|

Portraits of Simonetta Vespucci, Beatrice d'Aragona and Barbara Zapolya as Venus and as Madonna

Around 850 the church of Santa Maria Nova (New St Mary), was built on the ruins of the Temple of Venus and Roma between the eastern edge of the Forum Romanum and the Colosseum in Rome. The temple was dedicated to the goddesses Venus Felix (Venus the Bringer of Good Fortune) and Roma Aeterna (Eternal Rome) and thought to have been the largest temple in Ancient Rome. Virgin Mary was from now on to be venerated in ancient site dedicated to the ancestor of the Roman people, as mother of Aeneas, the founder of Rome. Julius Caesar claimed Venus as his ancestor, dictator Sulla and Pompey as their protectress, she was the goddess of love, beauty, desire, sex, fertility, prosperity, and victory.

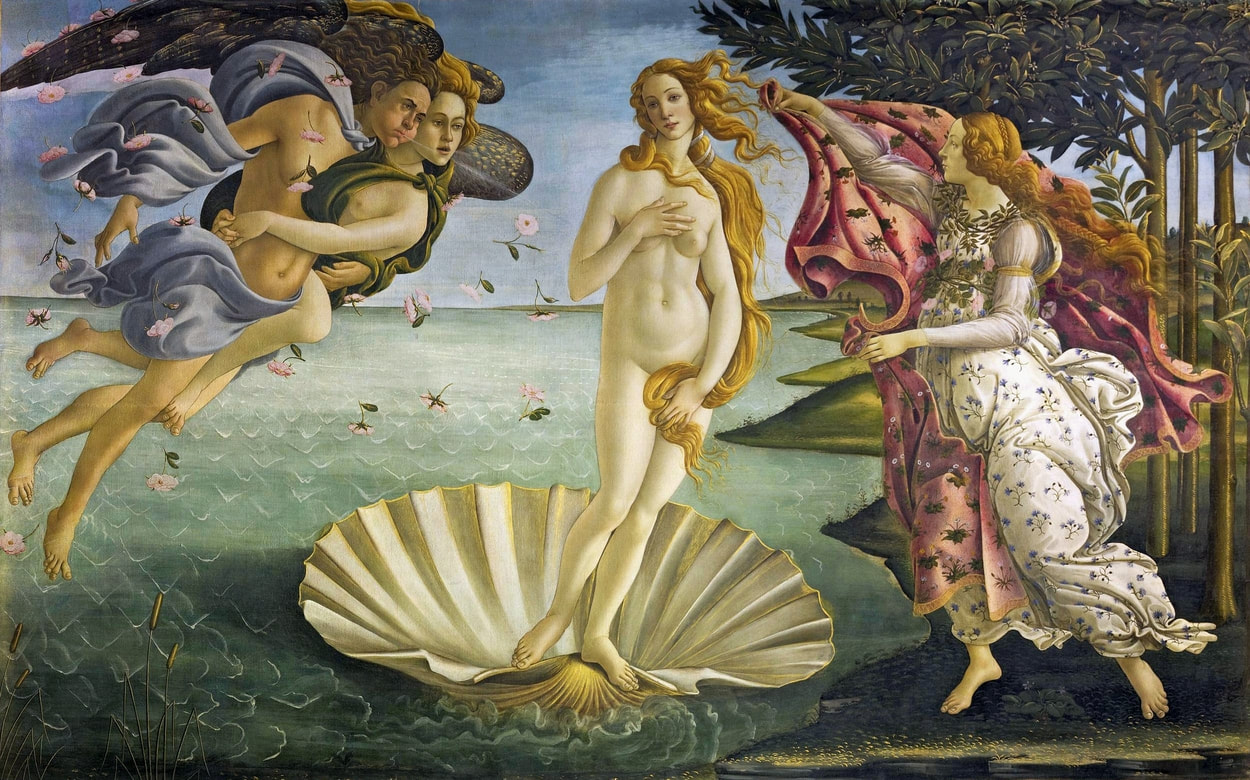

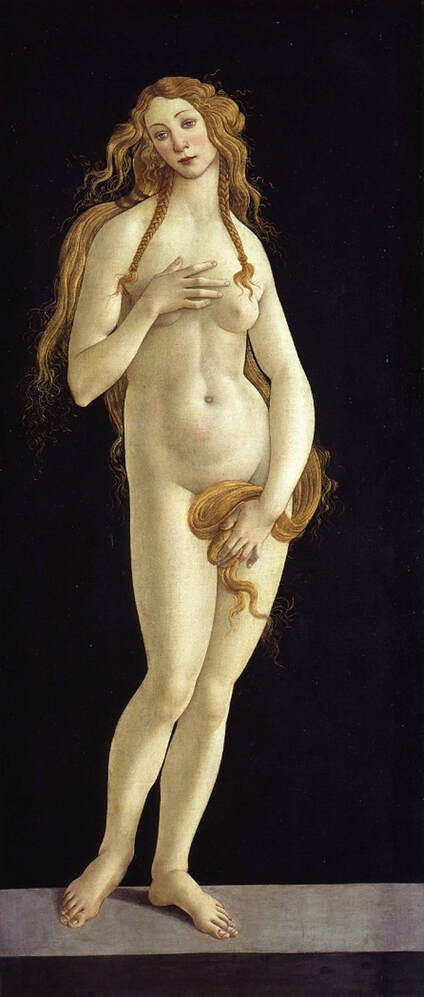

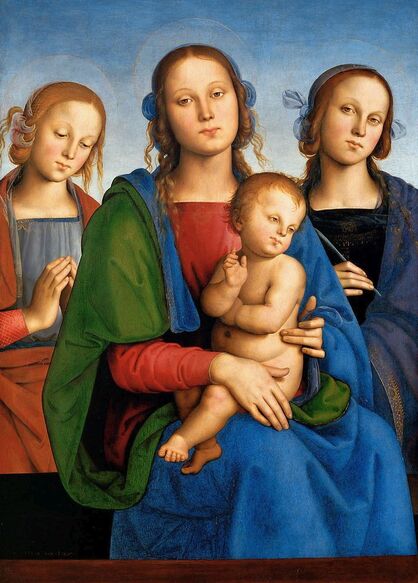

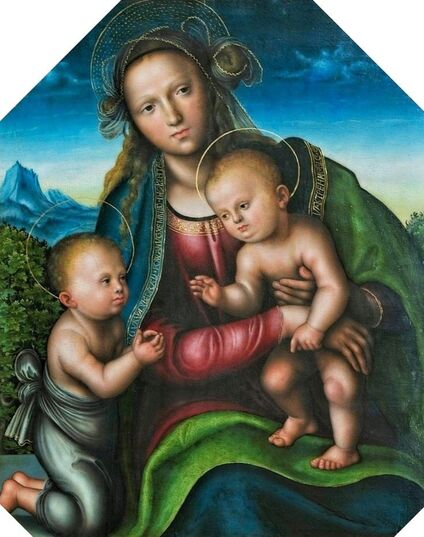

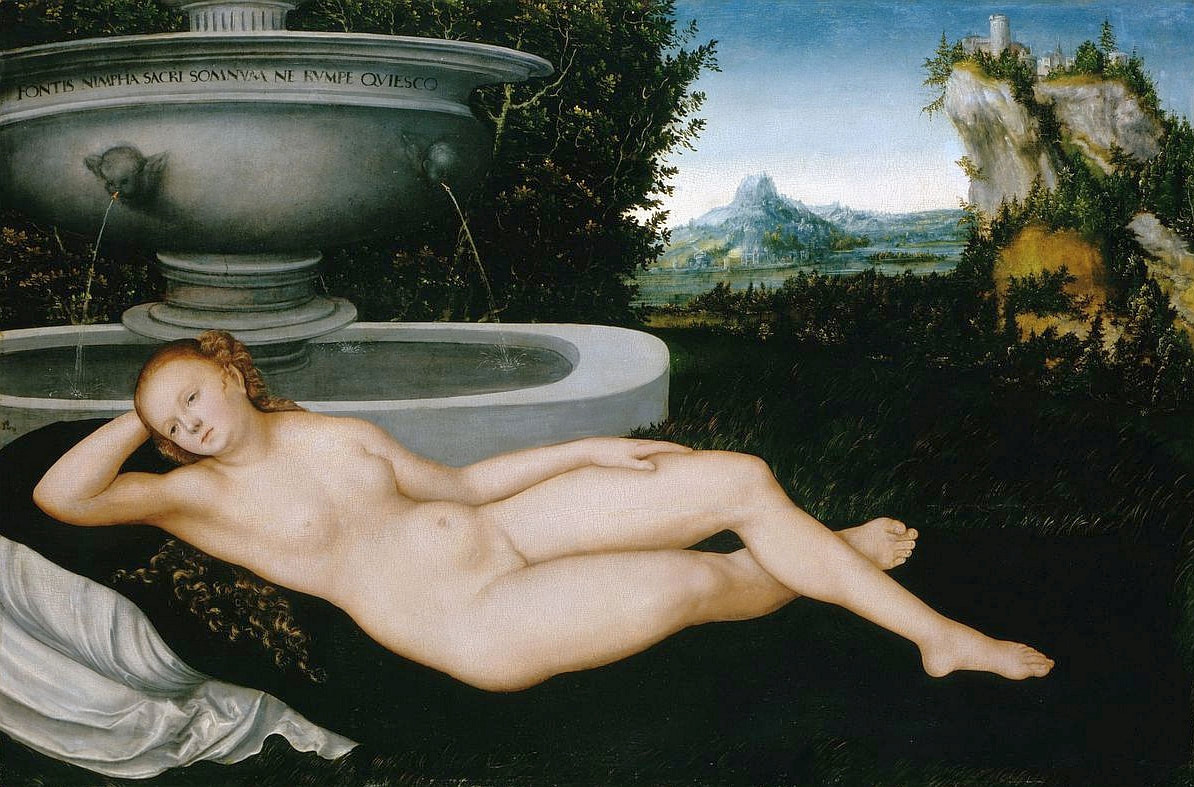

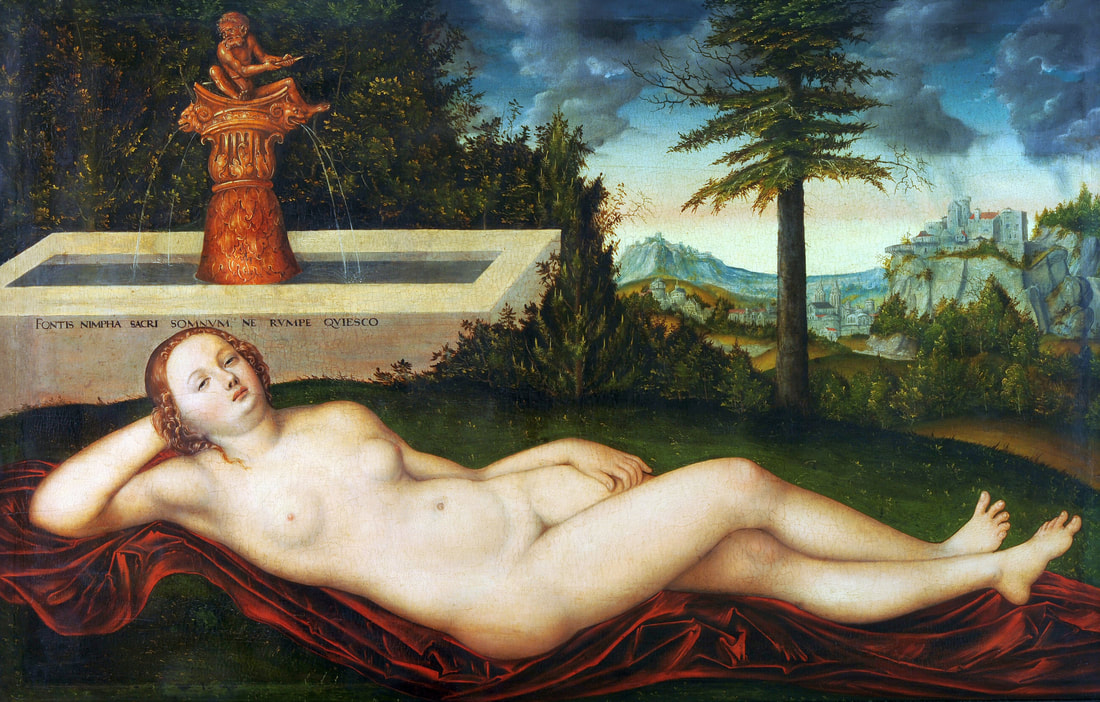

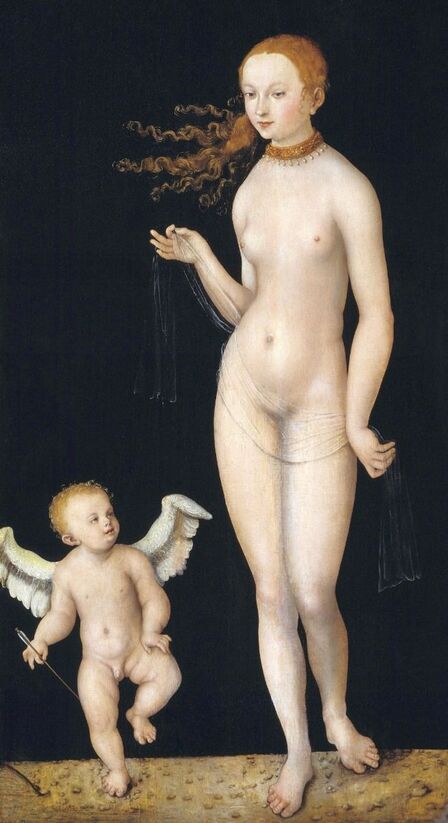

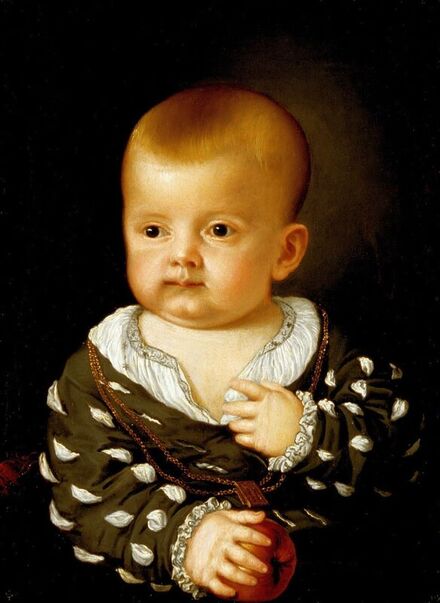

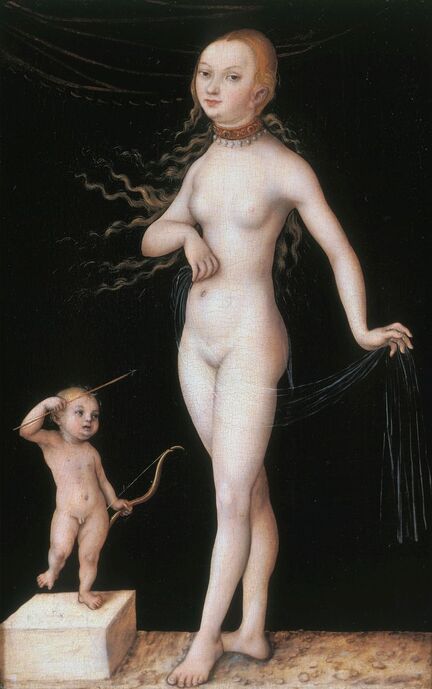

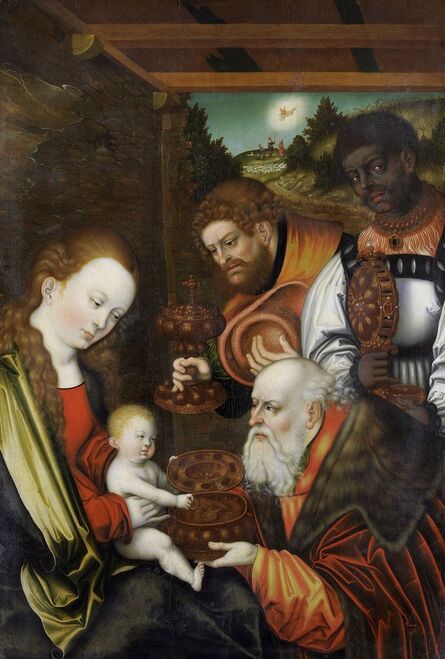

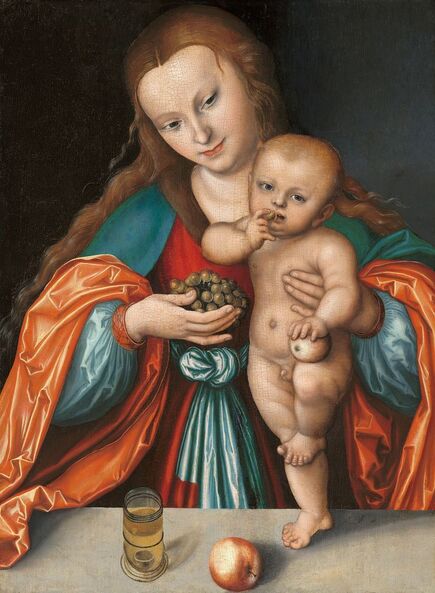

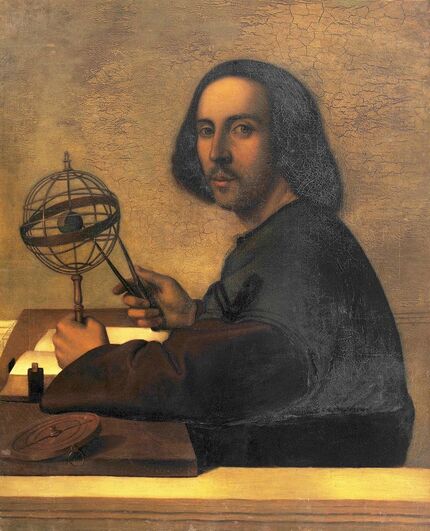

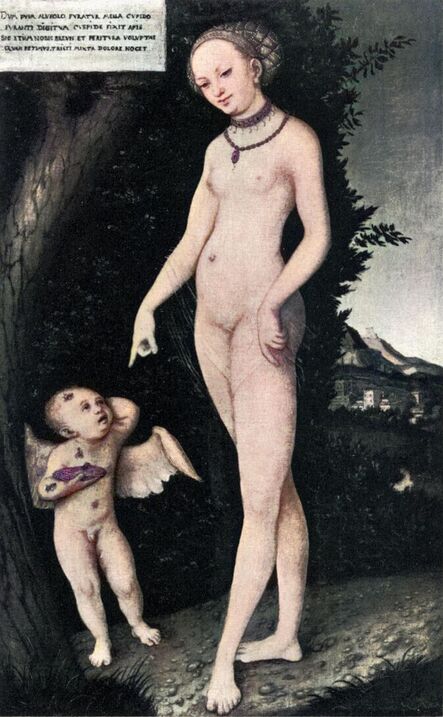

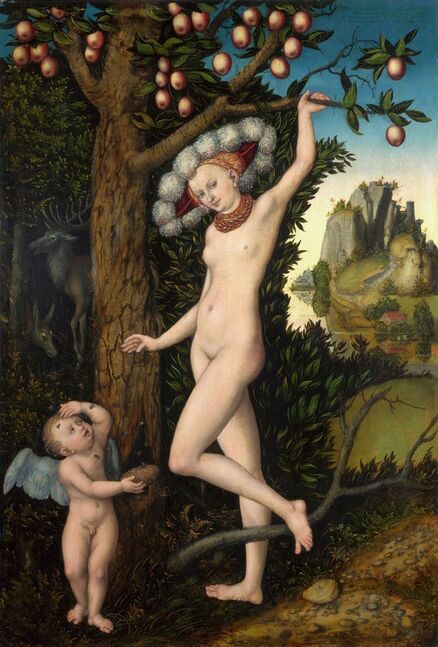

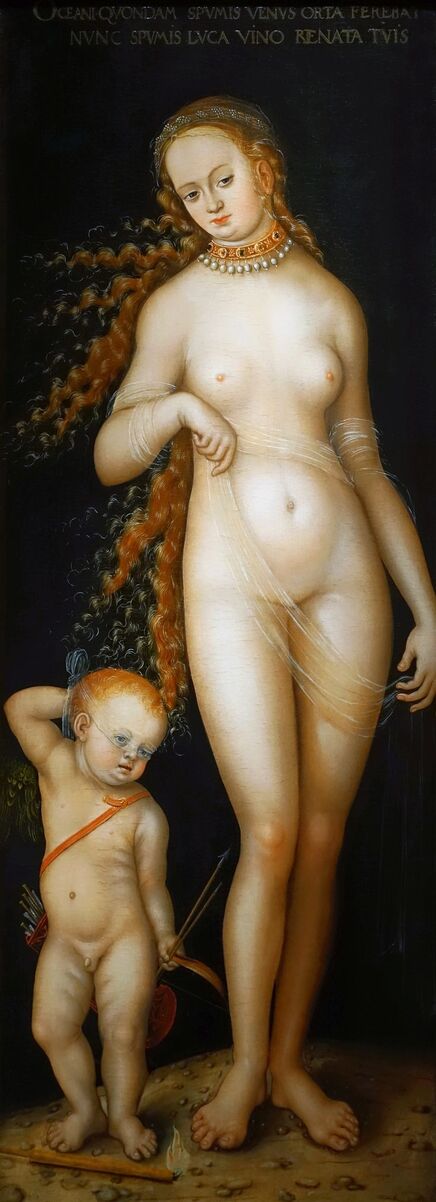

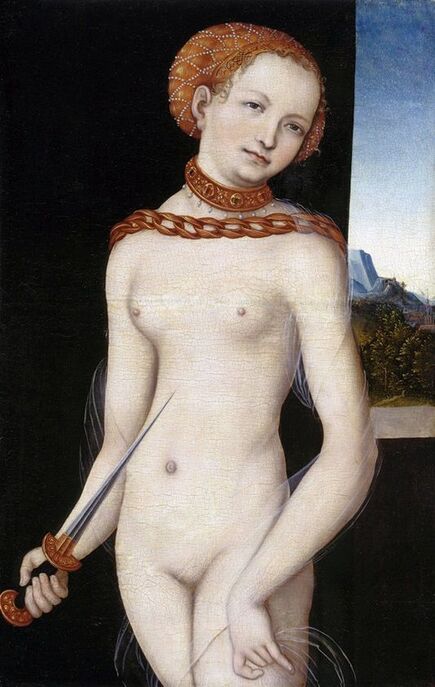

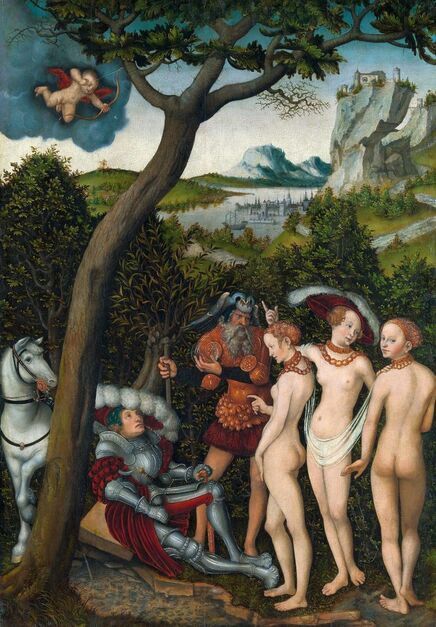

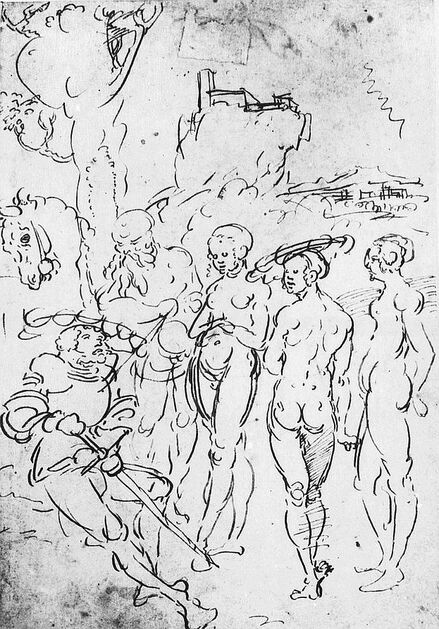

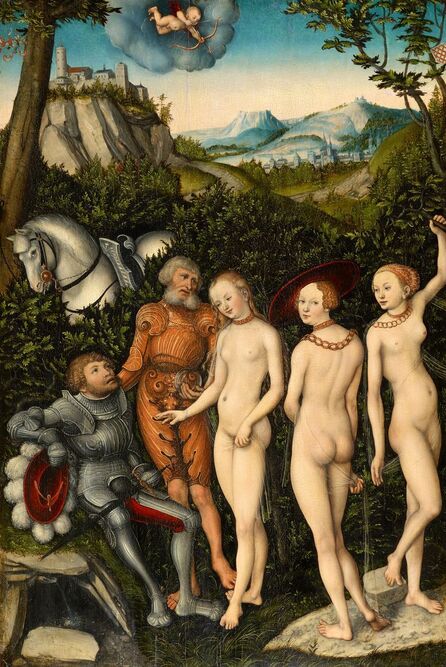

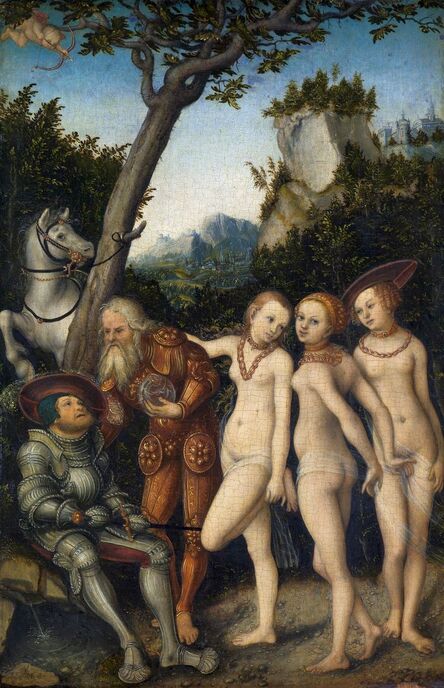

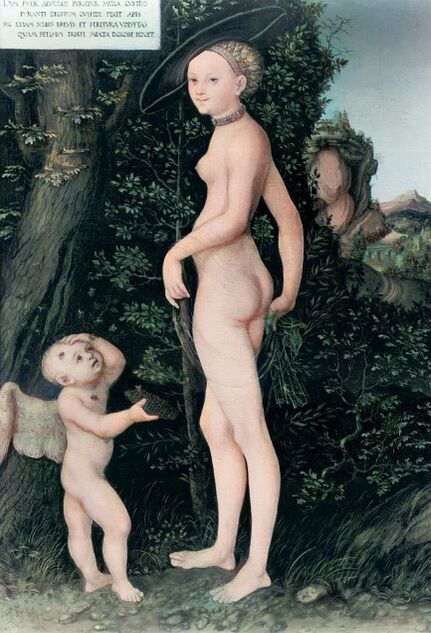

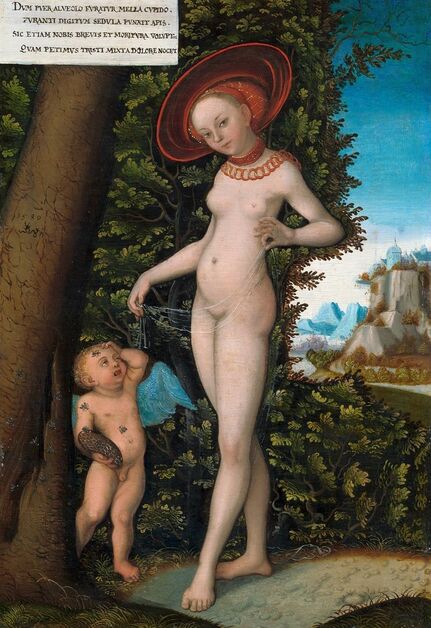

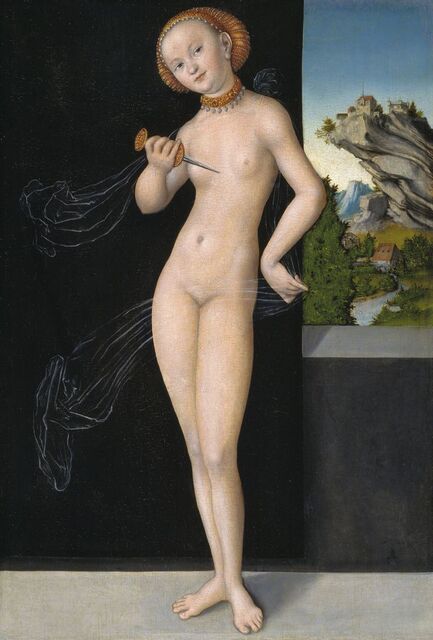

In April 1469, at age of sixteen, a Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo (1453-1476), married in Genoa in the presence of the Doge and all the city's aristocracy Marco Vespucci from the Republic of Florence, a distant cousin of the navigator Amerigo Vespucci. After the wedding, the couple settled in Florence. Simonetta quickly became popular at the Florentine court, and attracted the interest of the Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano. When in 1475 Giuliano won a jousting tournament after bearing a banner upon which was a picture of Simonetta as a helmeted Pallas Athene, painted by Sandro Botticelli, beneath which was the French inscription La Sans Pareille, meaning "The Unparalleled One", and he nominated Simonetta as "The Queen of Beauty" at that event, her reputation as an exceptional beauty further increased. She died just one year later on the night of 26/27 April 1476. On the day of her funeral she was carried through Florence in an uncovered coffin dressed in white for the people to admire her one last time and there may have existed a posthumous cult about her in Florence. She become a model for different artists and Botticelli frequently depicted her as Venus and the Virigin, the most important deities of the Renaissance, both of which had pearls and roses as their symbol. Among the best are the paintings in the National Museum in Warsaw (tempera on panel, 111 x 108 cm, M.Ob.607) and the Wawel Castle (tempera on panel, 95 cm, ZKWawel 2176) in which the Virgin has her features, as well as the goddess from the famous Birth of Venus in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence (tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, 1890 n. 878) and Venus in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (oil on canvas, 158.1 x 68.5 cm, 1124). She was also very probably the model for the Venus in the Sabauda Gallery in Turin (oil on canvas, 176 x 77.2 cm, inv. 172), purchased in 1920 by Riccardo Gualino, thus known under the name of Venus Gualino. Giorgio Vasari, recalls that similar representations, produced in Botticelli's workshop, were found in various Florentine houses. If the