiksborg Castle in Denmark, could be rather, beyond any doubt, identifed with four marble lions described by Adam Jarzębski in his "Short Description of Warsaw" from 1643, as adorning the entrance to the Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw - I lwy cztery generalne, Między nimi, naturalne, Właśnie żywe wyrobione, A z marmuru są zrobione; Nie odlewane to rzeczy, Mistrzowską robotą grzeczy (2273-2278).

In the 1630s, before his wedding with Cecilia Renata of Austria, Ladislaus IV Vasa made several commissions for sculptures in Florence, including possibly lions for his palace in Ujazdów. Both material, Italian marble, and a form similar to Medici lions, makes this assumption more probable. Also quarterly divided fields of lions' escutcheons with wiped away crests, suggest an eagle and a knight of Poland-Lithuania, rather than more complex emblems of Christian IV of Denmark.

Marble lion from the Ujazdów Castle by Anonymous from Italy, 1630s, Drottningholm Palace. Photo: Nationalmuseum (CC BY-SA).

Marble lion from the Ujazdów Castle by Anonymous from Italy, 1630s, Drottningholm Palace. Photo: Nationalmuseum (CC BY-SA).

Main religious centers of Poland were also main centers for religious craftemanship in the country. Kraków with its status of coronation city and largest city of southern Poland had an adantage over other locations with the largest number of goldsmiths. A diploma issued in 1478 by Jan Rzeszowski, Bishop of Kraków, Jakub Dembiński, castellan and starost of Kraków, Zejfreth, mayor of Kraków, Karniowski and Jan Theschnar, Kraków's concillors to Jan Gloger, son of Mikołaj Gloger, aurifaber (goldsmith) of Kraków, recognizes Jan as a man of good fame and worthy of admission to the guild of goldsmiths. The document confirms that church had a profound influence on development of this craftsmanship in the country.

Reliquary cross of Andrzej Nosek of Rawicz coat of arms, Abbot of the Tyniec Abbey by Anonymous from Kraków, ca. 1480, Cathedral Treasury in Tarnów.

Fragment of gold reliquary for the head of Saint Stanislaus with selling of a village by Marcin Marciniec, 1504, Cathedral Museum at Wawel Hill in Kraków.

Silver crosier of Bishop Andrzej Krzycki by Anonymous from Kraków, 1527-1535, Płock Cathedral.

Portrait of Primate Bernard Maciejowski (1548-1608) by Anonymous from Kraków, ca. 1606, Franciscan Monastery in Kraków. The Primate was depicted holding silver legate's cross against silver altar set commissioned by him before 1601 in Italy and with a 15th century jewelled mitre of cardinal Frederick Jagiellon.

Reliquary of Saint Stanislaus founded by Bishop Marcin Szyszkowski by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1616-1621, Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Silver altar cross offered by Primate Wacław Leszczyński to the Gniezno Cathedral by Anonymous from Poland, first quarter of the 17th century, Archdiocesan Museum in Gniezno.

Gold chalice founded by Anna Alojza Chodkiewicz by Anonymous from Poland, ca. 1633, Treasury of the Lublin Archcathedral.

Fragment of a monstrance adorned with jewels from private donations by Anonymous from Lublin, ca. 1650, Dominican Monastery in Lublin.

Fragment of monstrance adorned with enamel by Anonymous from Poland, 1670s, Treasury of the Jasna Góra Monastery.

Monstrance with St. Benedict and St. Scholastica from the Tyniec Abbey by Anonymous from Lesser Poland, 1679, Cathedral Treasury in Tarnów.

Ciborium adorned with mother of pearl founded by guardian Stefan Opatkowski by Anonymous from Kraków, 1700, Franciscan Monastery in Kraków.

The invasion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by neighbouring countries in the year of 1655 ended almost a century period of prosperity since the establishment of the noble republic in 1569. This war, one of the worst in country's history, and known as the Deluge (1655-1660), resulted in the loss of approximately 25% of the population in four core provinces, destruction of 188 cities and towns, 81 castles, and 136 churches. It had a profound impact on all aspects of life and future generations as well as on country's culture. Invasion and occupation by Lutherans from north and west (Sweden and Brandenburg), Calvinists from the south (Transylvania) and Orthodox from east and south (Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia) also significantly strengthened Catholics in previously multi-religious nation. The invaders were renowned for looting even marble flooring and church vestments. In 1658 Swedish troops of commander Pleitner murdered in the church in Skrwilno the local vicar, Father Walerian Cząpski for refusing to declare where he hidden "the treasure of the church".

