|

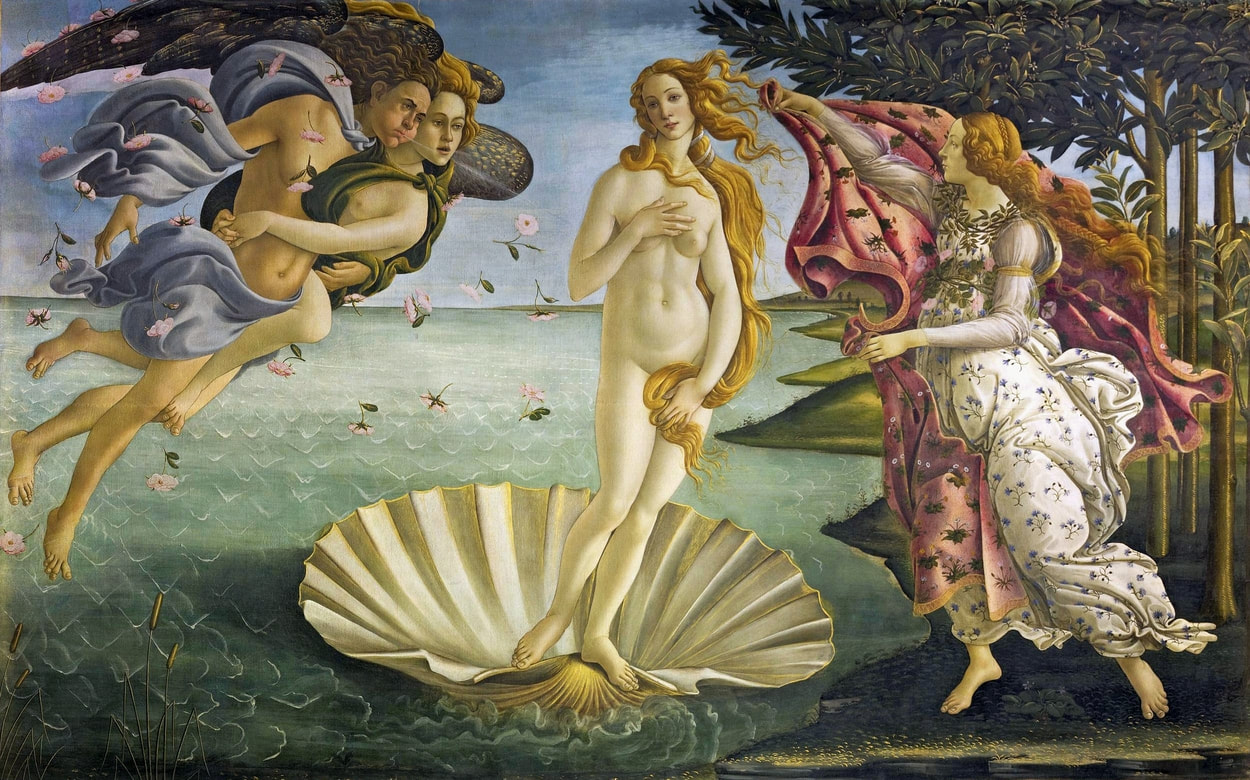

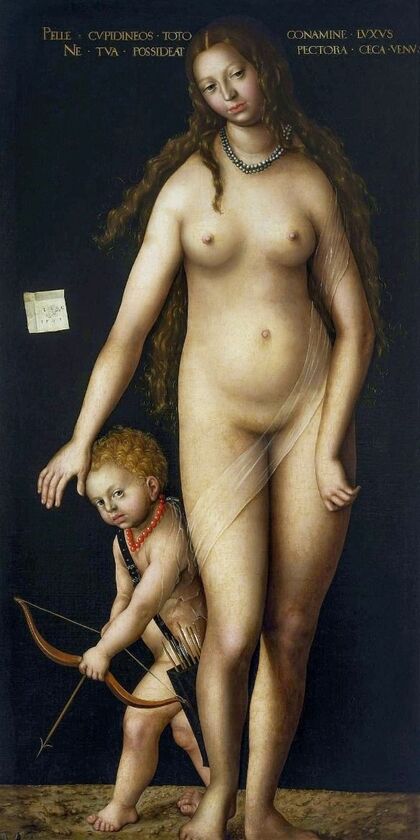

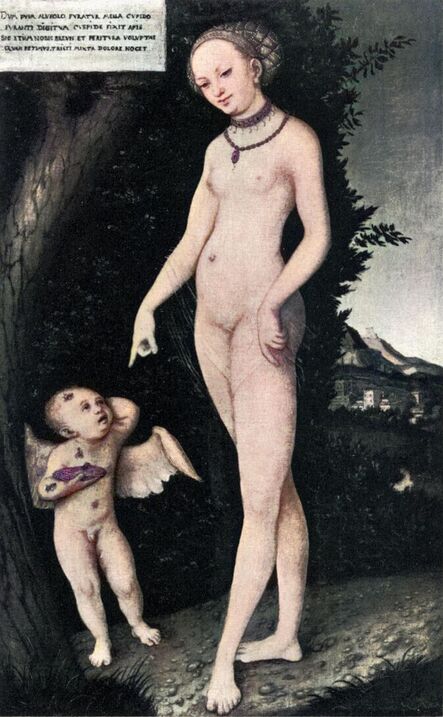

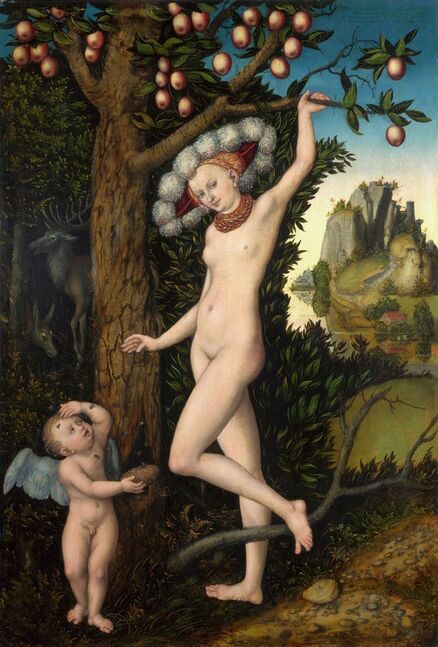

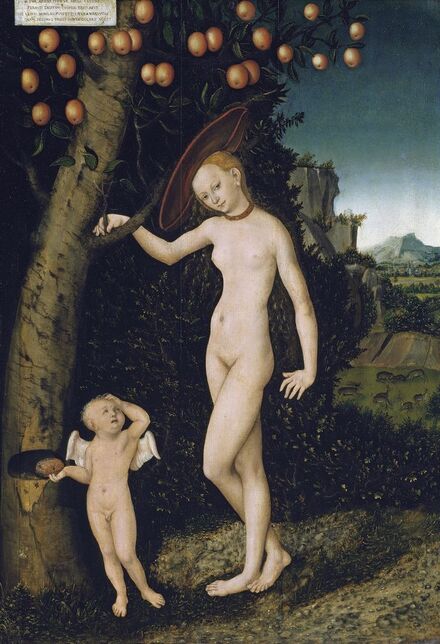

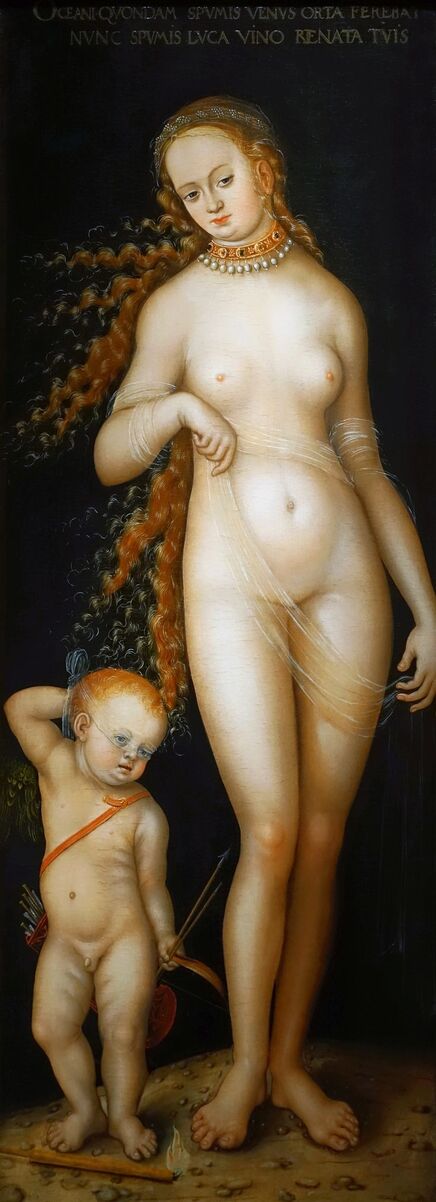

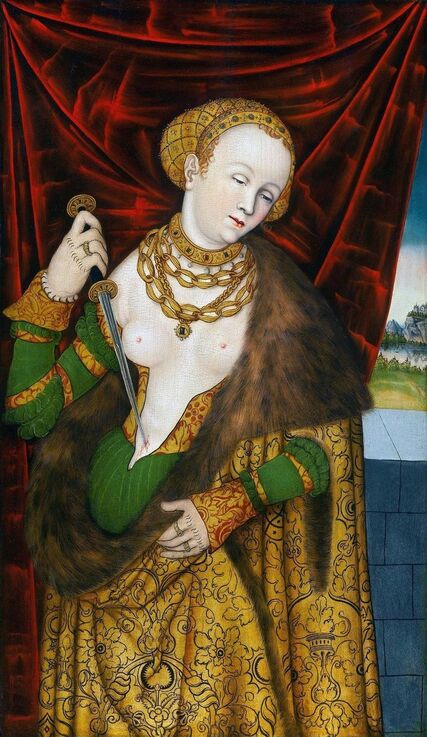

Renaissance Poland-Lithuania - The Realm of Venus, goddess of love, destroyed by Mars, god of war. Discover its "Forgotten portraits", its sovereigns and its unique culture ...

Forgotten portraits - Introduction - part A Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part I (1470-1505) Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part II (1506-1529) Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part III (1530-1540) Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part IV (1541-1551) Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part V (1552-1572) Forgotten portraits of the Jagiellons - part VI (1573-1596) Forgotten portraits - Introduction - part B Forgotten portraits of the Polish Vasas - part I (1587-1623) Forgotten portraits of the Polish Vasas - part II (1624-1636) Forgotten portraits of the Polish Vasas - part III (1637-1648) Forgotten portraits of the Polish Vasas - part IV (1649-1668) Forgotten portraits of the "compatriot kings" (1669-1696)