greatest celebrity of this era lent her appearance to the goddess of love and the Virgin, it is more than obvious that other wealthy ladies wanted to be represented similarly. On 22 December 1476 Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia married other Renaissance beauty Beatrice d'Aragona of Naples, a relative of Bona Sforza, Queen of Poland (Bona's grandfather Alfonso II of Naples was Beatrice's brother). Matthias was fascinated by his young, intelligent and well-educated wife. Her marble bust created by Francesco Laurana in the 1470s (The Frick Collection in New York, 1961.2.86) is inscribed DIVA BEATRIX ARAGONIA (Divine Beatrice of Aragon) to further enhance her remote and ethereal beauty. Numerous Italians followed Beatrice to Hungary, among them Bernardo Vespucci, brother to Amerigo, after whom America was named (after Catherine Fletcher's "The Beauty and the Terror: The Italian Renaissance and the Rise of the West", 2020, p. 36). Corvinus commissioned works of art in Florence and the painters Filippino Lippi, Attavante degli Attavanti and Andrea Mantegna worked for him. He also recived works of art from his friend Lorenzo de' Medici, like metal reliefs of the heads of Alexander the Great and Darius by Andrea da Verrocchio, as Vasari cites. It is highly possible that Venus by Sandro Botticelli or workshop in Berlin was also sent from Florence to Matthias Corvinus or brought by Beatrice to Hungary. After Corvinus' death, Beatrice married in 1491 her second husband, Vladislaus II, son of Casimir IV, King of Poland and elder brother of Sigismund I. Two paintings of Madonna and Child from the 1490s by Perugino, a painter who between 1486 and 1499 worked mostly in Florence, in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (tempera and oil on panel, 86.5 x 63 cm, GG 132, from old imperial collection) and in the Städel Museum (tempera and oil on panel, 67.7 x 51.5 cm, inv. 843, acquired in 1832) depict the same woman as the Virgin. Both effigies are very similar to Beatrice's bust by Francesco Laurana. The painting in the Städel Museum was most probably copied or re-created basing on the same set of study drawings by other artists, including young Lucas Cranach the Elder. One version, attributed to Timoteo Viti, was offered to the Collegiate Church in Opatów in 1515 by Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, who was initially Treasurer and Marshal of the Court of Prince Sigismund since 1505, and from 1515 Great Chancellor of the Crown. He was a friend of king Sigismund and frequently travelled to Hungary and Austria. Other two versions by Lucas Cranach the Elder are in private collections, including one sold in Vienna in 2022 (oil on panel, 76.6 × 59 cm, Im Kinsky, June 28, 2022, lot 95). The same woman was also depicted as Venus Pudica in a painting attributed to Lorenzo Costa in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest (oil on panel, 174 x 76 cm, inv. 1257). It was purchased by the Budapest Museum in Brescia in 1895 from Achille Glisenti, an Italian painter who also worked in Germany. Between 1498-1501 and 1502-1506 the fifth of six sons of Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon, Prince Sigismund frequently travelled to Buda, to live at the illustrous court of his elder brother King Vladislaus II. On his way there his stop was Trenčín Castle, owned by Stephen Zapolya, Palatine of the Kingdom of Hungary. Stephen was married to Polish princess Hedwig of Cieszyn of the Piast dynasty and also owned 72 other castles and towns, and drew income from Transylvanian mines. He and his family was also a frequent guest at the royal court in Buda. At the Piotrków Sejm of 1509 the lords of the Kingdom insisted on Sigismund, who was elected king in 1506, to get married and give the Crown and Lithuania a legitimate male heir. In 1509 the youngest daughter of Zapolya, Barbara, reached the age of 14 and Lucas Cranach, then Court