In those circumstances, between 1655 and 1660, Zofia Magdalena Loka of Rogala coat of arms, owner of Okalewo estate and widow of Stanisław Piwo of Prawdzic coat of arms, deputy cup-bearer of Płock, hidden in the remains of the 11th century settlement in Skrwilno, her most valuable belongings. Discovered in 1961 in a shallow, approx. 50-cm excavation, were gold objects of more than 2 kg weigh, and silver objects of about 5 kg weigh. The treasure consist of the most exquist works of art including gold jewellery from the first half of the 17th century, like pendant with the figure of Fortune set with precious stones and coated with blue, white and green enamel, 6 chains including a chain set with precious stones made up of circular open work links and eight rosettes set with rubies and turquoises, 4 bracelets, two of them with clasps laid over with green, blue, or white enamel and the third coated with black enamel bearing the letters I.H.S. engraved amid the acanthus leaf motif, 16 żupan buttons of Stanisław Piwo, 5 gold and set with rubies, 5 with rock crystal, and 6 made of gilded silver. There is also a silver belt with imitation of encrusting, a silver filigree chain, a fragment of filigree gold chain with enamelled elements, 4 rings and 51 pearls. Silver tableware constitute the other part of the treasure. It includes silver lavabo set with Rogala coat of arms created by Balthasar Grill in Augsburg and commissioned by Jan Loka, starost of Borzechowo, father of Zofia, a pair of scissors for trimming candle wicks with Prawdzic coat of arms, two silver candlesticks made in Toruń and Brodnica, 12 silver spoons by Hans Nickel, William de Lassensy, Reinhold Sager and Hans Martelius, finest Toruń silversmiths of the time, and a tankard. Stanisław Piwo died on January 17, 1649 at the age of 53, hence before the invasion, and was buried in the Benedictine nuns Church in Sierpc, where his wife founded him a tomb monument in marble and alabaster depicting him kneeling before the crucified Christ. The tomb was most probably destroyed in 1655, when a Swedish troop looted the Benedictine Monsatery or in 1794 during the fire of the church. Zofia was 10 years younger then her husband and they were married for 26 years. Both Zofia nad Stanisław wer benefactors of many local churches - in 1644 Stanisław offered to the church in Sierpc a gold cloth chasuble and his wife in 1649 offered a silver plaque. In 1650, a year after death of her husband she offered a veil emboidered with gold thread for the image of Our Lady of Sierpc. She lived for few years in her large wooden manor in Okalewo and during the Deluge, she probably left for Gostynin. Nothing is known about her later years.

Gold chain set with precious stones of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Germany or Poland, ca. 1600, District Museum in Toruń.

Pendant with the figure of Fortune of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Transylvania or Poland, turn of the 16th and 17th century, District Museum in Toruń.

Bracelet with a stylized cartouche of Zofia Magdalena Loka by Anonymous from Poland, first quarter of the 17th century, District Museum in Toruń.

Silver lavabo set of Jan Loka, starost of Borzechowo by Balthasar Grill, 1615-1617, District Museum in Toruń.

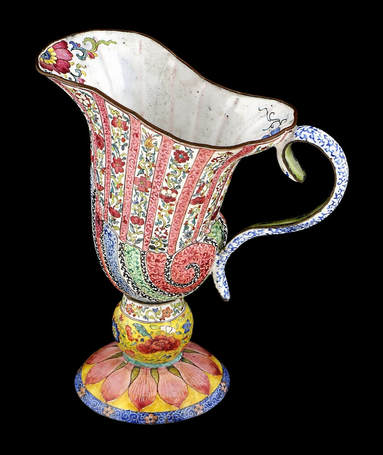

According to Franciszek Maksymilian Sobieszczański's "Historical Information on Fine Arts in Poland", Volume II from 1849, the local museum in Brno in todays Czechia, had in its collection "a beautiful basin with an ewer, all enamelled in flower stripes, which was given by John III, among other items after relief of Vienna, to Emperor Leopold I, later in Empress Maria Theresa's study, given by her to the Princes of Solm, and few years ago offered to the Moravian Museum, is today kept in Brünn with athentic documents of its provenence" (page 326). The basin from original lavabo set was most probably lost, while enamelled picher in flower stripes is in the collection of Moravian Gallery in Brno (inventory number U 24136). Despite being dated to the second half of the 17th century on the museum website, it was most probably created during Yongzheng Period (1723-1735) for Persian or Ottoman market, hence any connection with John III Sobieski (1629-1696) of Poland can be excluded.

Enamelled pitcher by Anonymous from China, Yongzheng Period (1723-1735), Moravian Gallery in Brno.

Ewer and shell-shaped basin by Anonymous from China, Yongzheng Period (1723-1735), Étude de Maigret.

|

Artinpl is individual, educational project to share knowledge about works of art nowadays and in the past in Poland.

If you like this project, please support it with any amount so it could develop. © Marcin Latka Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|