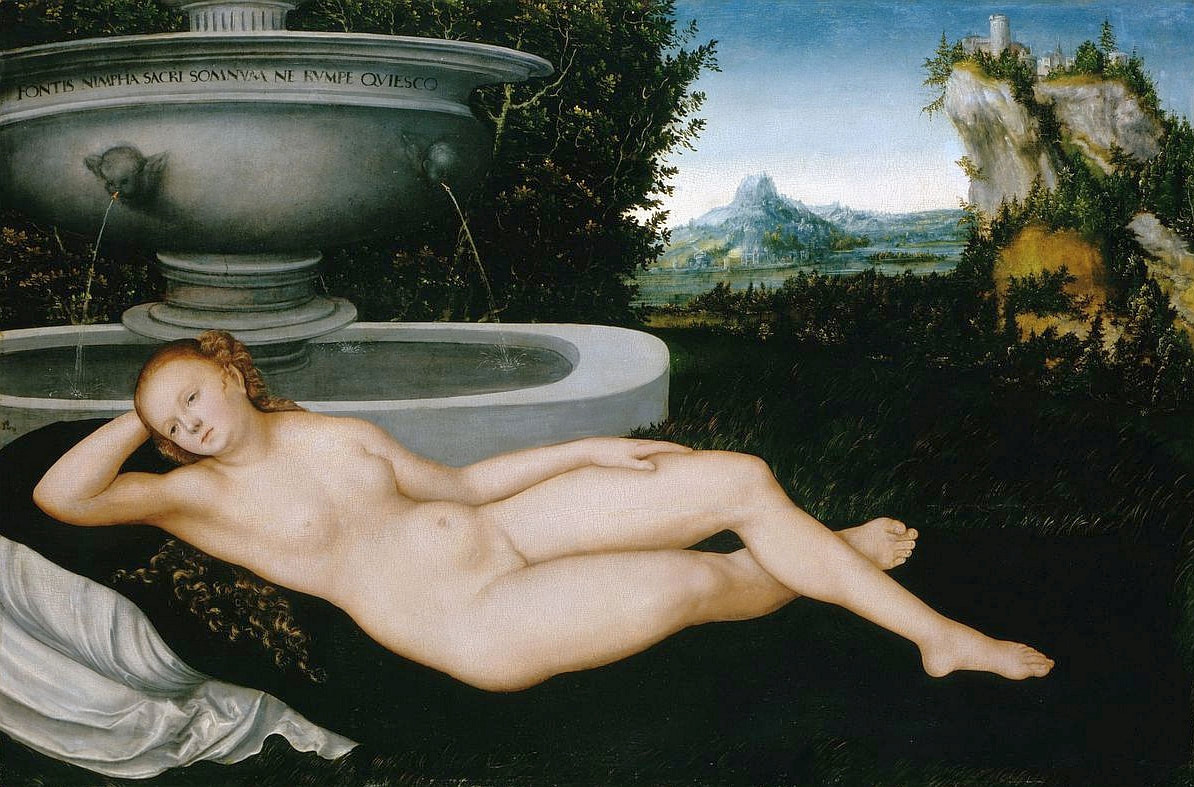

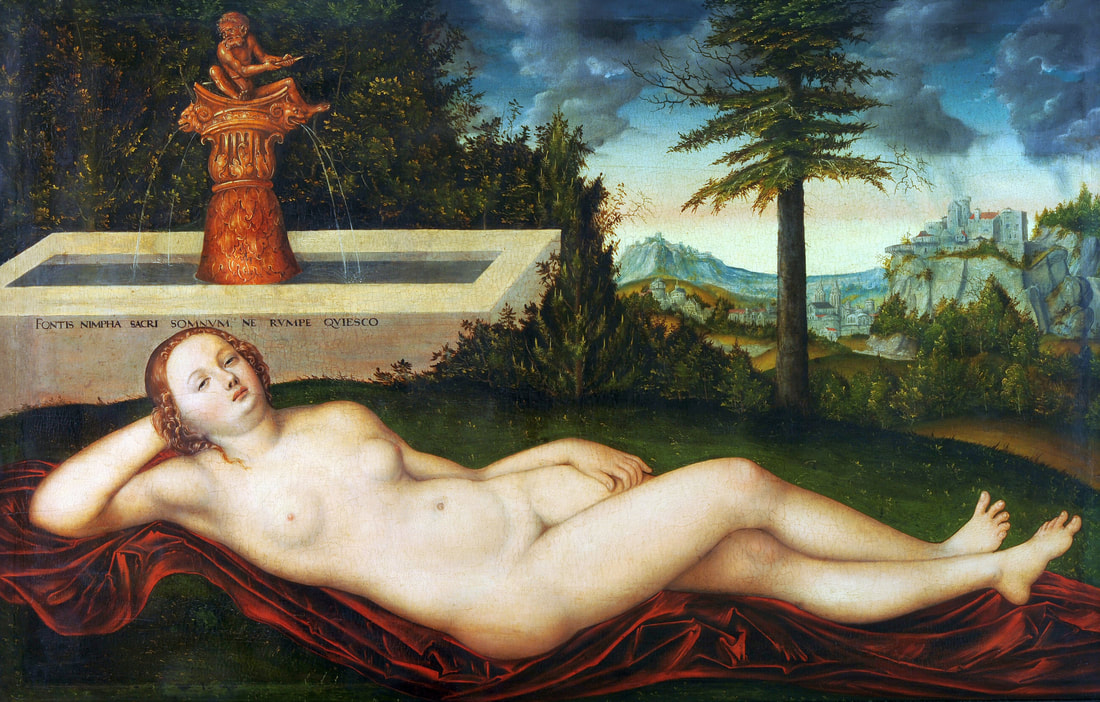

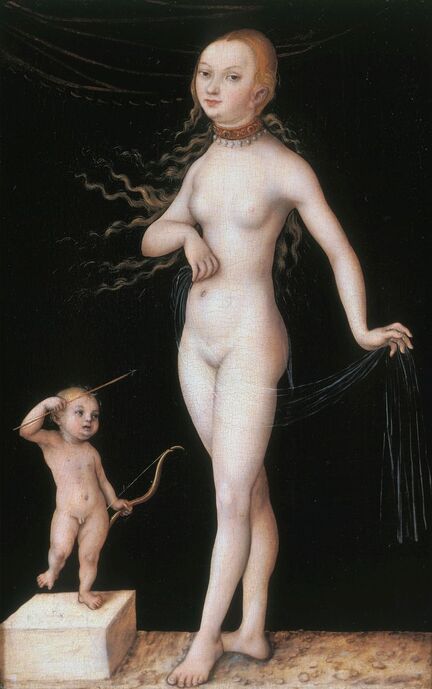

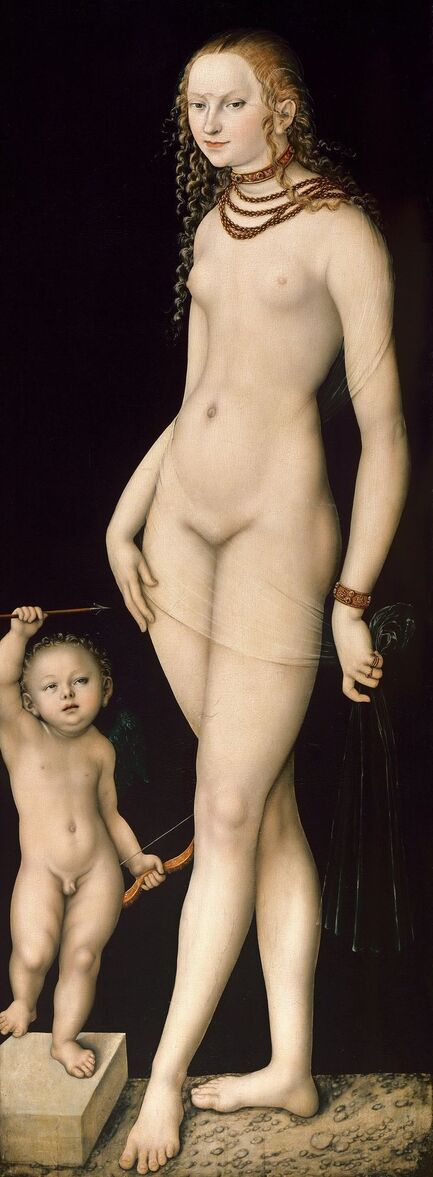

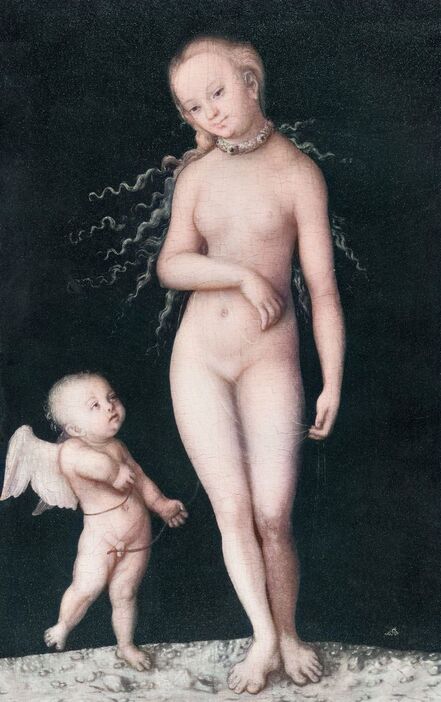

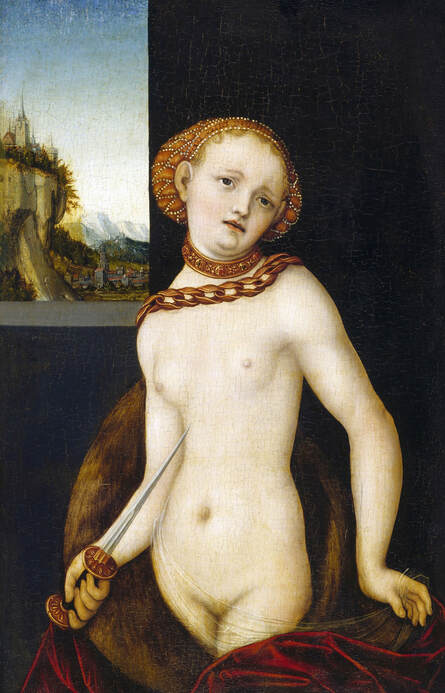

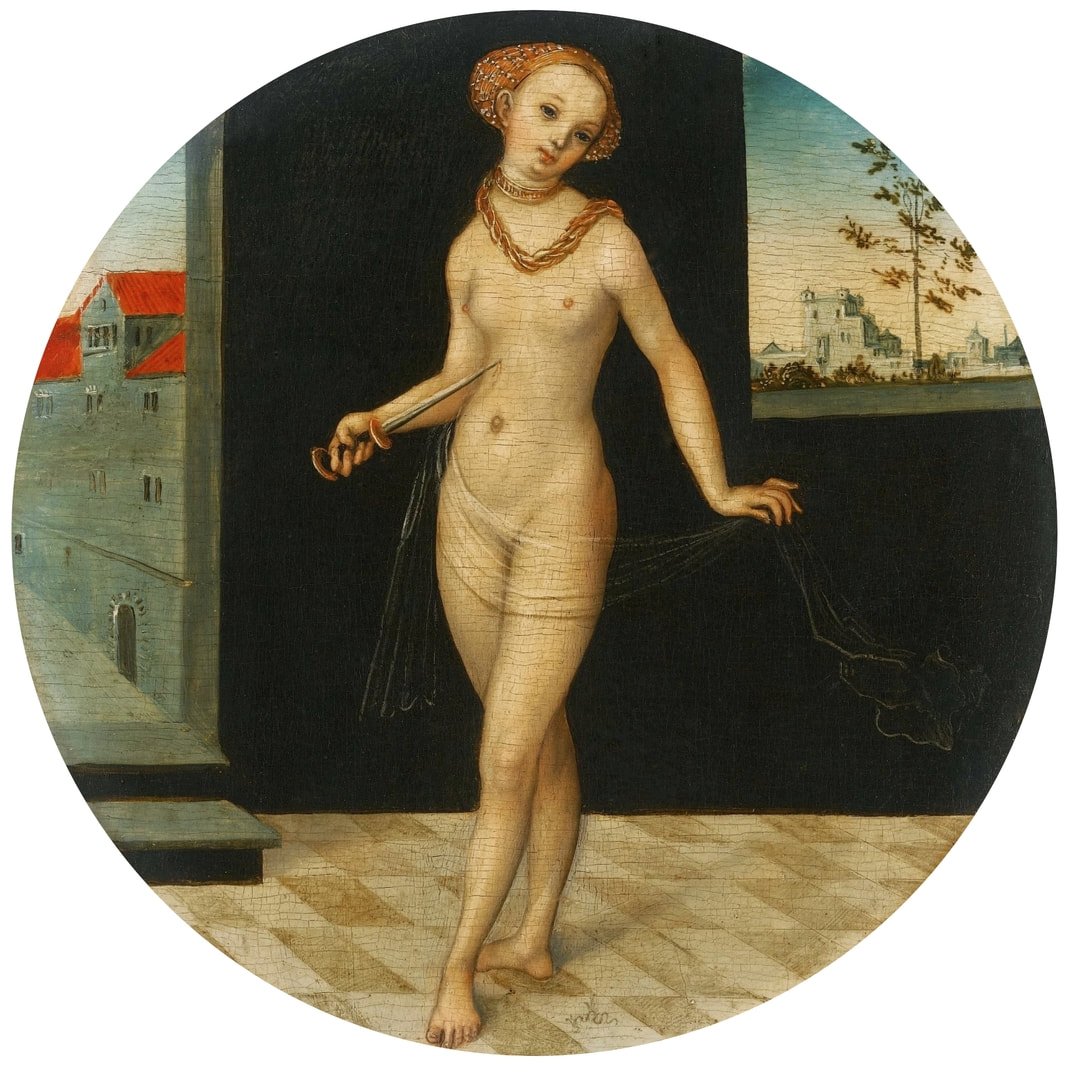

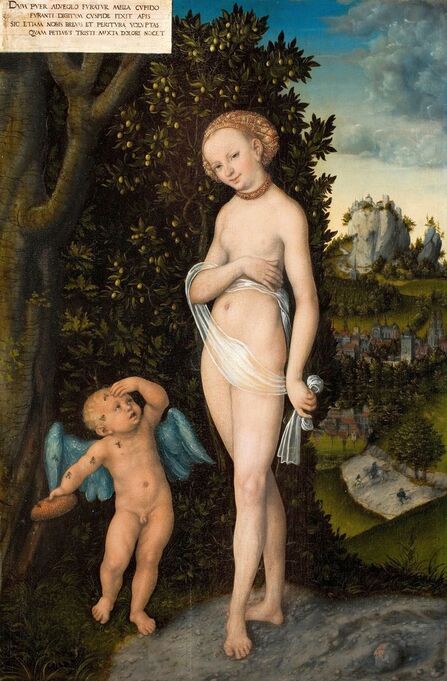

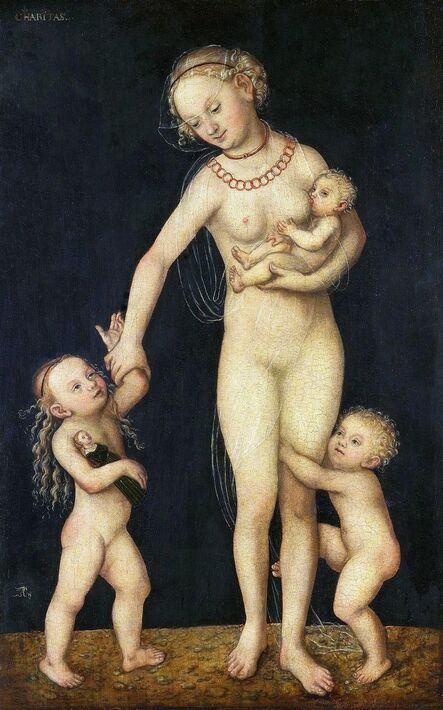

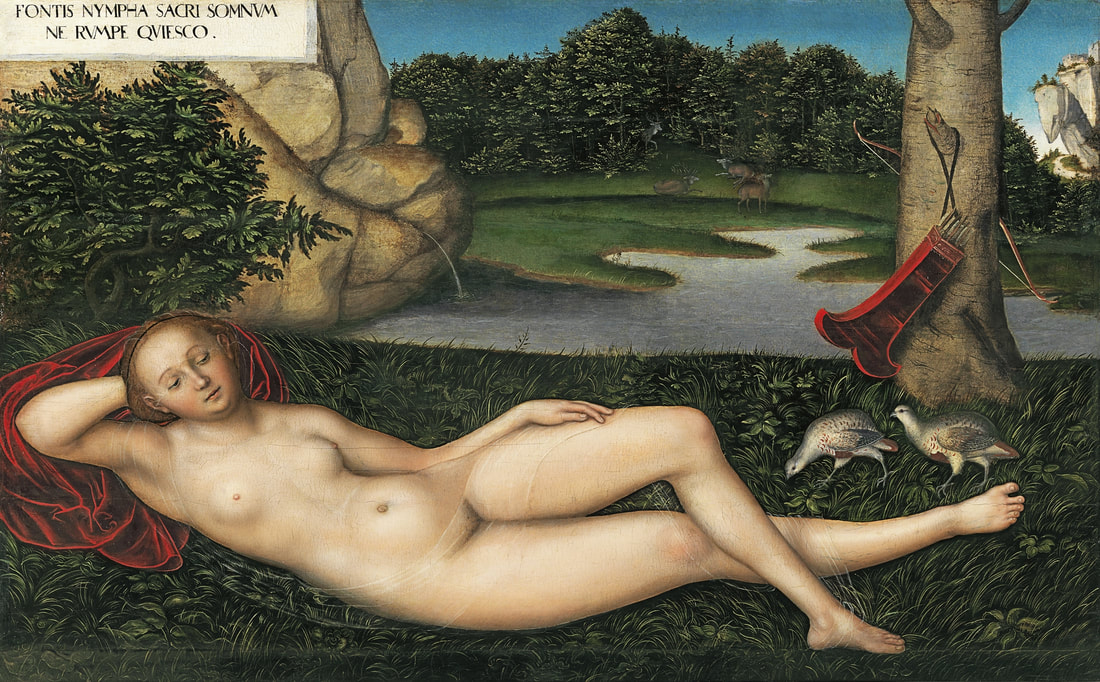

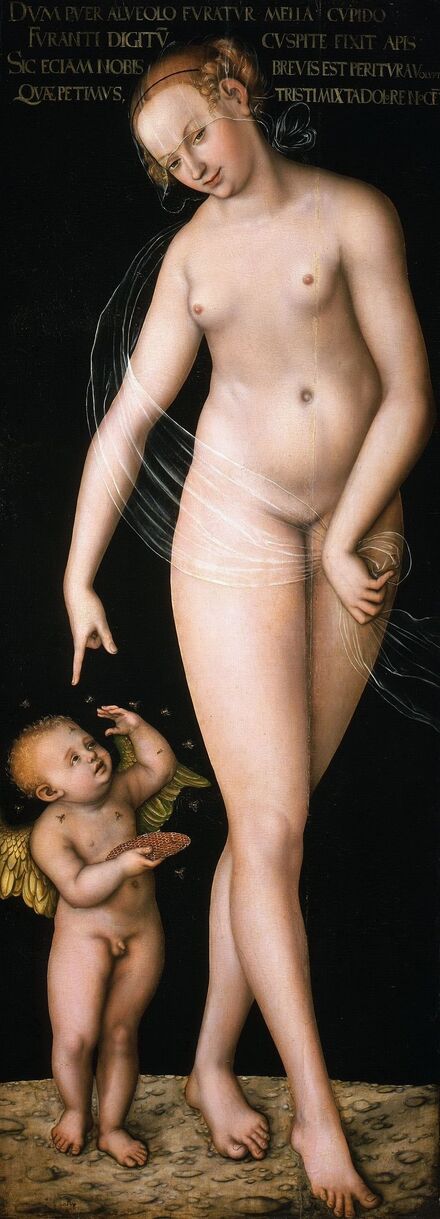

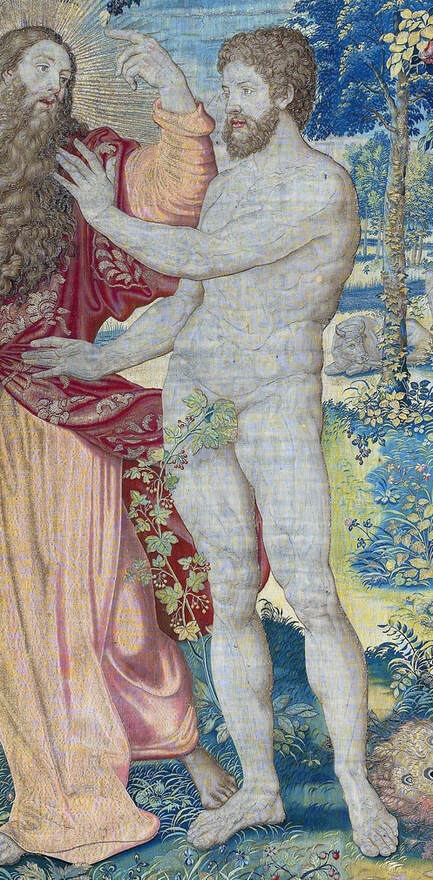

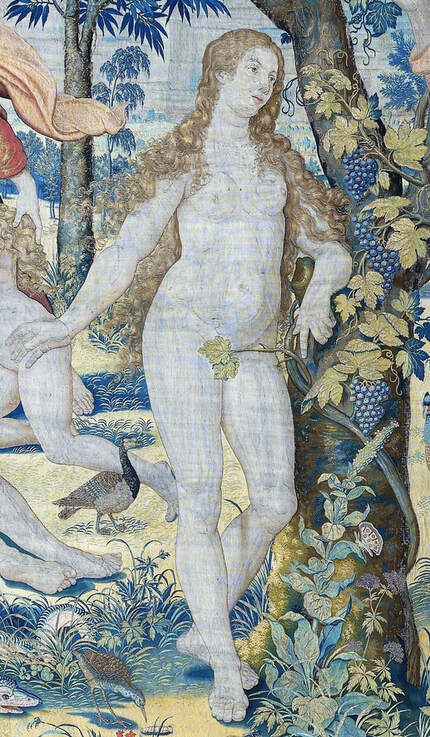

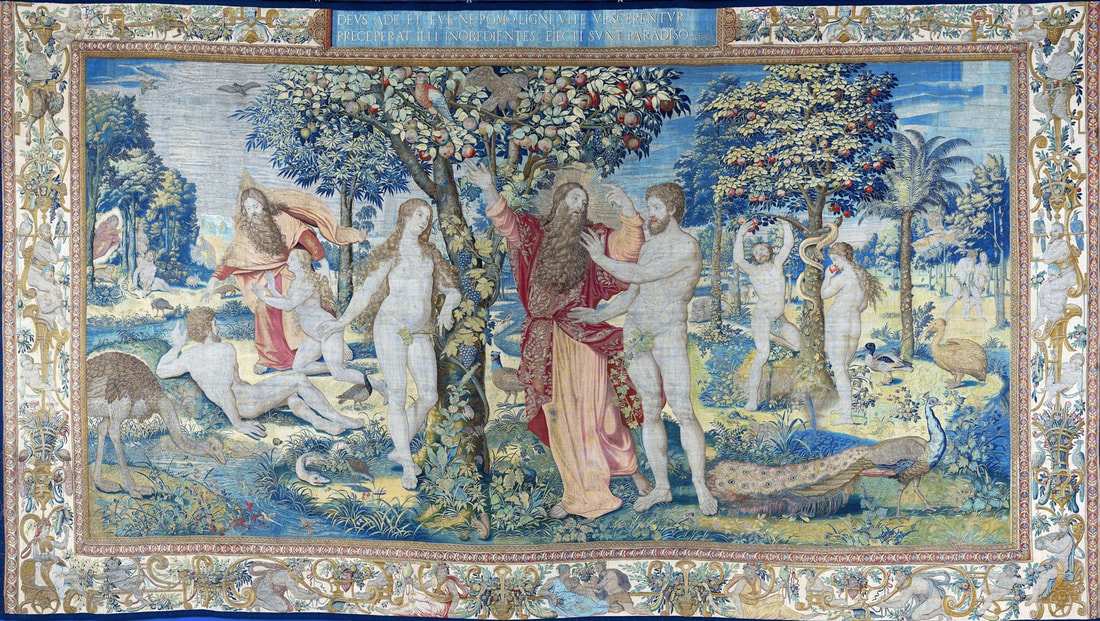

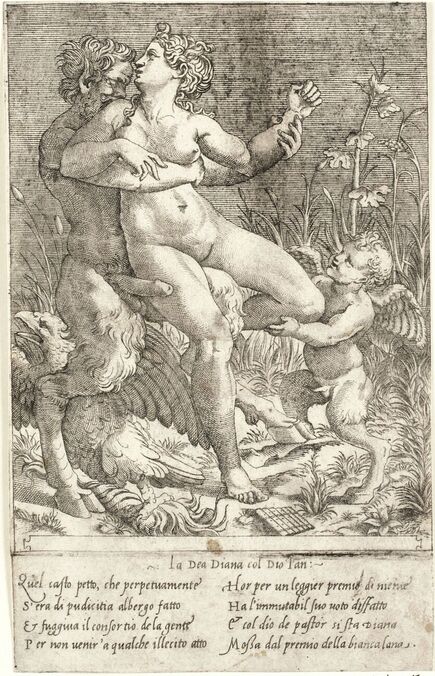

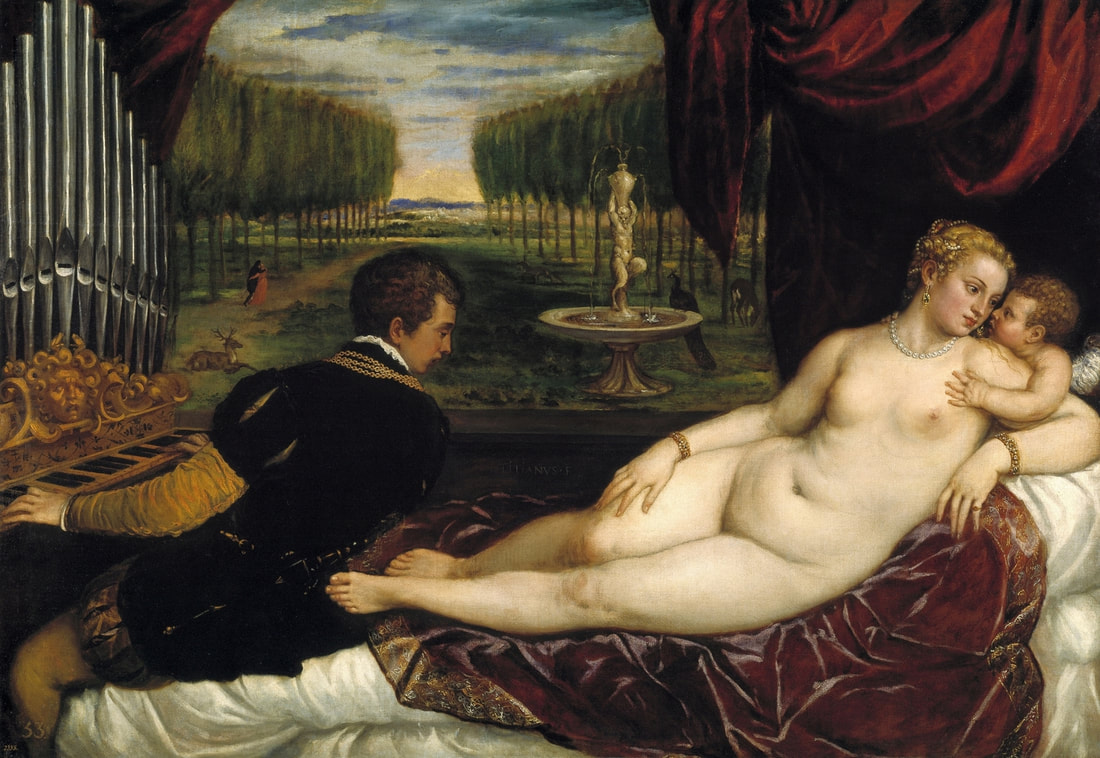

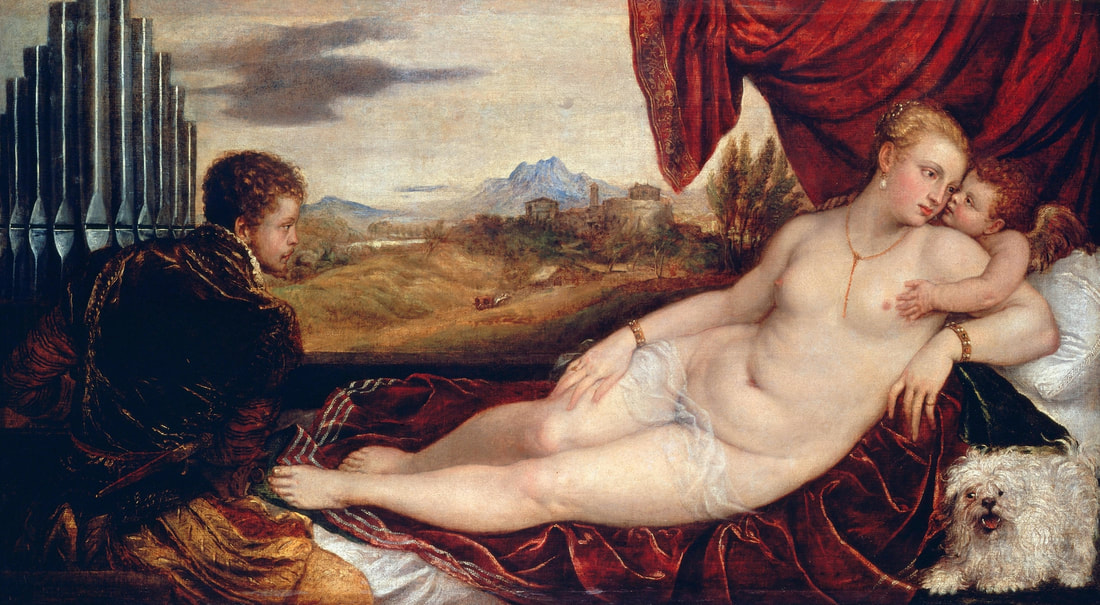

"Before the Deluge", it is a former title of a painting now identified to depict the Feast of the prodigal son. It was painted by Cornelis van Haarlem, a painter from the Protestant Netherlands, best known for his highly stylized works with Italianate nudes, in 1615, when the elected monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a descendant of the Jagiellons - Sigismund III Vasa. Despite huge losses in the collections of paintings, the oeuvre of Cornelis van Haarlem is represented significantly in one of the largest museums in Poland - the National Museum in Warsaw, the majority of which comes from old Polish collections (three from the collection of Wojciech Kolasiński: Adam and Eve, Mars and Venus as lovers, Vanitas and the Feast of the prodigal son from the collection of Tomasz Zieliński in Kielce).