painter to the Duke of Saxony, was despatched by the Duke to Nuremberg for the purpose of taking charge of the picture painted by Albrecht Dürer, son of a Hungarian goldsmith, for the Duke. That same year Cranach created two paintings showing the same woman as Venus and as the Virgin. The painting of Venus and Cupid, signed with initials LC and dated 1509 on the cartellino positioned against a dark background was acquired by Empress Catherine II of Russia in 1769 with the collection of Count Heinrich von Brühl in Dresden, now in the State Hermitage Museum (oil on canvas transferred from wood, 213 x 102 cm, ГЭ-680). Its prior history is unknown, therefore it cannot be excluded that Count Brühl, a Polish-Saxon statesman at the court of Saxony and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, purchased it in Poland. The painting is inspired by Botticelli and Lorenzo Costa's Venuses. However, the direct inspiration may not have been a painting but a statue, such as that of Venus and Cupid discovered near the church of Santa Croce de Gerusalemme in Rome before 1509. This large marble sculpture, now kept at the Pio Clementino Museum (214 cm, inv. 936), which is part of the Vatican Museums, was in turn inspired by Aphrodite of Cnidus (Venus Pudica) by Praxiteles of Athens. According to the inscription on the base: VENERI FELICI / SALLVSTIA / SACRVM / HELPIDVS D[onum] D[edit] (dedicated by Sallustia and Helpidus to the happy Venus), it was long believed to represent Sallustia Barbia Orbiana, a third-century Roman empress, with the title of Augusta as wife of Severus Alexander from 225 to 227 AD, represented as Venus Felix and dedicated by her liberti (freed slaves), Sallustia and Helpidius. The portrait heads are also interpreted to represent unknown Sallustia as Venus and her son Helpidus as Cupid and the origins described as possibly coming from the temple near the Horti Sallustiani (Gardens of Sallust). Nowadays, the statue is considered to be a "disguised portrait" of Empress Faustina Minor (died ca. 175 AD), wife of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (compare "The Art of Praxiteles ... " by Antonio Corso, p. 157). It resembles another disguised statue of Faustina, represented as Fortuna Obsequens, Roman goddess of indulgent fate (Casa de Pilatos in Seville) and her bust in Berlin (Altes Museum). The second painting, very similar to effigies of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna, shows this woman against the landscape which is very similar to topography of the Trenčín Castle, where Barbara Zapolya spent her childhood and where she met Sigismund. This painting, now kept at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid (oil on panel, 71.5 x 44.2 cm, 114 (1936.1)), comes from the collection of the British art critic Robert Langton Douglas (1864-1951), who lived in Italy from 1895 to 1900, and was acquired in New York in 1936. She offeres the Child a bunch of grapes a Christian symbol of the redemptive sacrifice, but also a popular Renaissance symbol for fertility borrowed from the Roman god of the grape-harvest and fertility, Bacchus. Both women resemble greatly Barbara Zapolya from her portrait with B&S monogram. In the main altar of the 13th century church in Strońsko near Sieradz in central Poland, there is very similar version of this painting by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder. The Latin inscription on Venus in Saint Petersburg warns the man for whom it was intended: "Drive out the excesses of Cupid with all your strength, so that Venus may not take over your blinded heart" (PELLE · CVPIDINEOS · TOTO / CONAMINE · LVXVS / NE · TVA · POSSIDEAT / PECTORA · CECA · VENVS).

Statue of Empress Faustina the Younger as Venus Felix, Ancient Rome, ca. 170-175 AD, Pio Clementino Museum.

Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist and an angel by Sandro Botticelli, 1470s, National Museum in Warsaw.

Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Madonna and Child with angels by Sandro Botticelli or workshop, 1470s, Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków.

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli, 1484-1485, Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Venus by Sandro Botticelli or workshop, fourth quarter of the 15th century, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

Venus by Sandro Botticelli or workshop, fourth quarter of the 15th century, Sabauda Gallery in Turin.

Portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Venus by Lorenzo Costa, fourth quarter of the 15th century, Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest.

Portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna and Child with Saints by Perugino, 1490s, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist by Perugino, 1490s, Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main.

Portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist by Timoteo Viti or Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1490s, St. Martin's Collegiate Church in Opatów.

Portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1490s, Private collection.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1509, The State Hermitage Museum.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Madonna and Child with a bunch of grapes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1509-1512, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Madonna and Child against a landscape by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1509-1512, Parish church in Strońsko.

Portrait of Magdalena Thurzo by Lucas Cranach the Elder

One of the earliest and the best of Cranach's Madonnas is in the Archdiocesan Museum in Wrocław (oil on panel, 70.3 x 56.5 cm). The work was initially in the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Wrocław and is believed to have been offered there in 1517 by John V Thurzo, Prince-Bishop of Wrocław, who also founded a new sacristy portal, considered to be the first work of the Renaissance in Silesia. Thurzo, who came from the Hungarian-Slovak-Polish-German patrician family, was born on April 16, 1464 or 1466 in Kraków, where his father built a smelter in Mogiła. He studied in Kraków and in Italy and he began his ecclesiastical career in Poland (scholastic in Gniezno and in Poznań, a canon in Kraków). Polish King John I Albert sent him on several diplomatic missions. Soon afterwards he moved to Wrocław in Silesia and become a canon and dean of the cathedral chapter in 1502 and Bishop of Wrocław from 1506.

Thurzo owned a sizable library and numerous works of art. In 1508 he paid 72 florins to Albrecht Dürer, the son of a Hungarian goldsmith, for a painting of Virgin Mary (Item jhr dörfft nach keinen kaufman trachten zu meinem Maria bildt. Den der bischoff zu Preßlau hat mir 72 fl. dafür geben. Habs wohl verkhaufft.), according to artist's letter from November 4, 1508. According to Jan Dubravius, he also owned Dürer's Adam and Eve, for which he paid 120 florins. In 1515, John's younger brother Stanislaus Thurzo, Bishop of Olomouc commissioned Lucas Cranach the Elder to create an altarpiece on the themes of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist and the Beheading of St. Catherine (Kroměříž Castle), while his other brother George, who married Anna Fugger, was portrayed by Hans Holbein the Elder (Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin). In 1509 or shortly after, he completed the reconstruction of the episcopal summer residence in Javorník. The medieval castle built by the Piast duke Bolko II of Świdnica was converted into a Renaissance palace from 1505, according to two stone plaques on the castle wall created by the workshop of Francesco Fiorentino (who later worked in Poland) in Kroměříž, one starting with the words "John Thurzo, bishop of Wroclaw, a Pole, repaired this citadel" (Johannes Thurzo, episcopus Vratislaviensis, Polonus, arcem hanc bellorum ac temporum injuriis solo aequatam suo aere restauravit, mutato nomine montem divi Joannis felicius appellari voluit M. D. V.). He also renamed the castle as John's Hill (Mons S. Joannis, Jánský Vrch, Johannisberg or Johannesberg), to honor the patron of the Bishops of Wrocław, Saint John the Baptist. In Thurzo's time, the castle became a meeting place for artists and scholars, including the canon of Toruń, Nicholas Copernicus. Together with his brother Stanislaus, the bishop of Olomouc, he crowned the three-year-old Louis Jagiellon as King of Bohemia on March 11, 1509 in Prague. Bishop Thurzo had two sisters. The younger Margaret married Konrad Krupka, a merchant from Kraków and the elder Magdalena was first married to Max Mölich from Wrocław and in 1510 she married Georg Zebart from Kraków, who were both involved in financial undertakings of her father John III Turzo in Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. The painting of the Wrocław Madonna is generally dated to about 1510 or shortly after 1508, when Cranach was ennobled by Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, because a signet ring decorated with the inverted initials 'L.C' and Cranach's serpent insignia is one of the most important items in the painting. The castle on a fantastic rock in the background with two round towers, a small inner courtyard and a gate tower on the right match perfectly the layout and the view of the Jánský Vrch Castle in the early 16th century (hypothetical reconstruction drawings by Rostislav Vojkovský). Scaffolding and a ladder are also visible, the building is clearly being rebuilt and extended. The child is holding grapes, Christian symbol of Redemption, but also an ancient symbol of fertility. The woman depicted as the Virgin bears resemblance to effigies of George Thurzo (Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid and Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin), she sould be therefore identified as Magdalena Thurzo, who around that time was about to get married.

Portrait of Magdalena Thurzo as Madonna and Child with a bunch of grapes against the idealized view of Jánský Vrch Castle by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1509-1510, Archdiocesan Museum in Wrocław.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by Lucas Cranach the Elder

"In the Christian world well through the Renaissance, males were associated with the head (and therefore with thinking, reason, and self-control) and females with the body (and therefore with senses, physicality, and the passions)" (Gail P. Streete's "The Salome Project: Salome and Her Afterlives", 2018, p. 41).

During Renaissance Salome became an erotic symbol of daring, uncontrollable female lust, dangerous female seductiveness, woman's evil nature, the power of female perversity, but also a symbol of beauty and complexity. One of the oldest representations of Dance of Salome is a fresco in the Prato Cathedral, created between 1452 and 1465 by Filippo Lippi, who also created some paintings for Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary. In April 1511, Sigismund informed his brother, King Vladislaus, that she wants to marry a Hungarian noblewoman. He chose Barbara Zapolya. The marriage treaty was signed on 2 December 1511 and Barbara's dowry was fixed at 100,000 red złotys. Barbara was praised for her virtues, Marcin Bielski wrote of her devotion to God and obedience to husband, kindheartedness and generosity. The painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder in Lisbon depict her as Salome wearing a fur-trimmed coat and a fur hat. It was offered to the Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon by Luis Augusto Ferreira de Almeida, 1st Count of Carvalhido. It is possible that the painting was sent to Portugal in the 16th century by the Polish-Lithuanian court. In 1516 Jan Amor Tarnowski, who was educated at the court of the Jagiellonian monarchs, and two other Polish lords were knighted in the church of St. John in Lisbon by King Manuel I. More than one decade later, in 1529 and again in 1531 arrived to Poland-Lithuania Damião de Góis, who was entrusted by King John III of Portugal with a mission to negotiate the marriage of Princess Hedwig Jagiellon, a daughter of Barbara Zapolya, with king's brother. In 1520, Hans Kemmer, a pupil of Lucas Cranach the Elder in Wittenberg, probably shortly after his return to his native town of Lübeck (first mentioned in the Town Book on May 25, 1520), created a copy or rather a modified version of this painting. He signed this work with a monogram HK (linked) and dated '1520' at the edge of the dish. It comes from private collection in Austria and was sold in 1994 (oil on panel, 58 x 51 cm, Dorotheum in Vienna, October 18, 1994, lot 151). Her costume is more ornate in this version, but the face is not very elaborately painted. The sitter's velvet fur-lined hat is evidently Eastern European and similar was depicted in a Portrait of a man with a fur hat by Michele Giambono (Palazzo Rosso in Genoa), created in Venice between 1432-1434, which is identified to represent a Bohemian or Hungarian prince who came to Italy for the coronation of Emperor Sigismund. Her left hand is unnatural and almost grotesque or "naively" painted (repainted in the Lisbon version most likely in the 19th century), which is an indication that the painter based on a study drawing that he received to create the painting and not seen the live model. Few years later Laura Dianti (d. 1573), mistress of Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, was depicted in several disguised portraits by Titian and his workshop. Her portrait with an African page boy (Kisters Collection at Kreuzlingen) is known from several copies and other versions, some of which depict her as Salome. The original by Titian in guise of biblical femme fatale was probably lost. Paintings of Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist by Titian and his workshop (Uffizi Gallery in Florence and Musée Fesch in Ajaccio) are also identified to depict Laura as well as Saint Mary Magdalene by circle of Titian (Private collection). They all followed the same Roman pattern of portraits in the guise of deities and mythological heroes. The image of Herodias/Salome preserved in the Augustinian monastery in Kraków and the posthumous inventory of Melchior Czyżewski, who died in Kraków in 1542, lists as many as two such paintings. The popularity of such images in Poland-Lithuania is reflected in poetry. In the fragmentarily preserved works of Mikołaj Sęp Szarzyński (ca. 1550 - ca. 1581) there are four epigrams on paintings, including "On the image of Saint Mary Magdalene" and "On the image of Herodias with the head of Saint John" (after "Od icones do ekfrazy ..." by Radosław Grześkowiak).

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1510-1515, National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya as Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by Hans Kemmer, 1520, Private collection.

Portraits of Barbara Zapolya and Barbara Jagiellon by Lucas Cranach the Elder

On November 21, 1496 in Leipzig, Barbara Jagiellon, the fourth daughter of Casimir IV Jagiellon, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania and Elizabeth of Austria, Princess of Bohemia and Hungary, that reached adulthood, married George of Saxony, son and successor of Albert III the Bold, Duke of Saxony and Sidonie of Podebrady, a daughter of George, King of Bohemia, in a glamorous and elaborate ceremony. 6,286 German and Polish nobles are said to have attended the wedding. The marriage was important for the Jagiellons because of the rivalry with the Habsburgs in Central Europe.

As early as 1488, while his father was away on campaigns in Flanders and Friesland, George, Barbara's husband, held various official duties on his behalf, and succeeded him after his death in 1500. George's cousin, prince-elector Frederick the Wise, was a very pious man and he collected many relics, including a sample of breast milk from the Blessed Virgin Mary. In 1509 the elector had printed a catalogue of this collection, produced by his court artist Lucas Cranach and his inventory of 1518 listed 17,443 items. In 1522, Emperor Charles V proposed engagement of Hedwig Jagiellon, the eldest daughter of Sigismund I, Barbara's brother, with John Frederick, heir to the Saxon throne and Frederick the Wise's nephew, as the elector most probably homosexual in relationship with Degenhart Pfäffinger, remained unmarried. The portrait of Frederick by circle of Lucas Cranach the Elder from the 1510s is in the Kórnik Castle near Poznań. On 20 November 1509 in Wolfenbüttel, Catherine (1488-1563), a daughter of the Duke Henry IV of Brunswick-Lüneburg, married Duke Magnus I of Saxe-Lauenburg (1470-1543). Soon after the wedding she bore him a son, future Francis I (1510-1581). Magnus was the first of the Dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg to renounce Electoral claims, which had long been in dispute between the two lines of the Saxon ducal house. He carried neither the electoral title nor the electoral swords (Kurschwerter) in his coat of arms. The electoral swords indicated the office as Imperial Arch-Marshal (Erzmarschall, Archimarescallus), pertaining to the privilege as prince-elector. On 12 August 1537, the eldest daughter of Catherine and Magnus, Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg (1511-1571), was crowned Queen of Denmark and Norway in the Copenhagen Cathedral. "That they may see a great kingdom and a mighty people, that they may bear their lord's queen under the stars, O happy virgin, happy stars who have borne you, for the glory of your country" (Ut videant regnum immensum populumque potentem: Reginam domini ferre sub astra sui, O felix virgo, felicia sidera, que te, Ad tantum patrie progenuere decus), wrote in his "Hymn for the Coronation of Queen Barbara" (In Augustissimu[m] Sigisimu[n]di regis Poloniae et reginae Barbarae connubiu[m]), published in Kraków in 1512, the queen's secretary Andrzej Krzycki. Queen Barbara Zapolya was crowned on 8 February 1512 in the Wawel Cathedral. She brought Sigismund a huge dowry of 100,000 red zlotys, equal to the imperial daughters. Their wedding was very expensive and cost 34,365 zlotys, financed by a wealthy Kraków banker Jan Boner. A painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder in the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen dated to about 1510-1512 shows a scene of the Mystical marriage of Saint Catherine. The Saint "as a wife should share in the life of her husband, and as Christ suffered for the redemption of mankind, the mystical spouse enters into a more intimate participation in His sufferings" (after Catholic Encyclopaedia). Virgin Mary bears features of Queen Barbara Zapolya, similar to paintings in the Parish church in Strońsko or in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. The woman on the right, depicted in a pose similar to some donor portraits, is identified as effigy of Saint Barbara. It was therefore she who commissioned the painting. Her facial features bears great resemblance to the portrait of Barbara Jagiellon by Cranach from the Silesian Museum of Fine Arts in Wrocław, today in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The effigy of Saint Catherine bears strong resemblance to the portrait of Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg, queen of Denmark and daughter of Catherine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Duchess of Saxe-Lauenburg, in the Frederiksborg Castle, near Copenhagen. Described painting comes from the Danish royal collection and before 1784 it was in the Furniture Chamber of the royal Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen. The painting bears coat of arms of the Electorate of Saxony in upper part. The message is therefore that Saxe-Lauenburg should join the "Jagiellonian family" and thanks to this union they can regain the electoral title. A good workshop copy, acquired in 1858 from the collection of a Catholic theologian Johann Baptist von Hirscher (1788-1865) in Freiburg im Breisgau, is in the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe. The painting is very similar to other Mystical marriage of Saint Catherine by Lucas Cranach the Elder, which was in the Bode Museum in Berlin before World War II, lost. In this scene Queen Barbara is most probably surrounded by her Hungarian and Moravian court ladies in guise of Saints Margaret, Catherine, Barbara and Dorothea. It was purchased from a private collection in Paris, hence the provenance from the Polish royal collection cannot be excluded - John Casimir Vasa, great-grandson of Sigismund I in 1668 and many other Polish aristocrats transferred to Paris their collections in the 17th century and later. The copy of this painting from about 1520 is in the church in Jachymov (Sankt Joachimsthal), where from 1519 Louis II, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia minted his famous gold coin, Joachim thaler. The woman in an effigy of Lucretia, a model of virtuous woman by Lucas Cranach the Elder, which was in the late 19th century in the collection of Wilhelm Lowenfeld in Munich, is very similar to the effigy of Barbara Jagiellon in Copenhagen. It is one of the earliest of the surviving versions of this subject by Cranach and is considered a pendant piece to the Salome in Lisbon (Friedländer). Both paintings have similar dimensions, composition, style, the subject of an ancient femme fatale and were created in the same period. The work in Lisbon depicts Barbara Jagiellon's sister-in-law, Queen Barbara Zapolya. Similar effigy of Lucretia, also by Cranach the Elder, was auctioned at Art Collectors Association Gallery in London in 1920. The effigy of the Virgin of Sorrows in the National Gallery in Prague, which was donated in 1885 by Baron Vojtech (Adalbert) Lanna (1836-1909), is almost identical with the face of Saint Barbara in the Copenhagen painting. In 1634 the work was owned by some unidentified abbot who added his coat of arms with his initiatials "A. A. / Z. G." in right upper corner of the painting. On the other hand, the face of Madonna from a painting in the National Museum in Warsaw (inventory number M.Ob.2542 MNW) is very similar to that of Salome in Munich. This painting is attributed to follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder and dated to the first quarter of the 16th century. The effigy of Salome from the same period by Lucas Cranach the Elder, acquired in 1906 by the Bavarian National Museum in Munich from the Catholic Rectory in Bayreuth, also depict Barbara Jagiellon. A modified copy of this painting by Cranach's workshop or a 17th century copist, possibly Johann Glöckler, with the model shown wearing a dress made of exquisite brocade fabric was in the Heinz Kisters collection in Kreuzlingen in the 1960s (oil on panel, 34.8 × 24.5 cm). It is one of the many known variants of the composition. Possibly around that time or later, when her sister-in-law Bona Sforza ordered her portraits in about 1530, the Duchess also commissioned a series of her portraits as another biblical femme fatale, Judith. The portrait by workshop or follower of Cranach from private collection, sold in 2014, is very similar to the painting in Munich, while the pose essentially corresponds to the portrait of her niece Hedwig Jagiellon from the Suermondt collection, dated 1531. George of Saxony and Barbara Jagiellon were married for 38 years. After her death on 15 February 1534, he grew a beard as a sign of his grief, earning him the nickname the Bearded. He died in Dresden in 1539 and was buried next to his wife in a burial chapel in Meissen Cathedral.

Portrait of Queen Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515), Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony and Catherine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1488-1563), Duchess of Saxe-Lauenburg as the Virgin and Child with Saints Barbara and Catherine by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, National Gallery of Denmark.

Portrait of Queen Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515), Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony and Catherine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1488-1563), Duchess of Saxe-Lauenburg as the Virgin and Child with Saints Barbara and Catherine by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.

Portrait of Queen Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515) and her court ladies as the Virgin and Saints by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, Bode Museum in Berlin, lost.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Salome by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512, Bavarian National Museum in Munich.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Salome by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, after 1512 (17th century?), Private collection.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Judith with the head of Holofernes by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1531, Private collection.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, Private collection.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, Private collection.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as the Virgin of Sorrows by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512-1514, National Gallery in Prague.

Portrait of Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Madonna and Child by follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, first quarter of the 16th century, National Museum in Warsaw.

Portraits of Elizabeth Jagiellon by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop

"Towns and villages are scarce in Lithuania; the main wealth among them are particularly animal skins, to which our age gave the names of Zibellini and armelli (ermine). Unknown use of money, skins take its place. The lower classes use copper and silver; more precious than gold. Noble ladies have lovers in public, with the permission of their husbands, whom they call assistants of marriage. It is a shame for men to add a mistress to their legitimate wife. Marriages are easily dissolved by mutual consent, and they marry again. There is a lot of wax and honey here which wild bees make in the woods. The wine use is very rare, and the bread is very black. Cattle provide food to those who use much milk" (Rara inter Lithuanos oppida, neque frequentes villae: opes apud eos, praecipuae animalis pelles, quibus nostra aetas Zibellinis, armellinosque nomina indidit. Usus pecuniae ignotus, locum eius pelles obtinent. Viliores cupri atque argenti vices implent; pro auro signato, pretiosiores. Matronae nobiles, publice concubinos habent, permittentibus viris, quos matrimonii adiutores vocant. Viris turpe est, ad legitimam coniugem pellicem adiicere. Solvuntur tamen facile matrimonia mutuo consensu, et iterum nubunt. Multum hic cerae et mellis est quod sylvestres in sylvis apes conficiunt. Vini rarissimus usus est, panis nigerrimus. Armenta victum praebent multo lacte utentibus.), wrote in the mid-15th century Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, 1405-1464) in his texts published in Basel in 1551 by Henricus Petrus, who also published the second edition of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium by Nicolaus Copernicus (Aeneae Sylvii Piccolominei Senensis, qui post adeptum ..., p. 417). Some conservative 19th century authors, clearly shocked and terrified by this description, have suggested that the Pope was lying or spreading false rumors.

Elizabeth Jagiellon, the thirteenth and the last child of Casimir IV, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania and his wife Elizabeth of Austria (1436-1505), was most probably born on November 13, 1482 in Vilnius, when her mother was 47 years old. In 1479 Elizabeth of Austria with her husband and younger children, left Kraków for Vilnius for five years. The Princess was baptized with her mother's name. Just few months later on March 4, 1484 in Grodno died Prince Casimir, the heir apparent and future saint, and was buried in the Vilnius Cathedral. Casimir IV died in 1492 in the Old Grodno Castle in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After her father's death Elizabeth strengthen her relationship with her mother. In 1495, together with her mother and sister Barbara, she returned to Lithuania to visit her brother Alexander Jagiellon, Grand Duke of Lithuania. When she was 13 years old, in 1496, John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg intended to marry her to his son Joachim, but the marriage did not materialize and on April 10, 1502 Joachim married Elizabeth of Denmark, daughter of King John of Denmark. In 1504, Alexander, who became the king of Poland in 1501, granted her a jointure (lifetime provision), secured on Łęczyca, Radom, Przedecz and the village of Zielonki. Between 1505-1509, the Voivode of Moldavia, Bogdan III the One-Eyed, sought to win Elizabeth's hand, but the girl was categorically against it. In the following years, marriage proposals from the Italian, German and Danish princes were considered, and it was even planned to marry Elizabeth to the widowed Emperor Maximilian I, who was over 50 when in 1510 died his third wife Bianca Maria Sforza. In 1509 Princess Elizabeth purchased a house at the Wawel Hill from the cathedral vicars, situated between the houses of Szydłowiecki, Gabryielowa, Ligęza and Filipowski and her brother, king Sigismund I, commissioned in Nuremberg a silver altar for the Wawel Cathedral after victory over Bogdan III the One-Eyed, created in 1512 by Albrecht Glim. Elizabeth also raised the children of the king. Without waiting for a clear response from Emperor Maximilian, Sigismund and his brother Vladislaus II decided to marry their sister to Duke Frederick II of Legnica. First, however, Sigismund wanted to communicate with his sister for her opinion. "We have no doubts, that she would easily agree to everything that Your Highness and We will consider right and grateful", he wrote to Vladislaus. The union was supposed to strengthen King Sigismund's ties with the Duchy of Legnica. The marriage contract was signed in Kraków on September 12, 1515 by John V Thurzo, Bishop of Wrocław, who was replacing the groom. Elizabeth received a dowry of 20,000 zlotys, of which 6,000 were to be paid upon marriage, 7,000 on St. Elizabeth's day in a year, and the last 7,000 on St. Elizabeth's day in 1517. In addition, the princess was given a trousseau in gold, silver, pearls and precious stones, estimated at 20,000 zlotys, apart from the robes of gold and silk and ermine and sable furs. The husband was to transfer a jointure of 40,000 zlotys, secured on all income from Legnica and to pay her annually 2,400 zlotys. On November 8, 1515, Elizabeth set off for Legnica from Sandomierz, accompanied by Stanisław Chodecki, Grand Marshal of the Crown, priests Latalski and Lubrański, voivode of Poznań and bishop Thurzo. The wedding of 32-year-old Elizabeth with 35-year-old Frederick took place on November 21 or 26 in Legnica and the couple lived in the Piast castle there. On February 2, 1517, she gave birth to a daughter, Hedwig, who died two weeks later, followed her mother on February 17. The duchess was buried in the Carthusian church in Legnica and in 1548, her body was transferred to another temple in Legnica - the Church of St. John. A painting of Lucretia, the epitome of female virtue and beauty, by Lucas Cranach the Elder or his workshop was acquired by Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Kassel from the art dealer Gutekunst in Stuttgart in 1885. According to inscription on reverse of the panel it was earlier in private collection in Augsburg, a city frequently visited by Emperor Maximilian I. The tower on a hilltop visible on the left in the background is astonishingly similar to the dominant of the 16th century Vilnius, the medieval Gediminas Tower of the Upper Castle. Lucretia's pose, costume and even facial features are very similar to the portrait of Elizabeth's elder sister Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony as Lucretia from Wilhelm Löwenfeld's collection in Munich. A study drawing for this painting by an artist from Cranach's studio, possibly a student sent to Poland-Lithuania to prepare initial drawings, is in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar (CC 100). The same woman was also depicted as reclining water nymph Egeria, today in the Grunewald hunting lodge in Berlin. The painter most likely used the same template drawing to create both effigies (in Kassel and in Berlin). Egeria, the nymph of the sacred source, probably a native Italic water goddess, had the power to assist in conception. "Her fountain was said to have sprung from the trunk of an oak tree and whoever drank it water was blessed with fertility, prophetic visions, and wisdom" (after Theresa Bane's "Encyclopedia of Fairies in World Folklore and Mythology", p. 119). Medieval tower on a steep slope in the background is also similar on both paintings. This painting was presumably in the Berlin City Palace since the 16th century and in 1699 it was recorded in the Potsdam City Palace. It cannot be excluded that it was sent to Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg or his brother Albert of Brandenburg, future cardinal, or it was taken from Poland during the Deluge (1655-1660). Initial drawing for this painting is in the Graphic Collection of the Erlangen University Library (H62/B1338). Another similar Lucretia was sold in Brussels in 1922. Brussels was a capital of the Habsburg Netherlands, a dominium of Emperor Maximilian. It is highly possible that his daughter Archduchess Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515, who resided in nearby Mechelen, received a portrait of possible stepmother. This portrait is also very similar to another portrait of Elizabeth's sister Barbara as Lucretia, which was auctioned in London in 1920. The Lucretia from Brussels was copied in another painting, today in Veste Coburg, which according to later inscription is known as Dido the Queen of Carthage. It was initially in the Art Cabinet (Kunstkammer) of the Friedenstein Palace in Gotha, like the portrait of Elizabeth's niece Hedwig Jagiellon by Cranach from 1534. The costume of Dido is very similar to the dress of Salome visible in a painting of the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (Kroměříž Castle), dated '1515' and created by Cranach for Stanislaus Thurzo, Bishop of Olomouc, brother of Bishop John V Thurzo. This painting bears the inscription in Latin DIDO REGINA and date M.D.XLVII (1547). Friedenstein Palace was built for Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Gotha, and one of the most important events in the history of his family was the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, lost by his great-grandfather John Frederick I, who was stripped of his title as Elector of Saxony and imperial forces blew up the fortifications of Grimmenstein Castle, the predecessor of the Friedenstein Palace. It is possible that a portrait of Elizabeth as Lucretia, whose identity was already lost by 1547, become for John Frederick's family a symbol of their glorious past and tragic fall, exactly like in the Story of Dido and Aeneas. The same facial features were also used in a series of paintings of Nursing Madonna (Madonna lactans), a symbol of maternity and Virgin's capacity for protection. This popular image of Mary with the infant Jesus is similar to the ancient statues of Isis lactans that is the Egyptian goddess Isis, worshiped as the ideal, fertile mother, shown suckling her son Horus. The best version is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. This painting was donated to the museum in 1912 by Count János Pálffy from his collection in the Pezinok Castle in Slovakia. The painting was earlier, most probably, in Principe Fondi's collection which was auctioned in Rome in 1895. The work is exquisitely painted and the landscape in the background resemble the view of Vilnius and Neris river in about 1576, however the face, was not very skilfully added to the painting, most likely as the last part, and the whole effigy looks unnatural. The same mistake was replicated in copies and the face of the Virgin in the copy in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt has almost grotesque appearance. The latter painting was acquired before 1820, probably from the collection of the Landgraves of Hesse-Darmstadt and the hilltop tower behind the Virgin is almost identical with that in the painting of Lucretia in Kassel. Other versions are in the Capuchin monastery in Vienna, most probably from the Habsburg collection, one was sold in Lucerne in 2006 (Galerie Fischer) and another in 2011 in Prague (Arcimboldo). The sitter's face in all mentioned effigies with distinguish Habsburg/Masovian lip, resemble greatly Elizabeth's sister Barbara Jagiellon, her mother Elizabeth of Austria and her brother Sigismund I. There is also a painting in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, created by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, representing the Virgin Mary flanked by two female saints, very similar to the compositions in the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen and in the Bode Museum in Berlin, lost during World War II. The painting was acquired before 1932 on the Berlin art market. The effigy of Mary is a copy of a painting in Strońsko near Sieradz in central Poland, the portrait of Barbara Zapolya. The woman on the left, receiving an apple from the Child, is identical with effigies of Barbara Jagiellon, Duchess of Saxony and the one on the right resemble Elizabeth Jagiellon. The castle in the background match perfectly the layout of the Royal Sandomierz Castle in about 1515 as seen from the west. The Gothic castle in Sandomierz was built by king Casimir the Great after 1349 and it was rebuilt and extended in about 1480. On July 15, 1478 Queen Elizabeth of Austria gave birth to Barbara Jagiellon there and the royal family lived in the castle from about 1513. In 1513 Sigismund I ordered to demolish some ruined, medieval structures and to extend and reconstruct the building in the renaissance style. Two-storey arcaded cloisters around a closed courtyard (west, south and east wings) were constructed between 1520-1527. The castle was destroyed during the Deluge in 1656 and the west wing was rebuilt between 1680-1688 for King John III Sobieski.