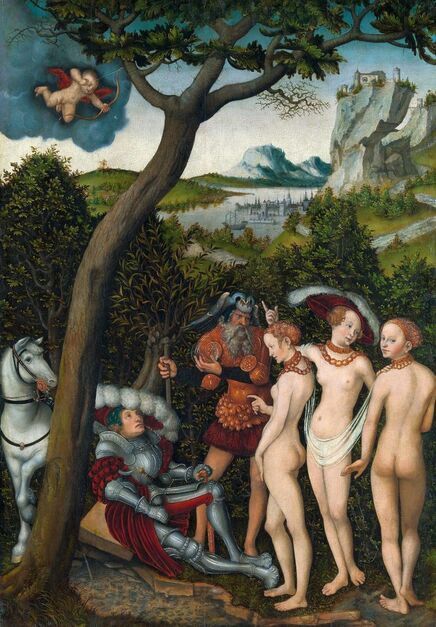

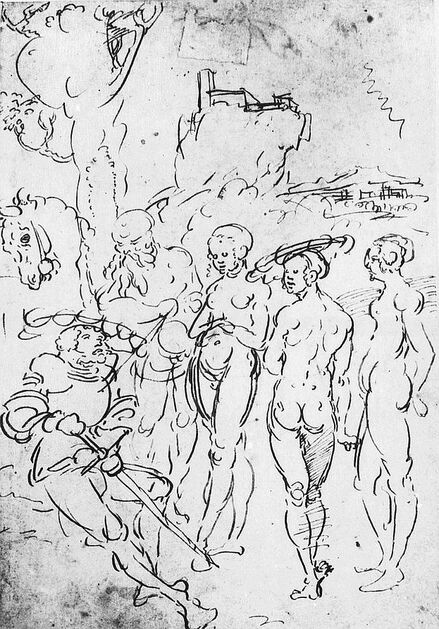

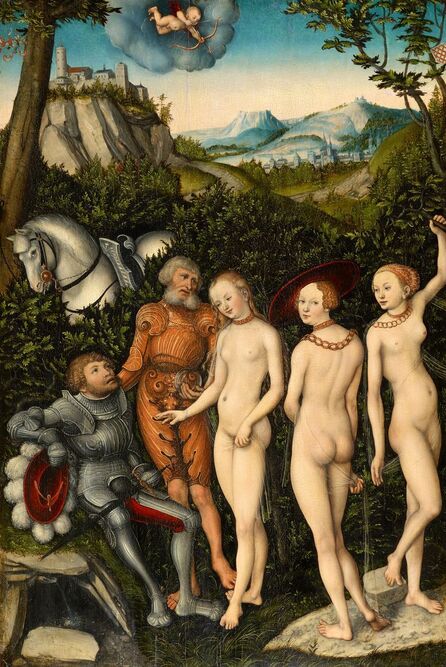

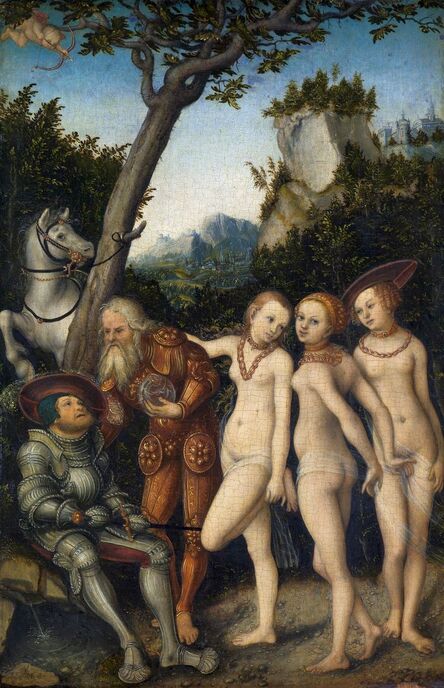

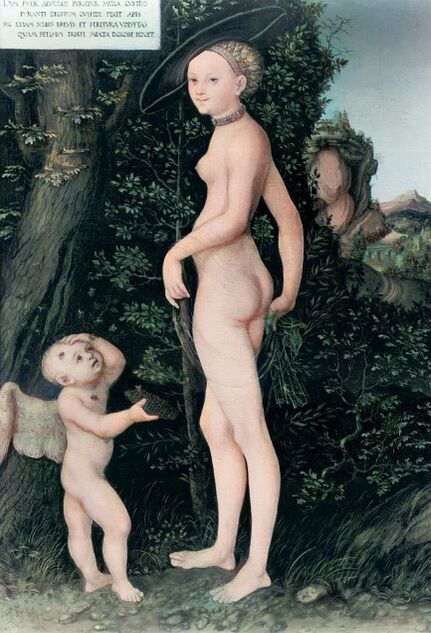

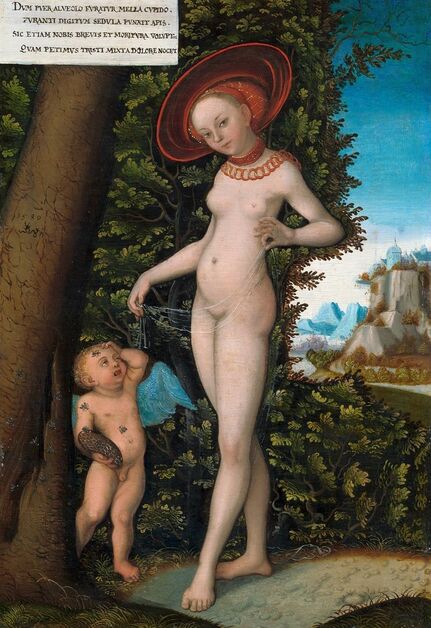

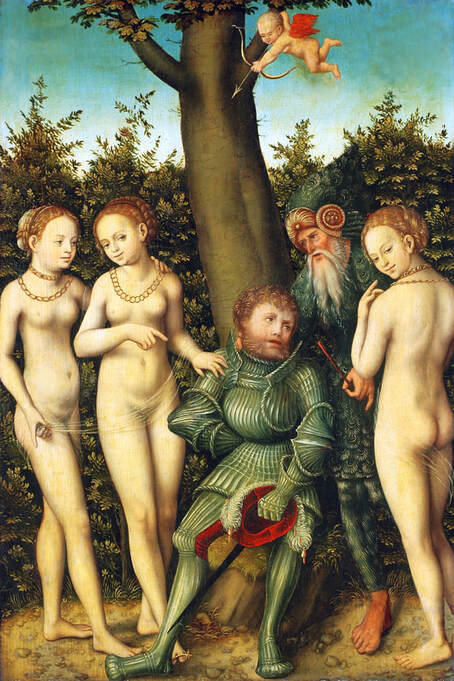

Sadly, its earlier history is unknown, so it cannot be unmistakably associated with the Golden Age of Poland-Lithuania, which, almost as in the Bible, ended with the Deluge (1655-1660), a punishment for sins as some might believe or like the opening of Pandora's box unleashing evil upon the world. "The Swedes and the notorious Germans, for whom murder is a play, the violation of faith is a joke, robbery a pleasure, arson, rape of women and all crimes a joy, our city, destroyed by numerous contributions, they destroyed with fire, leaving only the Koźmin suburb unburned", describes the atrocities in the city of Krotoszyn, burned down on July 5, 1656, an eyewitness - an altarist, brother Bartłomiej Gorczyński (after "Lebenserinnerungen" by Bar Loebel Monasch, Rafał Witkowski, p. 16). Descriptions of the destroyed Vilnius after the withdrawal of the Russian and Cossack armies, and other cities of the Most Serene Republic, are equally terrifying. Polish troops responded with similar ruthlessness, sometimes also towards their own citizens, who collaborated with the invaders or were accused of collaboration. The invasion was accompanied by epidemics related to the marches of various armies, destruction of the economy, exacerbation of conflicts and social and ethnic divisions. An unimaginable Apocalypse, sent not by God but by human greed. War should be a forgotten relic of the past, but unfortunately it is still not. Another painting in the National Museum in Warsaw recalls these events. This small painting (oil on copper, 29.6 x 37.4 cm, inventory number 34174) was very probably made by Christian Melich, court painter of the Polish-Lithuanian Vasas, active in Vilnius between 1604 and 1655 (similar in style to the Surrender of Mikhail Shein in the National Museum in Krakow, MNK I-12) or other Flemish painter. It was initially thought to represent King John II Casimir Vasa after the Battle of Berestechko in 1651, but the distinctive features of a man on horseback allowed to identify him with great certainty as Charles X Gustav the "Brigand of Europe", as he was called in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, "who was capable of beginning horrors of war in any part of the old continent" (after "Acta Universitatis Lodziensis: Folia historica", 2007, p. 56), and the subject as his triumph over the country. Female personifications of the Commonwealth, most likely Poland, Lithuania and Ruthenia (or Prussia) like three goddesses from the Judgement of Paris, pay homage to the "Brigand of Europe" supported by Mars and Minerva and trampling Polish enemies in national costumes. One of the women (Venus-Poland) offers the crown and a putto or Cupid offers the symbol of Poland, the White Eagle. Mars, with his sword drawn, looks at the humble woman. Dramatic events change not only individuals but also entire nations.