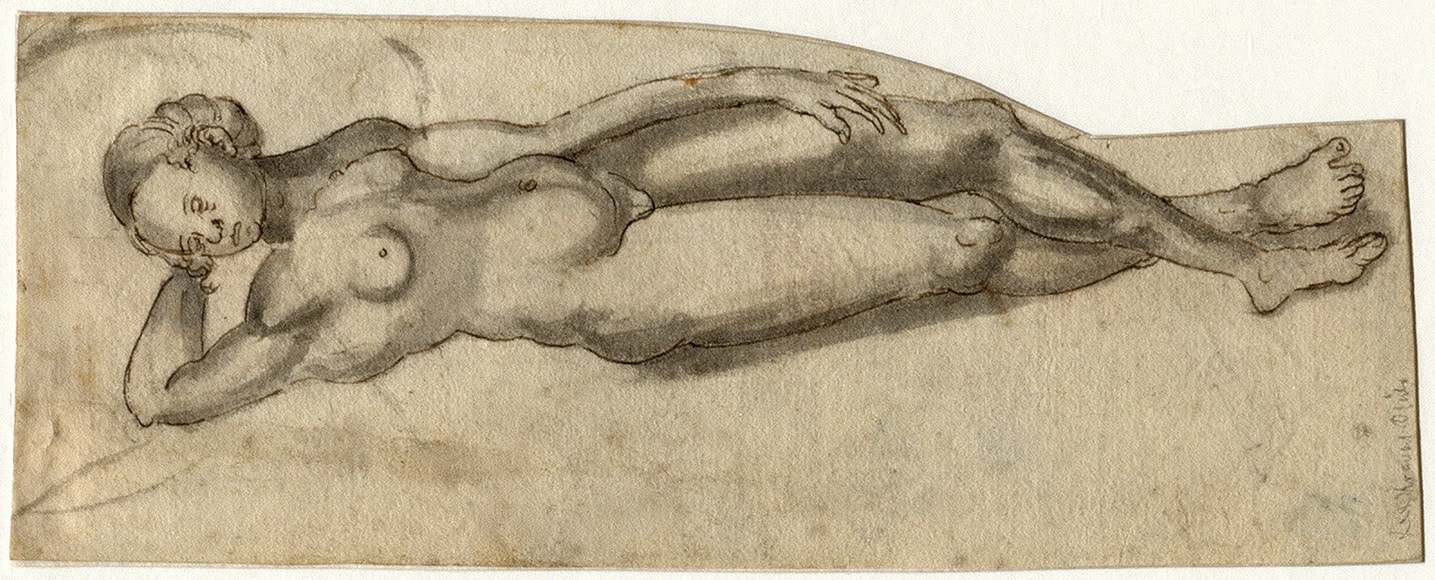

Study drawing for portrait of Princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) as reclining water nymph Egeria by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1510-1515, Graphic Collection of the Erlangen University Library.

Portrait of Princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) as reclining water nymph Egeria by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1510-1515, Grunewald hunting lodge.

Study drawing for portrait of Princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) as Lucretia by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1510-1515, Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

Portrait of Princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder or workshop, ca. 1510-1515, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Kassel.

Portrait of Princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder or workshop, ca. 1510-1515, Private collection.

Portrait of Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517), Duchess of Legnica as Lucretia (Dido Regina) by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1515, Veste Coburg.

Portrait of Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517), Duchess of Legnica as Madonna lactans by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1515, Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest.

Portrait of Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517), Duchess of Legnica as Madonna lactans by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1515, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt.

Portrait of Queen Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515), Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony and Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517), Duchess of Legnica as the Virgin flanked by two female saints by workshop or follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1515, Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

Portraits of George I of Brzeg and Anna of Pomerania by Hans Suess von Kulmbach

On June 9, 1516 in Szczecin, Duke George I of Brzeg (1481-1521) married Anna of Pomerania (1492-1550), the eldest daughter of Duke Bogislaw X of Pomerania (1454-1523) and his second wife Anna Jagiellon (1476-1503), daughter of King Casimir IV of Poland.

According to Brzeg city book (fol. 24 v.) their engagement took place as early as 1515. In June 1515, George imposed a two-year tax on the inhabitants of his Duchy in order to collect dowry sums of 10,000 guilder (after "Piastowie: leksykon biograficzny", p. 507), the sum the princess also received from her father. In the years 1512-1514 there were negotiations regarding Anna's marriage with the Danish king Christian II. This marriage was prevented by the Hohenzollerns, leading to his marriage to Isabella of Austria, sister of Emperor Charles V. George, the youngest son of Duke Frederick I, Duke of Chojnów-Oława-Legnica-Brzeg-Lubin, by his wife Ludmila, daughter of George of Poděbrady, King of Bohemia, was the true prince of the Renaissance, a great patron of culture and art. Often staying at the court in Vienna and Prague, he got used to splendor, so that in 1511, during the stay of the Bohemian-Hungarian royal family in Wrocław, all courtiers were eclipsed by the splendor of his retinue. In February 1512 he was in Kraków at the wedding of King Sigismund I with Barbara Zapolya, arriving with 70 horses, then in 1515 at the wedding of his brother with the Polish-Lithuanian princess Elizabeth Jagiellon (1482-1517) in Legnica, and in 1518 again in Kraków at the wedding of Sigismund with Bona Sforza. He imitated the customs of the Jagiellonian courts in Kraków and Buda, had numerous courtiers, held feasts and games at his castle in Brzeg (after "Brzeg" by Mieczysław Zlat, p. 21). He died in 1521 at the age of 39. George and Anna had no children and according to her husband's last will, she received the Duchy of Lubin as a dower with the lifelong rights to independent rule. Anna's rule in Lubin lasted twenty-nine years, and after her death it fell to the Duchy of Legnica. The major painter at that time at the royal court in Kraków was Hans Suess von Kulmbach. His work is documented between 1509-1511 and 1514-1515, working for the king Sigismund I (his portrait in Gołuchów, Pławno triptych, a wing from a retable with effigy of a king, identified as portrait of Jogaila/Ladislaus Jagiello, in Sandomierz, among others), his banker Jan Boner (altar of Saint Catherine) and his nephew Casimir, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach from 1515 (his portrait dated '1511' in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich). Hans, born in Kulmbach, was a student of the Venetian painter Jacopo de' Barbari (van Venedig geporn, according to Dürer) and then went to Nuremberg, where he became close friends with Albrecht Dürer as his assistant. The portrait of a man by Kulmbach in private collection (auctioned at Sotheby's, London in 1959) bear inscription · I · A · 33 (abbreviation for Ihres Alters 33 in German, his age 33, in upper left corner), monogram of the painter HK (joined) and above the year 1514 (in upper right corner). The man was the same age as Duke George I of Brzeg, born according to sources between 1481 and 1483 (after "Piastowie: leksykon biograficzny", p. 506), when Kulmbach moved to Kraków. This portrait has its counterpart in another painting of the same format and dimensions (41 x 31 cm / 40 x 30 cm), portrait of a young woman in Dublin (National Gallery of Ireland, inventory number NGI.371, purchased at Christie's, London, 2 July 1892, lot 15). Both portraits were painted on limewood panels, they have a similar, matching composition and similar inscription. According to the inscription on the portrait of a woman, she was 24 in 1515 (· I · A · 24 / 1515 / HK), exaclty as Anna of Pomerania, born at the end of 1491 or in the first half of 1492 (after "Rodowód książąt pomorskich" by Edward Rymar, p. 428), when she was engaged to George I of Brzeg. The woman bear a strong resemblance to effigies of Anna of Pomerania by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop, identified by me. Her costume is very similar to that visible in the painting depicting Self-burial of St. John the Evangelist (St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków), created by Kulmbach in 1516, possibly showing the interior of the Wawel Cathedral with original gothic, silver sarcophagus of Saint Stanislaus. The female figures in the latter painting could be Queen Barbara Zapolya (d. 1515) and her ladies or wife of Jan Boner, Szczęsna Morsztynówna and other Kraków ladies. Despite different dates, the two portraits are also considered as a possible pair in the exhibition catalog "Meister um Albrecht Dürer" at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg in 1961, according to which "the figures probably represent people from Kraków, because Kulmbach worked there in 1514/15 on the altar of St. Catherine of the St. Mary's Church" (Dargestellt dürften Krakauer Persönlichkeiten sein, da Kulmbach dort 1514/15 am Katharinenaltar für die Marienkirche arbeitete, compare "Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums", items 166-167, p. 107). The portraits are also compared to two similar paintings depicting a woman and her husband, which were before 1913 in the collection of Marczell Nemes (1866-1930) in Budapest, sold in Paris, and earlier in the Weber collection in Hamburg (after "Collection Marczell de Nemes", Galerie Manzi-Joyant, items 26-27). Both paintings were probably destroyed during the First or Second World War. The portrait of a woman (panel, 58.5 x 44), wearing expensive jewelry indicating her wealth, was signed with the artist's monogram and dated: J. A. Z. 4. / 1.5.1.3. HK, which means that the woman was 24 years old in 1513. The portrait of a man (panel, 58 x 43.5) was also signed with the artist's monogram and dated: J. A. Z. 7. / 1.5.1.3. HK, indicating that the model was 27 years old in 1513. The age of a man in 1513 perfectly matches Seweryn Boner (1486-1549), a wealthy banker to King Sigismund I, whose family moved from Nuremberg to Kraków in 1512 and who throughout his life maintained active contact with this German city. Boner's year of birth - 1486, is confirmed on his bronze funerary sculpture in St. Mary's Church in Kraków, created between 1532 and 1538 by Hans Vischer in Nuremberg. According to a Latin inscription, he died in 1549 at the age of 63 (SANDECEN(SIS) ANNV(M) ÆTATIS SVÆ SEXAGESIMV(M) · TERCIV(M) AGE(N)S DIE XII MAY A[NNO] 1549). Seweryn married the daughter of Severin Bethman of Wissembourg (d. 1515) and his wife Dorothea Kletner - Sophia Bethman (d. 1532), also Zofia Bethmanówna (MAGNIFICÆ DOMINÆ ZOPHIÆ BETHMANOWNIE. QVÆ. DIE V MAII AN[NO] MDXXXII OBIIT), according to the inscription on her funerary sculpture, or Sophie Bethmann in German sources, born around 1490, her age therefore also corresponds to that of a woman in the Kulmbach's portrait (around 1489). Zofia was a heiress of Balice and her wealth helped build Boner's successful career. The effigies of a woman and a man also recall Seweryn and Zofia from their funerary sculptures. Although Kulmbach apparently returned to Nuremberg in 1513, that year he painted a votive panel for Provost Lorenz Tucher to Saint Sebaldus in Nuremberg, considered his most important work (signed right in middle panel: HK 1513), the direct meeting with Seweryn Boner around that year is not excluded (whether in Nuremberg or Kraków). The man's costume in the 1513 portrait is typical for Kraków fashion of that era and similar ones can be seen in Hans von Kulmbach's 1511 Adoration of the Magi, the central panel of a triptych founded by Stanisław Jarocki, castellan of Zawichost (d. 1515) for Skałka Monastery in Kraków (Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, inv. 596A). It also greatly resembles the outfit of King Sigismund from his portrait attributed to Kulmbach at Gołuchów Castle (oil on panel, 24 x 18 cm, Mo 2185) or from his portrait, most likely made by Kulmbach, which was at the beginning of the 20th century in the antique shop of Franciszek Studziński in Paris. Regarding the effigy of the king in Gołuchów, it should also be noted that although it is undoubtedly a version of the same prototype, most likely made by Kulmbach, which was also copied by Cristofano dell'Altissimo in a painting in the Uffizi Gallery (inv. 1890, n. 412), the style of the painting more closely resembles to the works of Flemish painters of the 17th century. The most striking element of the two mentioned portraits of Sigismund I is the way in which the nose was depicted and perfectly illustrates how the practice of copying effigies changed facial features. According to Mieczysław Morka ("Sztuka dworu Zygmunta I Starego ...", p. 450, 452), it is probably King Sigismund I who shakes the hand of Saint Joseph, spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in the Adoration of the Magi from Skałka, however, the golden crinale cap and green cloak of a man are very similar to the portrait of a man from 1513. The woman's costume, with its characteristic bulbous coif, called Wulsthaube, also finds equivalents in Kraków fashion in the Miracle at the tomb of the Patriarch from the polyptych of John the Merciful, painted by Jan Goraj around 1504 (National Museum in Kraków, MNK ND-13), founded by Mikołaj of Brzezie Lanckoroński for the Church of St. Catherine in Kraków. A similar dress can be seen in the miniature portrait of Agnieszka Ciołkowa née Zasańska (d. 1518) as Saint Agnes in the Kraków Pontifical by the Master of the Bright Mountain Missal from 1506 to 1518 (Czartoryski Library, 1212 V Rkps, p. 37). Aa a wealthy merchant and banker, sometimes compared to Jakob Fugger the Rich (1459-1525), Seweryn Boner was a great patron of the arts. His family, especially his uncle Jan or Johann (Hans) Boner (1462-1523), were also known for their splendid patronage. In addition to Kulmbach paintings, Hans bought luxury items in Venice. The beautiful Renaissance tombstone of Seweryn's father-in-law, Severin Bethman, in the presbytery of St. Mary's Church in Kraków, carved from red marble, is most likely the work of Giovanni Cini. The only thing preventing us from fully recognizing the 1513 portraits as effigies of Zofia and her husband is the date of the paintings. According to sources, she married Seweryn on October 23, 1515, so two years later. A few days after the wedding, her father died (October 28). Nevertheless, this does not completely rule out identification as Zofia Bethmanówna and Seweryn Boner. The exact source confirming the date of their marriage is not specified, so it could be incorrect. The date of their engagement is also not known. Although, according to traditional iconography, the portraits represent a married couple (pendant portraits, woman's hair covered), as in the case of the portraits made in 1514 and 1515, described above, the interpretation that they were made not as confirmation but as anticipation of a successful marriage is also possible.

Portrait of a woman aged 24, probably Zofia Bethmanówna (d. 1532) by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1513, Private collection, lost. Virtual reconstruction, © Marcin Latka

Portrait of a man aged 27, probably Seweryn Boner (1486-1549) by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1513, Private collection, lost. Virtual reconstruction, © Marcin Latka

Portrait of George I of Brzeg (1481-1521), aged 33 by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1514, Private collection.

Portrait of Anna of Pomerania (1492-1550), aged 24 by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1515, National Gallery of Ireland. If you would like to sponsor a better quality reproduction, please contact me here.

Portrait of Sigismund I (1467-1548) by Hans Suess von Kulmbach (?), after 1514, Private collection, lost. Virtual reconstruction, © Marcin Latka

Portrait of Sigismund I (1467-1548) by Flemish painter after Hans Suess von Kulmbach (?), first quarter of the 17th century, Gołuchów Castle.

Disguised portraits of Szczęsna Morsztynówna by Hans Suess von Kulmbach

Renaissance painters frequently placed religious scenes in surroundings that they knew from everyday life. This kind of Renaissance mimesis reproduced reality and, as it included real people in the form of saints and historical figures, interiors and landscapes, it gave rise to other genres, such as portraiture, still life or the landscape.

The wealthy patrons who commissioned such religious scenes often wanted to be included, either as donors or protagonists. Sometimes they also wanted to show off their wealth and power, like Nicolas Rolin (1376-1462), chancellor of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and one of the richest and most powerful men of his time. In the so-called Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, painted by Jan van Eyck around 1435 (Louvre, INV 1271; MR 705), the chancellor kneels before the Virgin herself in a splendid room or chapel offering a magnificent view. German painter Hans Suess von Kulmbach during the creation of panels of the Altar of Saint Catherine and the Altar of Saint John for the Church of Saint Mary in Kraków, created between 1514 and 1519, also inspired by real life. Both cycles are considered to have been created in Kraków on the orders of the merchant and banker Johann (Hans) Boner (1462-1523), also Hannus Bonner (Bonar, Ponner), a native of Landau in the Palatinate, who settled in Kraków in 1483. Unfortunately, several paintings from these cycles, as well as other paintings by Kulmbach, were lost after the Nazi German invasion of Poland in 1939. Around 1493, Johann married Szczęsna Morsztynówna (died before 1523), Felicia Morrensteyn or Morstein in German sources, the youngest daughter of Stanislaus Morsztyn the Elder, a patrician from Kraków, who brought him houses worth 2,000 zlotys as a dowry. In 1498 he became a city councilor. In 1514 he was ennobled (Bonarowa coat of arms) and obtained the office of burgrave of Kraków Castle, then the starosty of Rabsztyn and Ojców. In 1515 he became manager of the Wieliczka salt mines and was at that time the main banker of Sigismund I. As a painter of the Boner family, who enjoyed special royal protection, Kulmbach did not need to join the Kraków painters' guild, which probably explains why the city documents did not preserve his name. Johann probably met the painter while serving as intermediary between King Sigismund I and his sister Sophia Jagiellon (1464-1512), Margravine of Brandenburg-Ansbach. He probably carried letters from one court to another, and it is quite possible that he represented the king at Sophia's funeral (after "Hans Suess z Kulmbachu" by Józef Muczkowski, Józef Zdanowski, p. 12). In 1511, the Kraków city council granted him the Chapel of the Holy Spirit in St. Mary's Church, which Pope Leo X approved on July 19, 1513 encouraged by the message provided by the Bishop of Płock, Erazm Ciołek, that the king treated the Boner Chapel with special devotion. In 1513, the chapel received a new patron, Saint John the Baptist, and in 1515 its invocation was supplemented with Saint John the Evangelist. The two cycles were most likely created for this chapel. Most interesting is the panel from the altar of Saint Catherine depicting the Disputation in which Saint Catherine converted pagan philosophers to Christianity (tempera and oil on panel, ca. 118 x 62 cm), as it makes a direct reference to the Boners - their coat of arms in the stained glass quatrefoil which adorns the window. The style of the painting is also very interesting because it refers to Jacopo de' Barbari and Albrecht Dürer, thus joining the Venetian and German tradition, so popular in Poland-Lithuania at that time. The scene obviously takes place in Johann's house in Kraków. Interestingly, apart from paintings by Kulmbach, he also commissioned luxury items from Venice, like exquisit glass pilgrim fask adorned with his coat of arms and mongram (initials H and P), now in the Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon (41.3 cm, inv. D 697). The collection of the Museum of Applied Arts Vienna includes a large footed glass plate which also bears Boner's coat of arms, supplemented by his initials (diameter: 44.9 cm, inv. F 180), and suggests that a large set was probably made for Hans in Venice at the beginning of the 16th century. In 1510/1511, he received the following merchandise from Venice alone: 10,054 pieces of window glass, three crates of Venetian glass (luxury glass), and 4,090 glass containers for everyday use (after "An early 16th century Venetian Pilgrim Flask ..." by Klaas Padberg Evenboer, p. 304, 306, 308). The glass in the windows of his house was certainly also imported from Venice, which is why Boner wanted to boast to the other citizens of Kraków. They were probably designed by Hans Suess - one of his most important drawings, made in Kraków in 1511 (dated upper right) is a tondo with the Martyrdom of Saint Stanislaus, which is most likely a design for a stained glass window (Kunsthalle Bremen, inv. 1937/613). All these elements, combined with a very portrait-like effigy in profile of one of the philosophers on the right, standing directly under the quatrefoil with the coat of arms, indicate that this is the cryptoportrait of Johann. The same man was also depicted on the left of the scene of the self-burial of Saint John the Evangelist, painted in 1516 (St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków), which takes place in the Wawel Cathedral before the original Gothic reliquary-sarcophagus of Saint Stanislaus, as well as one of the Apostles in the Ascension of Christ, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, attributed to Kulmbach and dated around 1513 (oil on panel, 61.5 x 35.9 cm, inv. 21.84, compare "Just what is it that makes identification-portrait hypotheses so appealing? ..." by Masza Sitek, p. 3, 7, 11-12, 17). Other members of the Boner family were also depicted in the paintings commissioned by Johann, including his wife. Already at the beginning of the 20th century, an interpretation was proposed according to which Empress Faustina from the Conversion of the empress was the disguised portrait of Johann's wife. The empress is the secondary figure of the cycle, while Szczęsna was the central female figure in Johann's life and household, just like Saint Catherine in the Dispute scene by Kulmbach. The woman in rich crimson attire, typical for the Polish nobility, wearing a pearl necklace and a headpiece decorated with pearls (symbols of the Virgin Mary and Venus), points towards the quatrefoil with the image of the Madonna and Child. As the mystical bride of Christ, Saint Catherine ranked second only to the Virgin Mary. The painting of the Madonna also played a decisive role in the conversion of the pagan-born princess, as shown in the first panel of the Kulmbach cycle. A lapdog at her feet, a symbol of marital fidelity, similar to that visible in portrait of Catherine of Mecklenburg, painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1514 (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, 1906 H), indicate that she is a wealthy lady of the Renaissance. Her costume reflects her husband's status and the fashion of Kraków at that time. It is comparable to the dresses of the ladies in the Miracle at the tomb of the Patriarch from the polyptych of John the Merciful, painted by Jan Goraj around 1504 (National Museum in Kraków, MNK ND-13) or costume of Agnieszka Ciołkowa née Zasańska (died 1518), depicted as Saint Agnes in the Kraków Pontifical from 1506 to 1518 (Czartoryski Library, 1212 V Rkps, p. 37). The clothing of the wife of Erazm Schilling (d. 1561) from Kraków is so rich that her portrait was considered to represent Sibylle of Cleves (1512-1554), electress of Saxony. It was sold as a pendant to the portrait of Frederick III the Wise (1463-1525), prince-elector of Saxony, who was never married (Lempertz in Cologne, Auction 1017, September 25, 2013, lot 112). All copies of this portrait were probably painted by the Nuremberg painter Franz Wolfgang Rohrich (1787-1834), who also copied the portrait of Sigismund I's sister Sophia (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 07.245.2), yet, one copy bears an inscription in German confirming that the woman was a daughter of Stenzel from Poznań and that she married Erazm in 1521. The coat of arms of the Silesian noble family Schilling joined to that of the woman also confirms that she was the wife of this patrician of Kraków (oil on panel, 64.5 x 46 cm, Galeria Staszica in Poznań, December 15, 2022, lot 3, inscription: ANNO MDXXI IST DEM EDLENE VND VESTEN ERASMO SCHILLINGIN CROCAVVER ...). The Venetian-style portrait of the Kraków goldsmith Grzegorz Przybyła or Przybyło (d. 1547) and his wife Katarzyna (d. 1539) is another confirmation of the great prosperity of the Kraków bourgeoisie at the beginning of the 16th century (National Museum in Warsaw, inv. 128874). The big décolletage of Szczęsna's dress in turn confirms that it was popular in Poland-Lithuania long before Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga (1611-1667), who is said to have introduced it upon her arrival in 1646.