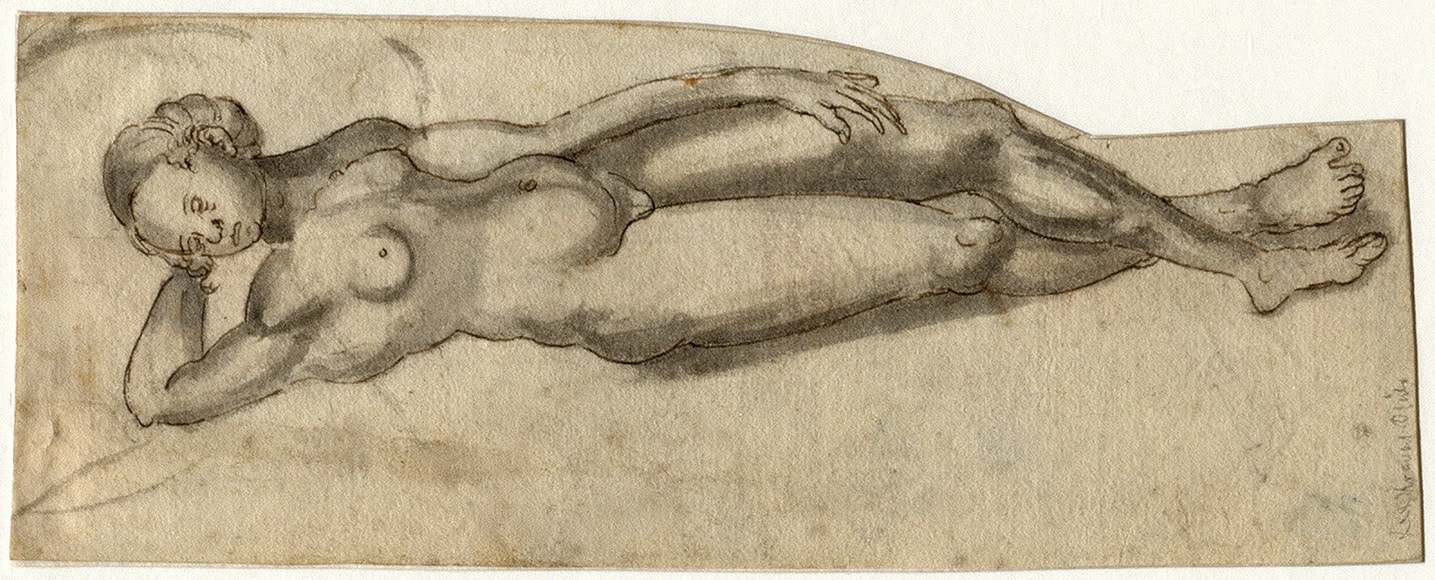

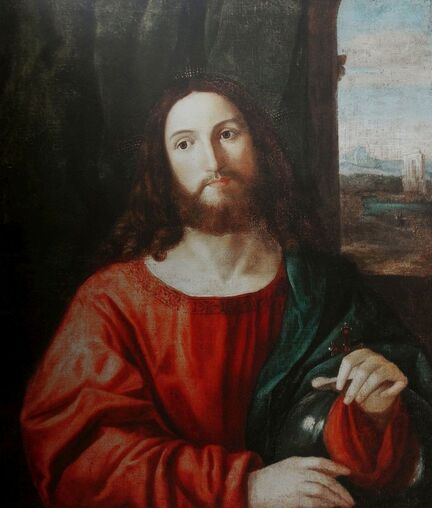

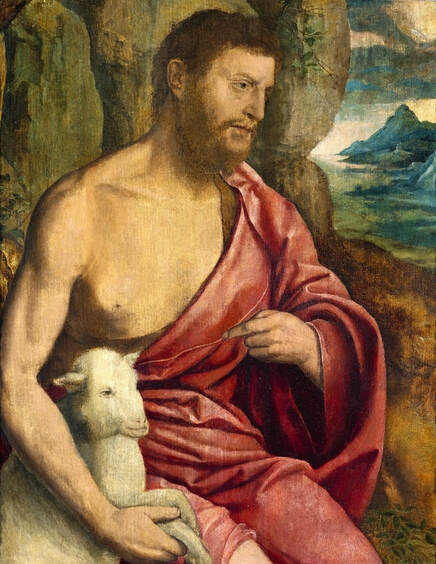

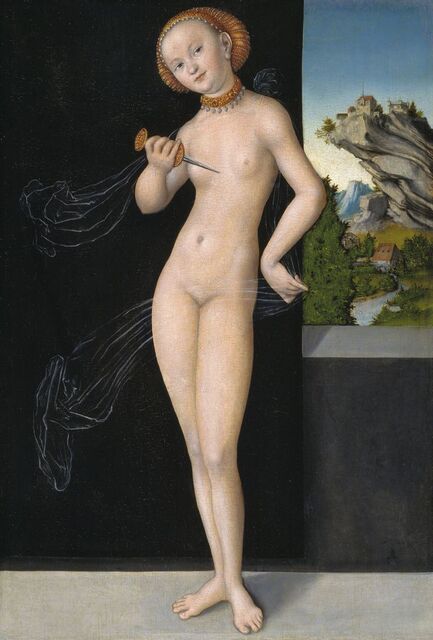

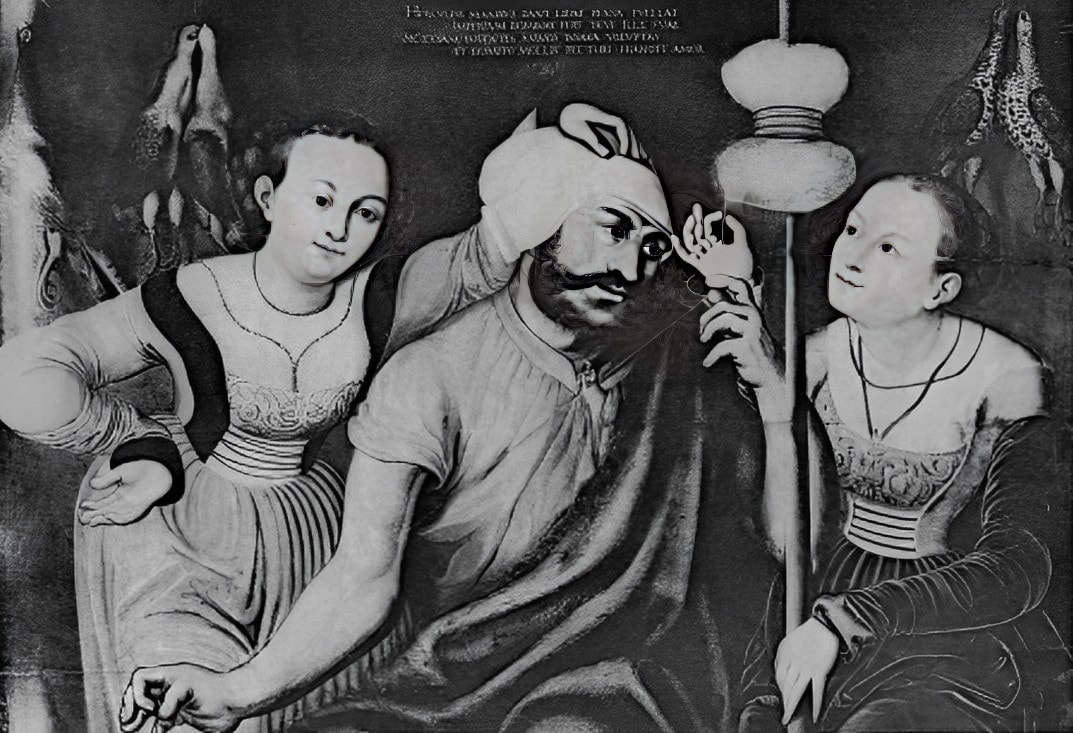

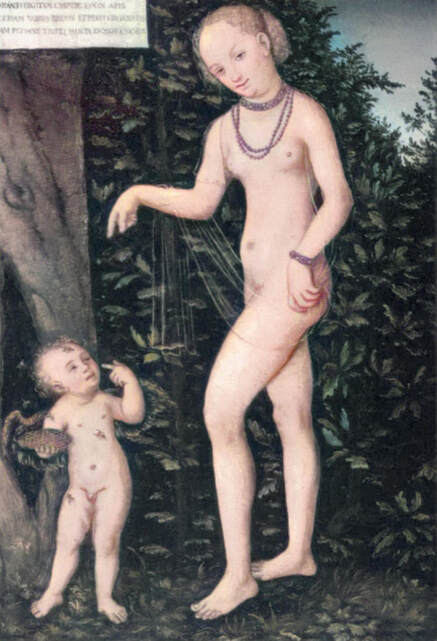

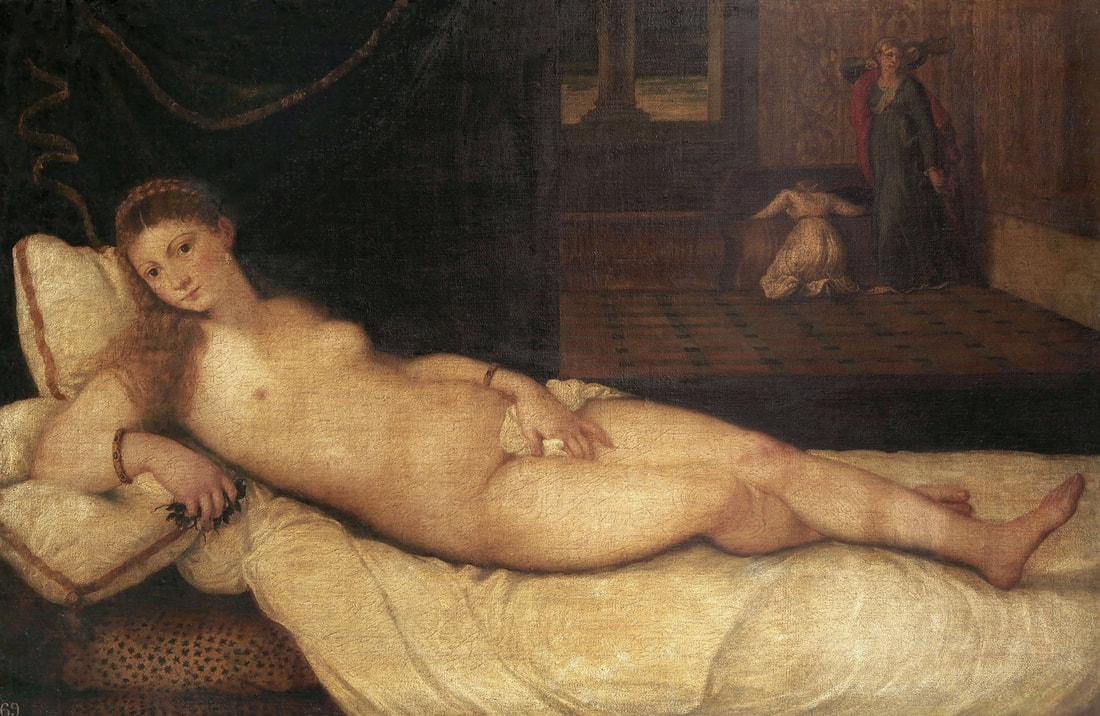

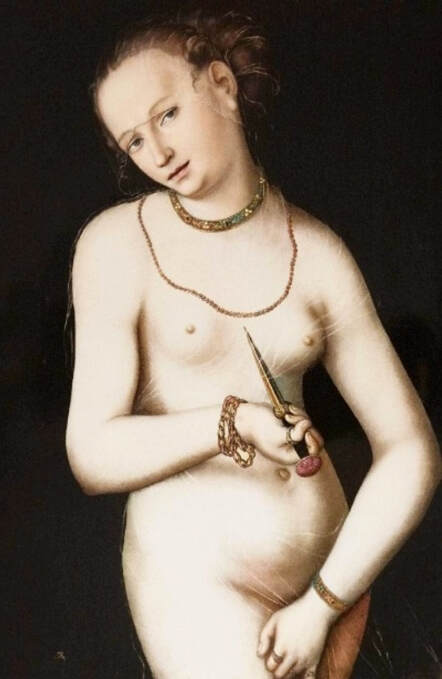

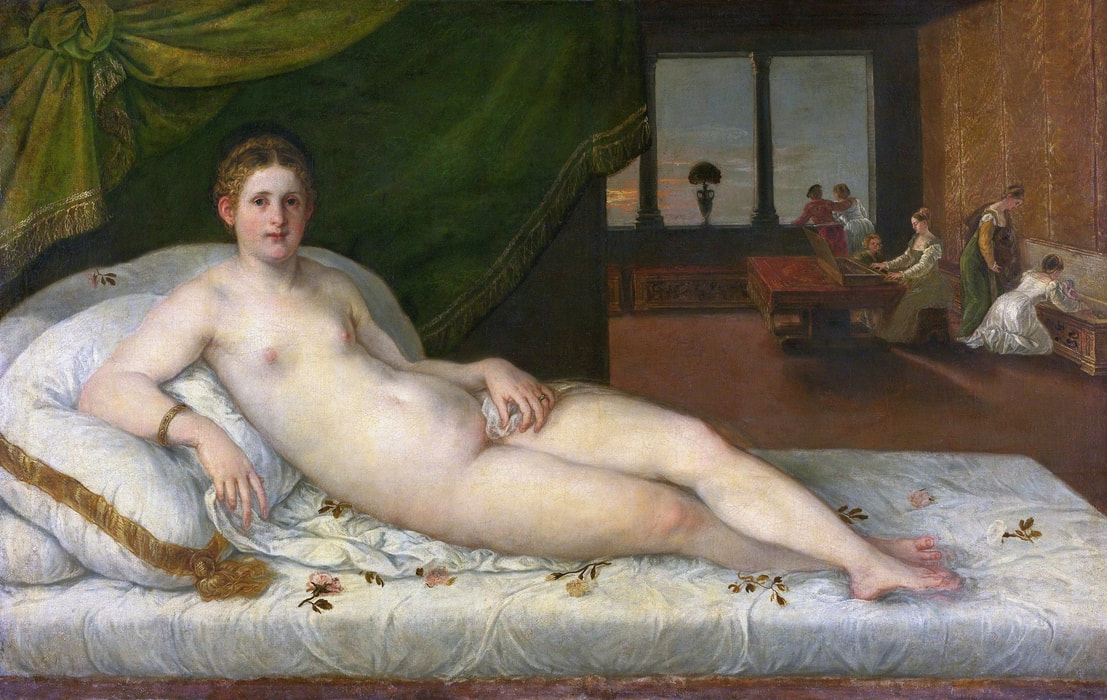

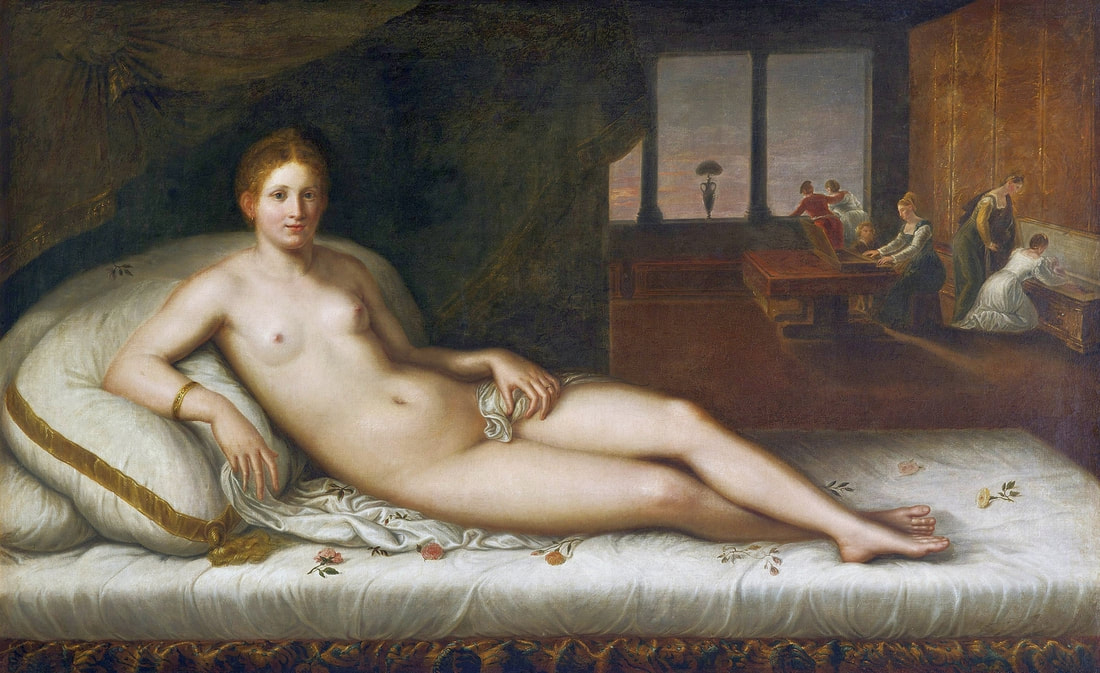

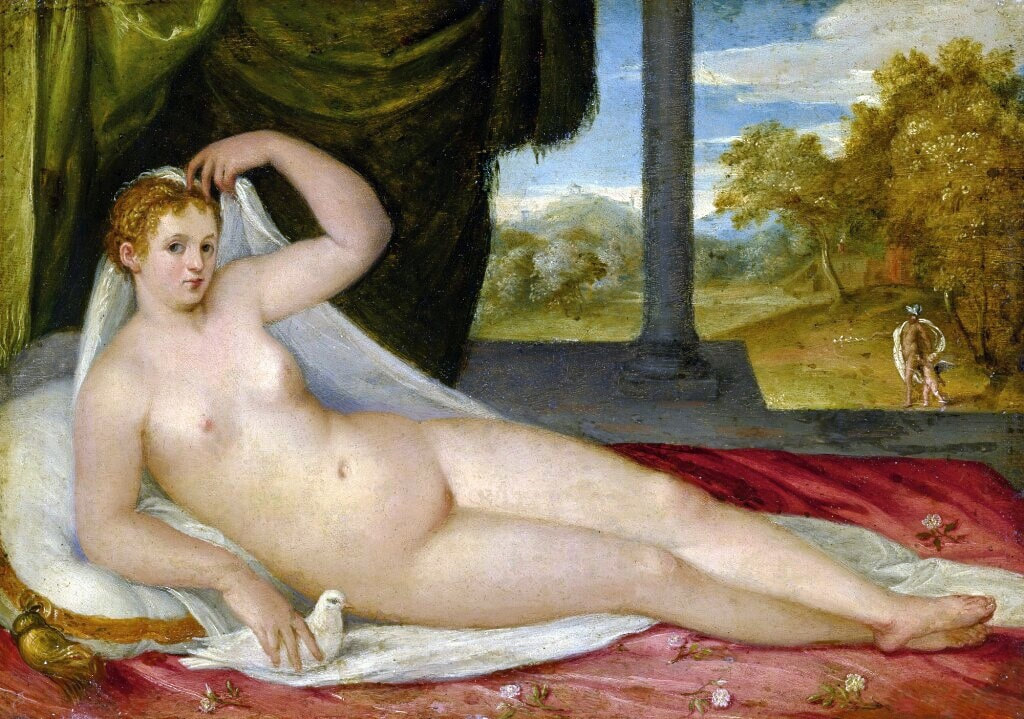

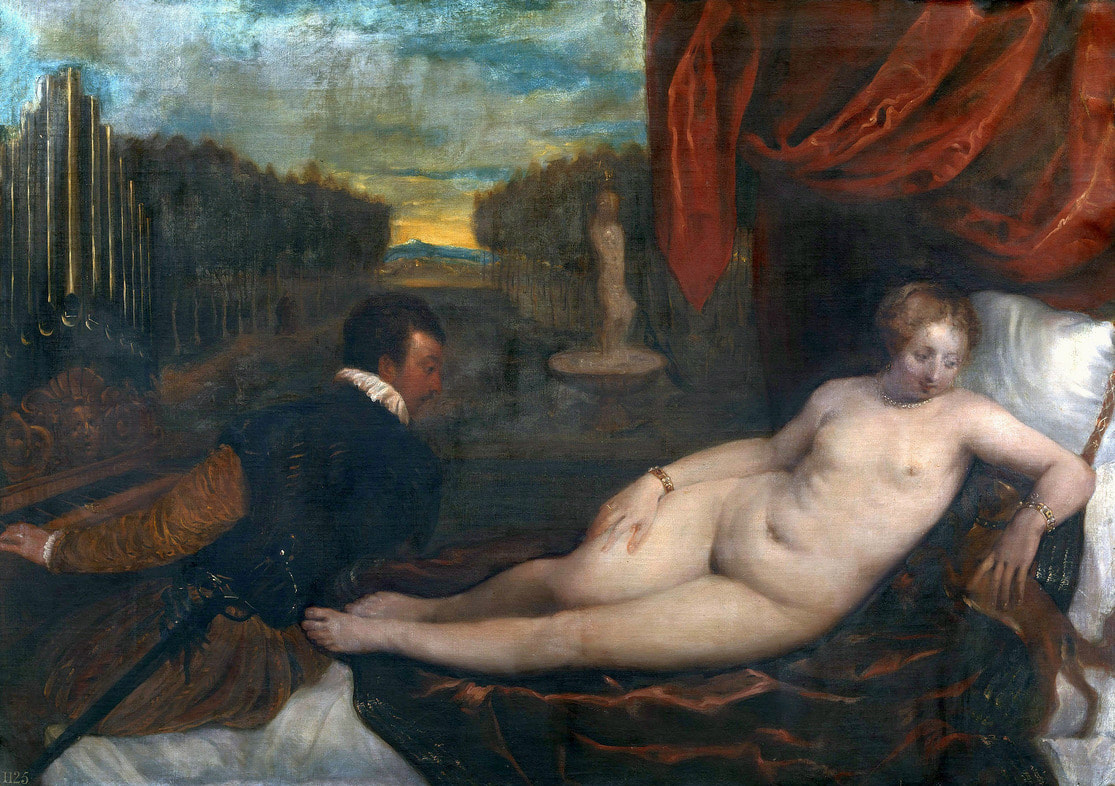

Mars and Venus as lovers (Mars being disarmed by Venus) by Cornelis van Haarlem, 1609, National Museum in Warsaw.

Feast of the prodigal son (Before the Deluge) by Cornelis van Haarlem, 1615, National Museum in Warsaw.

Triumph of Charles X Gustav the "Brigand of Europe" over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by Flemish painter, most probably Christian Melich, ca. 1655, National Museum in Warsaw.

Bibliography and legal notice. The majority of historical facts in the "Forgotten portraits" and information on works of art are easily verifiable on reliable sources available on the Internet, otherwise I invite you to visit the National Libraries of Poland - personally or virtually (Polona). The majority of translations, if not specifically attributed to someone else in the text or cited sources, are my authorship. Original paintings reproduced in "Forgotten portraits" are considered to be in the public domain (faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art, copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or fewer) in accordance with international copyright law (photos from publicly available photo libraries, websites of relevant institutions, my own photos and scans from various publications with credit to the owner), however, all have been retouched and enhanced without significant interference with the quality of the original artwork, where possible (Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported, CC BY-SA 3.0). All interpretations, identifications and attributions, not specifically attributed to other authors in the text or cited sources, must be considered as my authorship - Marcin Latka (Artinpl).

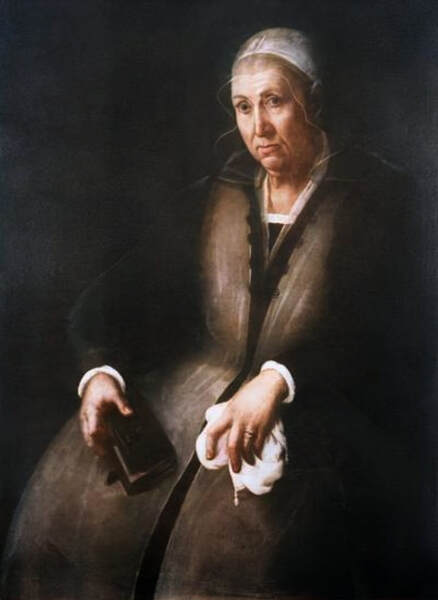

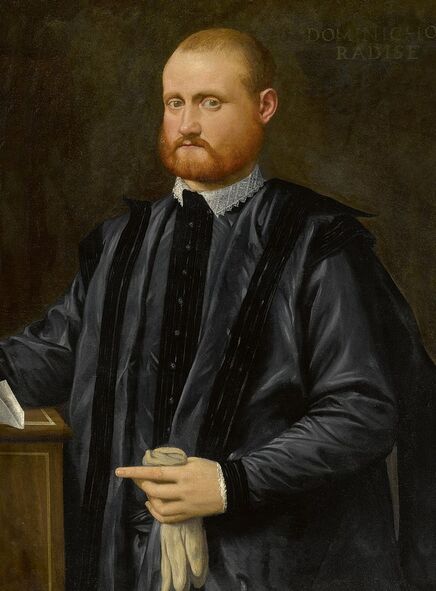

Majority of confirmed effigies of the Last Polish-Lithuanian Jagiellons are official, popular portraits pertaining to northern school of painting. As in some countries today, in the 16th century, people wanted a portrait of their monarch at home. Such effigies were frequently idealized, simplified and inscribed in Latin, which was the official language, apart from Ruthenian and Polish, of the multicultural country. They provided the official titulature (Rex, Regina), coat of arms and even age (ætatis suæ). Private and paintings dedicated to upper class were less so direct. Painters were operating with a complex set of symbols, which were clear then, however, are no longer so obvious today.