Tondo drawing with Martyrdom of Saint Stanislaus by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1511, Kunsthalle Bremen.

Conversion of Saint Catherine with disguised portrait of Szczęsna Morsztynówna by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1515, St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków.

Disputation of Saint Catherine with pagan philosophers with disguised portraits of Szczęsna Morsztynówna and her husband Johann Boner (1462-1523) by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1515, St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków.

Self-burial of St. John the Evangelist with portrait of Johann Boner (1462-1523) by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, 1516, St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków.

Portrait of wife of Erazm Schilling (d. 1561), patrician of Kraków, by Franz Wolfgang Rohrich (?), before 1834 after original from the 1520s, Private collection.

Portraits of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino by Venetian painters

"As to Florence, 1513 also saw another Medici, Lorenzo de' Medici (the grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent), return to power as a 'leading citizen,' a development felicitous to some, odious to others. He too pursued the Medici drive toward expansion, desiring, and with the help of his uncle the pope, achieving the title of duke of Urbino in 1516. It was to him, in fact, that Machiavelli wound up dedicating The Prince, in the hope, vain in retrospect, that Lorenzo might become the sought-after redeemer of Italy for whom The Prince's final lines cry out so urgently. As duke of Urbino he married a daughter of the count of Auvergne, with whom he had a daughter, Catherine de' Medici, who would later become queen of France" (after Christopher Celenza's "Machiavelli: A Portrait", p. 161).

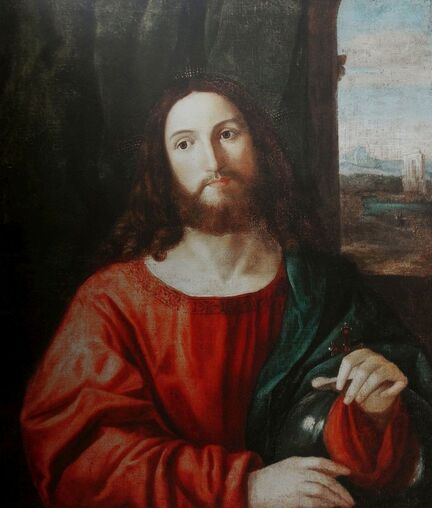

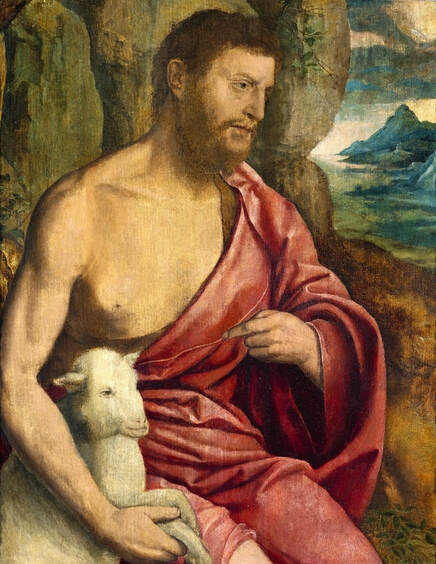

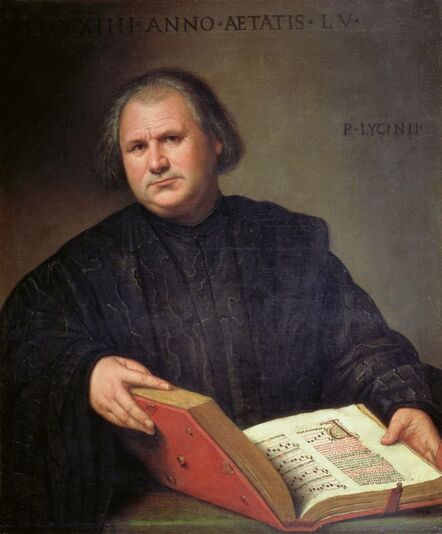

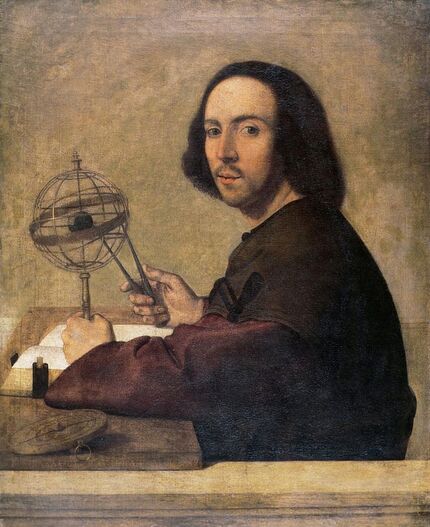

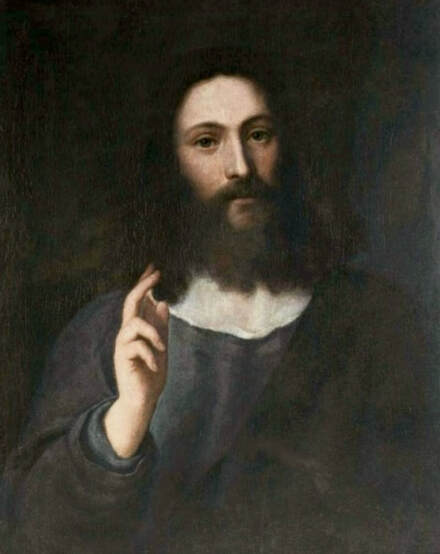

Lorenzo, born in Florence on 12 September 1492, received the name of his eminent paternal grandfather Lorenzo the Magnificent. Just as for his grandfather, Lorenzo's emblem was the laurel tree, because of the play on the words laurus (laurel) and Laurentius (Lorenzo, Lawrence). A bronze medal cast by Antonio Francesco Selvi (1679-1753) in the 1740s, believed to be inspired by the medal created by Francesco da Sangallo (1494-1576), depict the duke in profile with inscription in Latin LAVRENTIVS. MEDICES. VRBINI.DVX.CP. on obverse and a laurel tree with a lion, generally regarded as symbol of strength, on either side with the motto that says: .ITA. ET VIRTVS. (Thus also is virtue), to signify that virtue like laurel is always green. Another medal by Sangallo in the British Museum (inventory number G3,TuscM.9) also shows laurel wreath around field on reverse. The so-called "Portrait of a poet" by Palma Vecchio in the National Gallery in London, purchased in 1860 from Edmond Beaucousin in Paris, is generally dated to about 1516 basing on costume (oil on canvas, transferred from wood, 83.8 x 63.5 cm, NG636). The laurel tree behind the man have the same symbolic meaning as laurel on the duke of Urbino's medals and his face resemble greatly effigies of Lorenzo de' Medici by Raphael and his workshop. The same man was also depicted in a series of paintings by Venetian painters showing Christ as the Redeemer of the World (Salvator Mundi). One attributed to Palma Vecchio is on display in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Strasbourg (oil on panel, 74 x 63 cm, MBA 585), the other in the National Museum in Wrocław (oil on canvas, 78.5 x 67.7, VIII-1648, purchased in 1966 from Zofia Filipiak), possibly from the Polish royal collection, was painted more in the style of Giovanni Cariani or Bernardino Licinio, and another in the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston (oil on canvas, 76.8 x 65 cm, 10-011) is attributed to Girolamo da Santacroce from Bergamo, a pupil of Gentile Bellini, active mainly in Venice. This practice of disguised portraits, dressed as Christian saints or members of the Holy Family, was popular among the Medici family since at least the mid-15th century. The best example is a painting commissioned in Flanders - the Medici Madonna with portraits of Piero di Cosimo de' Medici (1416-1469) and his brother Giovanni (1421-1463) as Saints Cosmas and Damian, painted by Rogier van der Weyden between 1460 and 1464 when the artist was working in Brussels (Städel Museum, 850). As in "The Prince" by Machiavelli, the message is clear, "more than just a prince, Lorenzo can become a 'redeemer' who drives out of Italy the 'barbarian domination [that] stinks to everyone'" (after Ben Jones' "Apocalypse without God: Apocalyptic Thought, Ideal Politics, and the Limits of Utopian Hope", p.64).

Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici (1492-1519), Duke of Urbino by Palma Vecchio, ca. 1516, National Gallery in London.

Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici (1492-1519), Duke of Urbino as the Redeemer of the World (Salvator Mundi) by Palma Vecchio, ca. 1516, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg.

Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici (1492-1519), Duke of Urbino as the Redeemer of the World (Salvator Mundi) by Giovanni Cariani or Bernardino Licinio, ca. 1516, National Museum in Wrocław.

Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici (1492-1519), Duke of Urbino as the Redeemer of the World (Salvator Mundi) by Girolamo da Santacroce, ca. 1516, Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya by Lucas Cranach the Elder

In 1535 a lavish wedding ceremony was held at the Wawel Castle in Kraków. Hedwig, the only daughter of Sigismund I the Old and his first wife Barbara Zapolya was married to Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg.

The bride received a big dowry, including a casket, now in The State Hermitage Museum, commissioned by Sigismund I in 1533 and adorned with jewels from the Jagiellon collection, made of 6.6 kg of silver and 700 grams of gold, adorned with 800 pearls, 370 rubies, 300 diamonds and other gems, including one jewel in the shape of letter S. The same monogram is visible on the sleeves of Hedwig's dress in her portrait by Hans Krell from about 1537. A ring with letter S is on the Sigismund I's tomb monument in the Wawel Cathedral and he also minted coins with it. Hedwig undoubtedly took also with her to Berlin a portrait of her mother. The portrait of a woman with necklace and belt with B&S monogram, dated by the experts to about 1512, which was in the Imperial collection in Berlin before World War II, now in private collection (oil on panel, 42 x 30 cm), is sometimes identified as depicting Barbara Jagiellon, Duchess of Saxony and Barbara Zapolya's sister-in-law. A pendant with the monogram of the married couple SH (Sophia et Henricus) is visible on the tombstone of Sophia Jagiellon (1522-1575), Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg, daughter of Sigismund and his second wife Bona Sforza, in the St. Mary's Church in Wolfenbüttel. Such jewelry with monograms, called "letters" (litera/y), were popular and are mentioned in many inventories. Among more than 250 rings of Queen Bona, there was a ring with black enamel, a diamond, rubies and an emerald, on which there were the letters BR (BONA REGINA) and three others with the letter B. Sigismond's daughters, Sophia, Anna and Catherine, owned the jewels with the letters S, A and C from the first letter of their names in Latin of which only Catherine's jewel has survived (Cathedral Museum in Uppsala). They were made in 1546 by Nicolas Nonarth in Nuremberg and depicted in their portraits by the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Younger. Florian, court goldsmith between 1502-1540, elder of the guild in 1511 was paid in the years 1510-1511 for various works for the king and his illegitimate son John (1499-1538), later bishop of Vilnius and Poznań. He made silver belts for the king, a base for a clock, harnesses for horses, cups for king's mistress Katarzyna Telniczanka and silver utensils for the royal bathroom (after "Mecenat Zygmunta Starego ..." by Adam Bochnak, p. 137). The gold sheet with Saint Barbara made as the background of the painting of Our Lady of Częstochowa is considered to be a gift from Queen Barbara given during a pilgrimage to the monastery on October 27, 1512. The necklace and belt in form of chains with initials is clearly an allusion to great affection, thus the letters must be initals of the woman and her husband. If the painting would be an effigy of Barbara Jagiellon, the initials would be B and G or G and B for Barbara and her husband George (Georgius, Georg), Duke of Saxony. The monogram must be then of Barbara Zápolya and Sigismund I, Hedwig's parents, therefore the portrait is the effigy of her mother.

Portrait of Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515), Queen of Poland with necklace and belt with B&S (Barbara et Sigismundus) monogram by Lucas Cranach the Elder or workshop, ca. 1512-1515, Private collection.

Portraits of King Sigismund I and Queen Barbara Zapolya by workshop of Michel Sittow

From July 15-26, 1515 The First Congress of Vienna was held, attended by the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, and the Jagiellonian brothers, Vladislaus II, King of Hungary and King of Bohemia, and Sigismund I, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. It became a turning point in the history of Central Europe. In addition to the political arrangements, Maximilian and Vladislaus agreed on a contract of inheritance and arranged a double marriage between their two ruling houses. After the death of Vladislaus, and later his son and heir, the Habsburg-Jagiellon mutual succession treaty ultimately increased the power of the Habsburgs and diminished that of the Jagiellons.