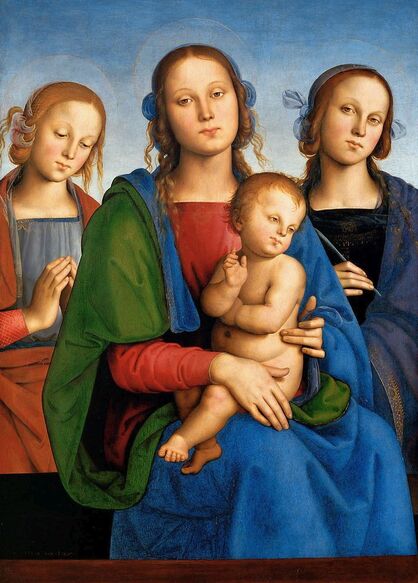

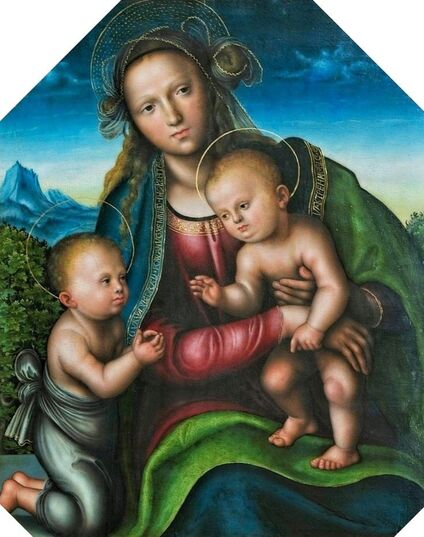

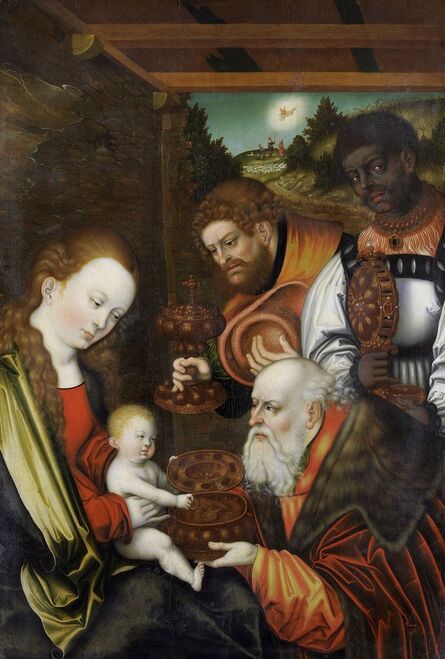

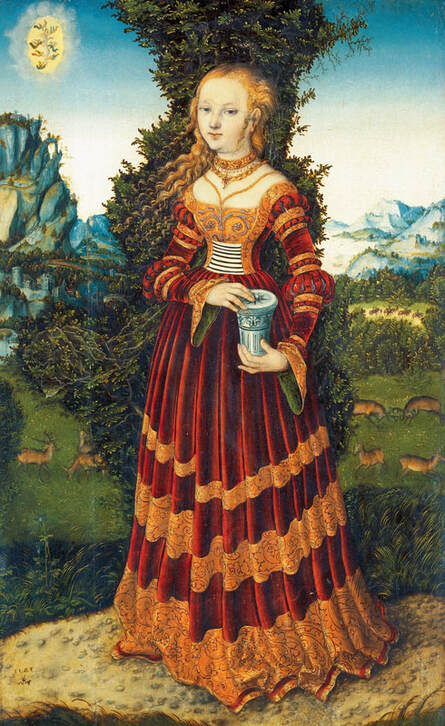

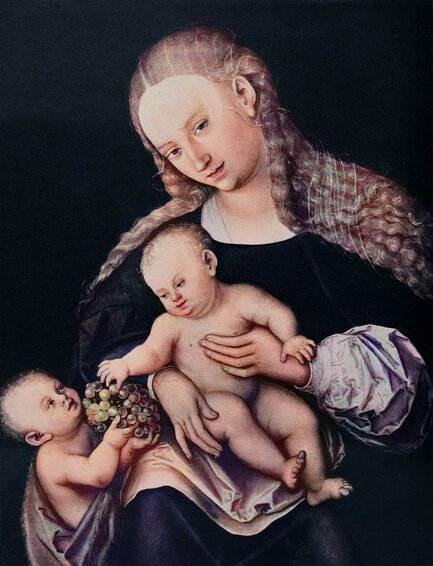

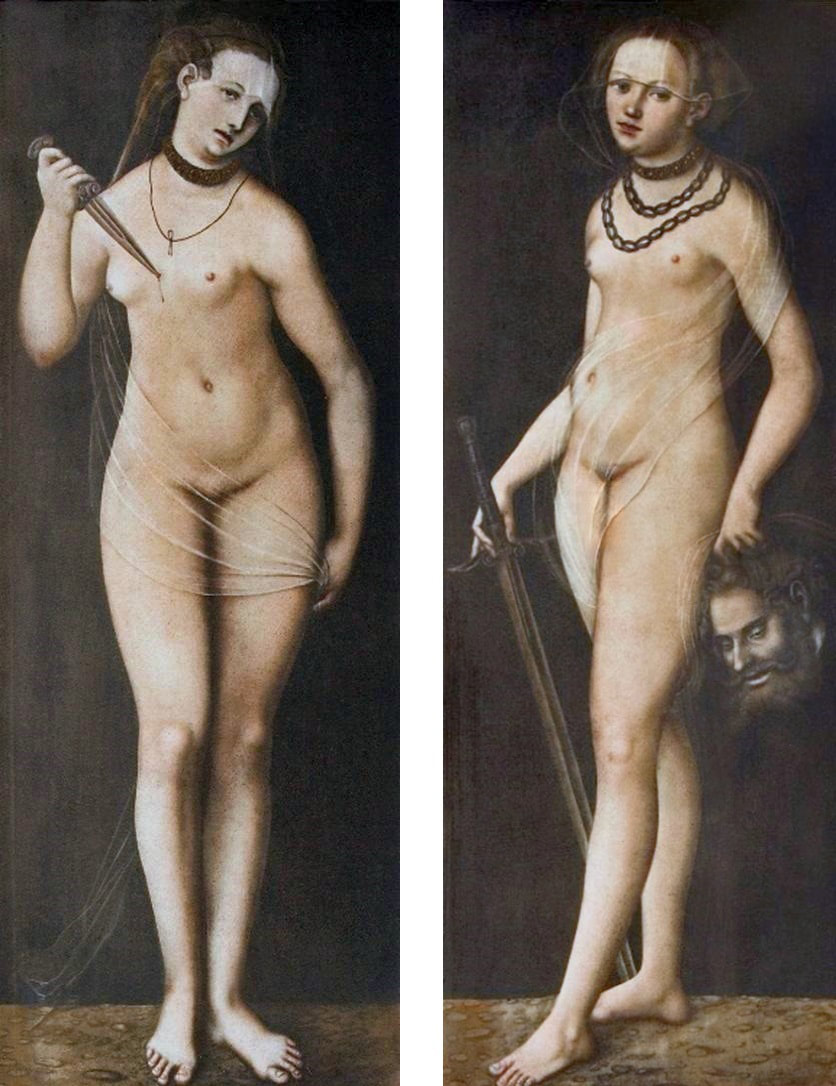

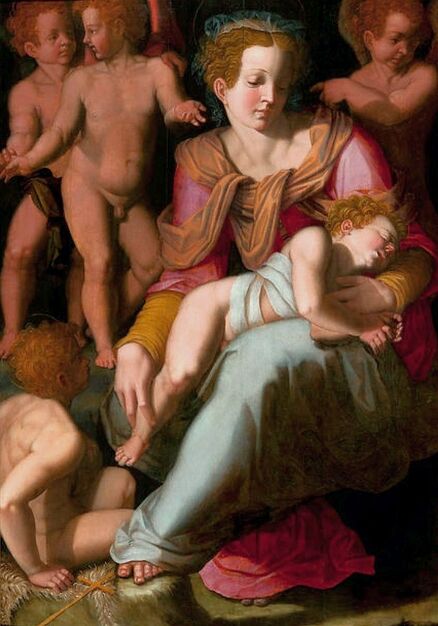

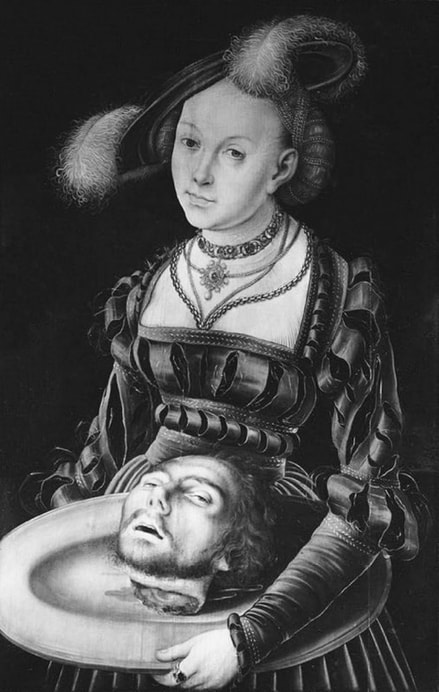

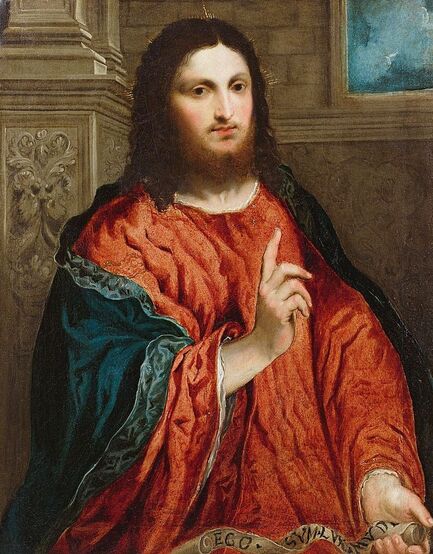

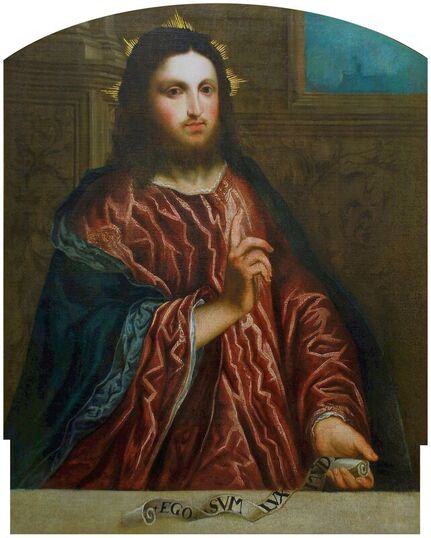

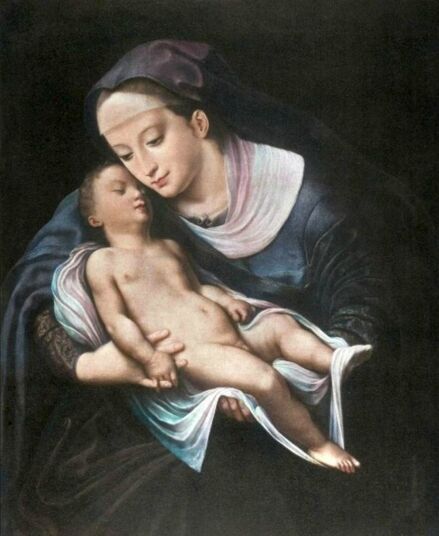

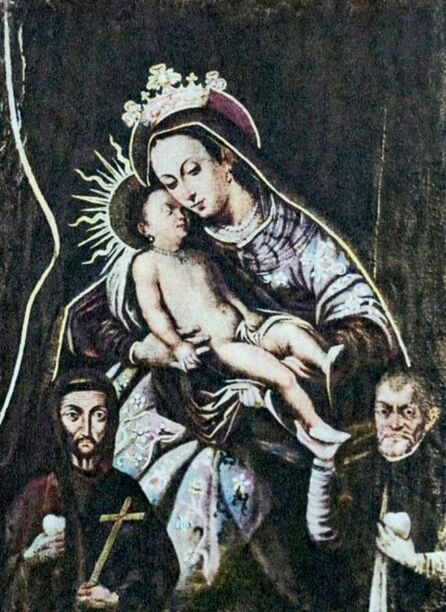

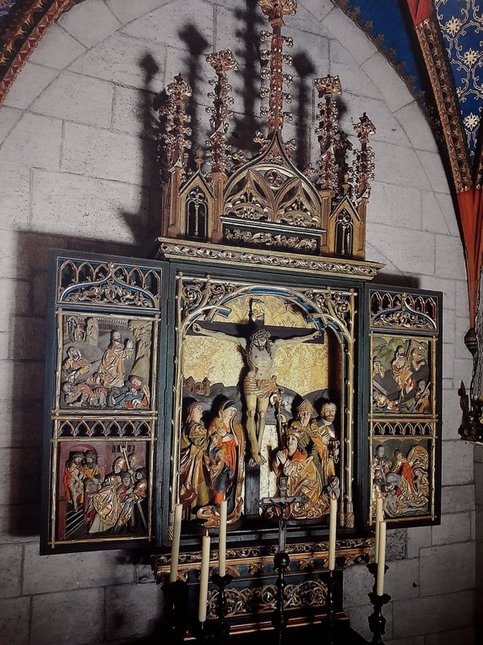

Since the very beginning of the Jagiellonian monarchy in Poland-Lithuania, art was characterized by syncretism and great diversity, which is best illustrated by the churches and chapels founded by the Jagiellons. They were built in a Gothic style with typical pointed arches and ribbed vaults and decorated with Russo-Byzantine frescoes, thus joining Western and Eastern traditions. Perhaps the oldest portraits of the first Jagiellonian monarch - Jogaila of Lithuania (Ladislaus II Jagiellon) are his effigies in the Gothic Holy Trinity Chapel at the Lublin Castle. They were commissioned by Jogaila and created by Ruthenian Master Andrey in 1418. On one, the king was represented as a knight on horseback and on the other as a donor kneeling before the Blessed Virgin Mary. The vault was adorned with the image of Christ Pantocrator above the coat of arms of the Jagiellons (Jagiellonian Cross). Similar church murals were created for Jogaila by the Orthodox priest Hayl around 1420 in the Gothic choir of Sandomierz Cathedral and for his son Casimir IV Jagiellon in the Holy Cross Chapel of the Wawel Cathedral by Pskov painters in 1470. Jogaila's portrait as one of the Magi in the mentioned Holy Cross Chapel (Adoration of the Magi, section of the Our Lady of Sorrows Triptych) is attributed to Stanisław Durink, whose father came from Silesia, and his marble tomb monument in the Wawel Cathedral to artists from Northern Italy. Perfectly conversant with Latin and the other languages of medieval and renaissance Europe, Poles, Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Germans and other ethnic groups of the multi-ethnic country, traveled to different countries of Western Europe, thus various fashions, even the strangest ones, like the effigies of Christ with Three Faces or effigies of crucified, bearded female Saint Wilgefortis, easily penetrated Poland-Lithuania. Disguised portraits, especially likenesses in guise of the Virgin Mary were popular in different parts of Europe from at least the mid-15th century (e.g. portraits of Agnès Sorel, Bianca Maria Visconti and Lucrezia Buti). Often unpopular rulers and their wives or mistresses were depicted as members of the Holy Family or saints. This naturally led to frustration and sometimes the only possible response was satire. The diptych by anonymous Flemish painter, most likely Marinus van Reymerswaele, from the 1520s (Wittert Museum in Liège, inventory number 12013), referring to diptychs by Hans Memling, Michel Sittow, Jehan Bellegambe, Jan Provoost, Jan Gossaert and other painters is obviously a satirical criticism of these representations. Instead of the rosy cheeks of a "virgin" holding a red carnation flower, a symbol of love and passion, the curious viewer will see brown cheeks and a thistle, a symbol of earthly pain and sin. In a 1487 diptych of Hieronymus Tscheckenburlin by the German painter, the rosy virgin is replaced by a rotting skeleton - memento mori (Kunstmuseum Basel). Sometimes also, historical scenes were represented in a mythological or biblical disguise or in a fantastic entourage. This is the case of a painting depicting the Siege of Malbork Castle in 1454 seen from the west - one of four paintings by Martin Schoninck, commissioned around 1536 by the Malbork Brotherhood to hang above the Brotherhood bench in the Artus Court in Gdańsk. To emphasize the victory of Gdańsk and the Jagiellonian monarchy over the Teutonic Order, the painting is accompanied by the Story of Judith, a mere woman, who overcomes a superior enemy, and effigies of Christ Salvator Mundi and Madonna and Child (lost during World War II). The widespread popularity of the "Metamorphoses" and other works of the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17/18 AD) also contributed to the popularity of disguised portraits. The poet lived among the Sarmatians, legendary ancestors of the nobles of Poland-Lithuania, and was therefore considered the first national poet (compare "Ovidius inter Sarmatas" by Barbara Hryszko, p. 453, 455). In the "Metamorphoses" he deals with transformation into different beings, disguise, illusion and deception, as well as the deification of Julius Caesar and Augustus since both leaders trace their lineage through Aeneas to Venus, who "struck her breast with both hands, and tried to hide Caesar in a cloud" in an attempt to rescue him from the conspirators' swords. Poland-Lithuania was the most tolerant country of Renaissance Europe, where in the early years of the Reformation many churches simultaneously served as Protestant and Catholic temples. There are no known sources regarding organized iconoclasm, known from western Europe, in most cases works of art were sold, when churches were completely taken over by the Reformed denominations. Disputes over the nature of the images remained mainly on paper - the Calvinist preacher Stanisław Lutomirski called the Jasna Góra icon of the Black Madonna "an idolatry table", "a board from Częstochowa" that made up the doors of hell, and he described worshiping it as adultery and Jakub Wujek refuted the charges of iconoclasts, saying that "having thrown away the images of the Lord Christ, they replace them with images of Luther, Calvin and their harlots" (after "Ikonoklazm staropolski" by Konrad Morawski). Unlike other countries where effigies of "The Fallen Madonna with the Big Boobies", nude or half-naked images of saints or disguised portraits in churches and public places were destroyed in mob actions by Protestant crowds, in Poland-Lithuania such incidents were rare. Before the Great Iconoclasm, many temples were filled with nudity and so-called falsum dogma appearing at the time of the the Council of Trent (twenty-fifth session of the Tridentium, on December 3 and 4, 1563), which "means not so much a heretical view, but a lack of orthodoxy from the Catholic point of view. Iconography was to be cleansed of such errors as lewdness (lascivia), superstition (superstitio), shameless charm (procax venustas), and finally disorder and thoughtlessness" (after "O świętych obrazach" by Michał Rożek). The "divine nakedness" of ancient Rome and Greece, rediscovered by the Renaissance, was banished from churches, however many beautiful works of art preserved - like naked Crucifixes by Filippo Brunelleschi (1410-1415, Santa Maria Novella in Florence), by Michelangelo (1492, Church of Santo Spirito in Florence and another from about 1495, Bargello Museum in Florence) and by Benvenuto Cellini (1559-1562, Basilica of Escorial near Madrid). Nudity in Michelangelo's Last Judgment (1536-1541, Sistine Chapel) was censored the year after the artist's death, in 1565 (after "Michelangelo's Last Judgment - uncensored" by Giovanni Garcia-Fenech). In this fresco nearly everyone is naked or seminaked. Daniele da Volterra painted over the more controversial nudity of mainly muscular naked male bodies (Michelangelo's women look more like men with breasts, as the artist had spent too much time with men to understand the female form), earning Daniele the nickname Il Braghettone, "the breeches-maker". He spared some female effigies and obviously homosexual scenes among the Righteous Men (two young men kissing and a young man kissing an old man's beard and two naked young men in a passionate kiss). The provisions of Trent reached Poland through administrative ordinances and they were accepted at the provincial synod in Piotrków in 1577. Diocesan synod of Kraków, convened by Bishop Marcin Szyszkowski in 1621, dealt with issues of sacred art. The resolutions of the synod were an unprecedented event in the artistic culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Published in Chapter LI (51) entitled "On sacred images" (De sacris imaginibus) of Reformationes generales ad clerum et populum ..., they created guidelines for the iconographic canon of sacred art. Holy images could not have portrait features, pictures of the naked Adam and Eve, Saint Mary Magdalene half-naked or embracing a cross in an obscene and multi-colored outfit, Saint Anne with three husbands, Virgin Mary painted or carved in too profane, foreign and indecent clothing should be removed from temples, because they contain false dogma, give the simple people an opportunity to fall into dangerous errors or are contrary to Scripture. However, the bans were not overly respected, because representations of the Holy Family, numbering more than twenty people, including Christ's siblings, have been preserved in the vast diocese of Kraków (after "O świętych obrazach" by Michał Rożek). The victorious Counter-Reformation and the victorious Reformation opposed shameless lust and shameless charm and a kind of paganism (after "Barok: epoka przeciwieństw" by Janusz Pelc, p. 186), but church officials could not ban "divine nakedness" from lay homes, and nude effigies of saints were still popular after the Council of Trent. Many of such paintings were acquired by clients from the Commonwealth abroad, in the Netherlands, in Venice and Rome, like, most likely, the Busty Madonna by Carlo Saraceni from the Krosnowski collection (National Museum in Warsaw, M.Ob.1605 MNW). It was the time of high infant and maternal mortality, less developed medicine, lack of public health care, when wars and epidemics ravaged large parts of Europe. Therefore, virility and fertility were considered by many to be a sign of God's blessing (after "Male Reproductive Dysfunction", ed. Fouad R. Kandeel, p. 6). In 1565 Flavio Ruggieri from Bologna, who accompanied Giovanni Francesco Commendone, a legate of Pope Pius IV in Poland, described the country in the manuscript preserved in the Vatican Library (Ex codice Vatic. inter Ottobon. 3175, Nr. 36): "Poland is quite well inhabited, especially Masovia, in other parts there are also dense towns and villages, but all wooden, counting up to 90,000 of them in total, one half of which belongs to the king, the other half to the nobility and clergy, the inhabitants apart from the nobility are a half and a quarter million, that is, two and a half million peasants and a million townspeople. [...] Even the craftsmen speak Latin, and it is not difficult to learn this language, because in every city, in almost every village there is a public school. They take over the customs and language of foreign nations with unspeakable ease, and of all transalpine countries, they learn the customs and the Italian language the most, which is very much used and liked by them as well as the Italian costume, namely at court. The national costume is almost the same as the Hungarian, but they like to dress up differently, they change robes often, they even change up several times a day. Since Queen Bona of the House of Sforza, the mother of the present king, introduced the language, clothes and many other Italian customs, some lords began to build in the cities of Lesser Poland and Masovia. The nobility is very rich. [...] Only townspeople, Jews, Armenians, and foreigners, Germans and Italians trade. The nobility only sells their own grain, which is the country's greatest wealth. Floated into the Vistula by the rivers flowing into it, it goes along the Vistula to Gdańsk, where it is deposited in intentionally built granaries in a separate part of the city, where the guard does not allow anyone to enter at night. Polish grain feeds almost all of King Philip's Netherlands, even Portuguese and other countries' ships come to Gdańsk for Polish grain, where you will sometimes see 400 and 500 of them, not without surprise. The Lithuanian grain goes along the Neman to the Baltic Sea. The Podolian grain, which, as has been said, perishes miserably, could be floated down the Dniester to the Black Sea, and from there to Constantinople and Venice, which is now being thought of according to the plan given by the Cardinal Kommendoni [Venetian Giovanni Francesco Commendone]. Apart from grain, Poland supplies other countries with flax, hemp, beef hides, honey, wax, tar, potash, amber, wood for shipbuilding, wool, cattle, horses, sheep, beer and some dyer's herb. From other countries they imports costly blue silks, cloth, linen, rugs, carpets, from the east precious stones and jewels, from Moscow, sables, lynxes, bears, ermines and other furs that are absent in Poland, or not as much as their inhabitants need to protect them from cold or for glamor. [...] The king deliberate on all important matters with the senate, although he has a firm voice, the nobility, as it has been said, has so tightened his power that he has little left over it" (after "Relacye nuncyuszow apostolskich ..." by Erazm Rykaczewski, pp. 125, 128, 131, 132, 136). Marcin Kromer (1512-1589), Prince-Bishop of Warmia, in his "Poland or About the Geography, Population, Customs, Offices, and Public Matters of the Polish Kingdom in Two Volumes" (Polonia sive de situ, populis, moribus, magistratibus et Republica regni Polonici libri duo), first published in Cologne in 1577, emphasized that "In almost our time, Italian merchants and craftsmen also reached the more important cities; moreover, the Italian language is heard from time to time from the mouths of more educated Poles, because they like to travel to Italy". He also stated that that "even in the very center of Italy it would be difficult to find such a multitude of people of all kinds with whom one could communicate in Latin" and as for the political system, he added that "the Republic of Poland is not much different […] from the contemporary Republic of Venice" (after "W podróży po Europie" by Wojciech Tygielski, Anna Kalinowska, p. 470). Mikołaj Chwałowic (d. 1400), called the Devil of Venice, a nobleman of Nałęcz coat of arms, mentioned as Nicolaus heres de Wenacia in 1390, is said to have named his estate near Żnin and Biskupin where he built a magnificent castle - Wenecja (Wenacia, Veneciae, Wanaczia, Weneczya, Venecia), after returning from his studies in the "Queen of the Adriatic". The country was formed by two major states - the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but it was a multiethnic and multicultural country with a large Italian community in many cities. The locals most often called it in Latin simply Res Publicae (Republic, Commonwealth) or Sarmatia (as the Greeks, Romans and Byzantines of Late Antiquity called the great territories of Central Europe), more literary and by nobility. Nationality was not considered in today's terms and was rather fluid, as in the case of Stanisław Orzechowski, who calls himself either Ruthenian (Ruthenus / Rutheni), Roxolanian (Roxolanus / Roxolani) or of Ruthenian origin, Polish nation (gente Ruthenus, natione Polonus / gente Roxolani, natione vero Poloni), published in his In Warszaviensi Synodo provinciae Poloniae Pro dignitate sacerdotali oratio (Kraków, 1561) and Fidei catholicae confessio (Cologne, 1563), most likely to emphasize his origin and his attachment to the Republic. The role of women in Polish-Lithuanian society during the Renaissance is reflected in distinct women's literature, which has its beginning in anonymous "Senatulus, or the council of women" (Senatulus to jest sjem niewieści) from 1543 and especially Marcin Bielski's "Women's Parliament" (Syem Niewiesci), written in 1566-1567. The idea derives from the satirical Senatus sive Gynajkosynedrion by Erasmus of Rotterdam, published in 1528, which caused a wave of imitations in Europe. Bielski's work, however, brings a whole bunch of articles proposed by married women, widows and unmarried women to be passed at the Sejm, which have no equivalent in Erasmus's work. There is almost no satirical content, which is the core of Erasmus's work willing to point out the faults of women. The main element in Bielski's work is criticism of men (after "Aemulatores Erasmi? ..." by Justyna A. Kowalik, p. 259). The women point to the inefficiency of men's power over the country and their lack of concern for the common good of the Republic. Their arguments about the role of women in the world are based on the ancient tradition, when women not only advised men, but also ruled and fought for their own. This work provoked a whole series of brochures devoted to female matters, in which, however, the emphasis has been shifted more to discussion of women's clothing - "Reprimand of Women's Extravagant Attire" (Przygana wymyślnym strojom białogłowskim) from 1600 or "Maiden's Parliament" (Sejm panieński) by Jan Oleski (pseudonym), published before 1617. Authors like Klemens Janicki (1516-1543), Mikołaj Rej (1505-1569), Krzysztof Opaliński (1609-1655) and Wacław Potocki (1621-1696), condemned the variability of costumes as a national vice (after "Aemulatores Erasmi? ...", p. 253) and index of forbidden books of Bishop Marcin Szyszkowski of 1617 banned a large group of humorous, entertaining, often obscene texts, imbued with ambiguous eroticism, and for these reasons condemned by the counter-reformation and the new model of culture. Later, in 1625, in his "Votum on the improvement of the Commonwealth" (Votvm o naprawie Rzeczypospolitey) Szymon Starowolski railed against the Italian or Italianized women spoiling the youth, effeminacy of men and their reluctance to defend the eastern lands against invasions: "He, whom the caressed Italian courtesans have raised in pillows, being entangled with their gentle words and delicacies, he can't stand the hardships with us". The great diversity of costume dates at least to the time of Sigismund I. Janicki in his poem "On the Variety and Inconstancy of Polish Dress" (In poloni vestibus varietatem et inconstanciam) describes King Ladislaus Jagiello rising from the grave and unable to recognize Poles and Mikołaj Rej in his "Life of the Honest Man" (Żywot człowieka poczciwego), published in 1568, writes about "elaborate Italian and Spanish inventions, those strange coats [...] he will order the tailor to make him what they wear today. And I also hear in other countries, when you happen to paint [describe] every nation, then they paint a Pole naked and put the cloth in front of him with scissors, cut yourself as you deign". Venetian-born Polish writer Alessandro Guagnini dei Rizzoni (Aleksander Gwagnin), attributes this to the habit of Poles of visiting the most distant and diverse countries, from which foreign costumes and customs were brought to their homeland - "One can see in Poland, costumes of various nations, especially Italian, Spanish, and Hungarian, which is more common than others" (after "Obraz wieku panowania Zygmunta III ..." by Franciszek Siarczyński, p. 71). Works of art were commissioned from the best masters in Europe - silverware and jewelry in Nuremberg and Augsburg, paintings and fabrics in Venice and Flanders, armours in Nuremberg and Milan and other centers. For the tapestries representing the Deluge (about 5 pieces) commissioned in Flanders by Sigismund II Augustus in the early 1550s, considered one of the finest in Europe, the king paid the staggering sum of 60,000 (or 72,000) ducats. More than a century later, in 1665, their value was estimated at 1 million florins, while the Żywiec land at 600,000 thalers and the richly equipped Casimir Palace in Warsaw at 400,000 florins (after "Kolekcja tapiserii ..." by Ryszard Szmydki, p. 105). It was only a small part of the rich collection of fabrics of the Jagiellons, some of which were also acquired in Persia (like the carpets purchased in 1533 and 1553). Made of precious silk and woven with gold, they were much more valued than paintings. "The average price of a smaller rug on the 16th-century Venetian market was around 60 to 80 ducats, which was equal to the price for an altarpiece commissioned from a famous painter or even for an entire polyptych by a less-known master" (after "Jews and Muslims Made Visible ...", p. 213). In 1586, second-hand rug in Venice cost 85 ducats and 5 soldi and wall hangings bought from Flemish merchants 116 ducats, 5 lire and 8 soldi (after "Marriage in Italy, 1300-1650", p. 37). Around that time, in 1584, Tintoretto was only paid 20 ducats for a large painting of Adoration of the Cross (275 x 175 cm) with 6 figures for the church of San Marcuola and 49 ducats in 1588 for an altarpiece showing Saint Leonard with more then 5 figures for the Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice. In 1564 Titian informed King Philip II of Spain that he would have to pay 200 ducats for an autograph replica of the Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, but that he could have one by the workshop for just 50 ducats (after "Tintoretto ..." by Tom Nichols, p. 89, 243). The lesser value of the paintings meant that they were not so prominently displayed in inventories and correspondence. The royal collections in Spain were largely unaffected by major military conflicts, so many paintings as well as related letters were retained. Perhaps we will never know how many letters Titian sent to the monarchs of Poland-Lithuania, if any. When Poland regained independence in 1918 and quickly began to rebuild the devastated interiors of Wawel Royal Castle, there was no effigy of any monarch inside (possibly except for a portrait of a ruling Emperor of Austria, as the building served the military). In 1919, the systematic collection of museum collections for Wawel began (after "Rekonstrukcja i kreacja w odnowie Zamku na Wawelu" by Piotr M. Stępień, p. 39). The practice of creating portraits for clients from the territories of present-day Poland from study drawings can be attested from at least the early 16th century. The oldest known is the so-called "Book of effigies" (Visierungsbuch), which was lost during World War II. This was a collection of preparatory drawings depicting the Pomeranian dukes, who were related to the Jagiellons, mainly by Cranach's workshop. Among the oldest were portraits of Bogislaw X (1454-1523), Duke of Pomerania and his daughter-in-law Amalia of the Palatinate (1490-1524) by circle of Albrecht Dürer, created after 1513. All were probably made by members of the workshop sent to Pomerania or less likely by local artists and returned to patrons with ready effigies. On the occasion of the division of Pomerania in 1541 with his uncle Duke Barnim XI (IX), Duke Philip I commissioned a portrait from Lucas Cranach the Younger. This portrait, dated in upper left corner, is now in the National Museum in Szczecin, while the preparatory drawing, previously attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger or Albrecht Dürer, is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims. A monogramist I.S. from Cranach's workshop used the same set of study drawings to create another similar portrait of the duke, now in the Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg. Studies for the portraits of Princess Margaret of Pomerania (1518-1569) and Anne of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1502-1568), wife of Barnim XI (IX), both dating from around 1545, were meticulously described by a member of the workshop sent to Pomerania to create them indicating colors, fabrics, shapes to facilitate work in the artist's studio. Undoubtedly, based on similar drawings, Cranach's workshop created miniatures of the Jagiellons in the Czartoryski Museum. In the 1620s a court painter of Sigismund III Vasa created drawings or miniatures after which Peter Paul Rubens painted the portrait of the king (Heinz Kisters collection in Kreuzlingen), most likely as one of a series. The same court painter painted the full-length portrait of Sigismund at Wilanów Palace. Between 1644-1650 Jonas Suyderhoef, a Dutch engraver, active in Haarlem, created a print with effigy of Ladislaus IV Vasa after a painting by Pieter Claesz. Soutman (P. Soutman Pinxit Effigiavit et excud / I. Suÿderhoef Sculpsit) and around that time Soutman, also active in Haarlem, created a similar drawing with king's effigy (Albertina in Vienna). After the destructive Deluge (1655-1660), the country slowly recovered and the most important foreign orders were mainly silverware, including a large silver Polish eagle, the heraldic base for the royal crown, created by Abraham I Drentwett and Heinrich Mannlich in Augsburg, most likely for the coronation of Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki in 1669, now in the Moscow Kremlin. Foreign commissions for portraits revived more significantly during the reign of John III Sobieski. French painters such as Pierre Mignard, Henri Gascar and Alexandre-François Desportes (a brief stay in Poland, between 1695 and 1696), active mainly in Paris, are frequently credited as authors of portraits of members of the Sobieski family. Dutch painter Adriaen van der Werff, must have painted the 1696 portrait of Hedwig Elisabeth of Neuburg, wife of James Louis Sobieski, in Rotterdam or Düsseldorf, where he was active. The same Jan Frans van Douven, active in Düsseldorf from 1682, who made several effigies of James Louis and his wife. In the Library of the University of Warsaw preserved a preparatory drawing by Prosper Henricus Lankrink or a member of his workshop from about 1676 for a series of portraits of John III (Coninck in Polen conterfeyt wie hy in woonon ...), described in Dutch with the colors and names of the fabrics (violet, wit satin). Lankrink and his studio probably created them all in Antwerp as his stay in Poland is unconfirmed. A few years later, around 1693, Henri Gascar, who after 1680 moved from Paris to Rome, painted a realistic apotheosis of John III Sobieski surrounded by his family, depicting the king, his wife, their daughter and their three sons. A French engraver Benoît Farjat, active in Rome, made a print from this original painting which has probably not survived, dated '1693' (Romae Superiorum licentia anno 1693) lower left and signed in Latin upper right: "H. Gascar painted, Benoît Farjat engraved" (H. GASCAR PINX. / BENEDICTVS FARIAT SCVLP.). Two workshop copies of this painting are known - one in Wawel Castle in Kraków, and the other, most likely from a dowry of Teresa Kunegunda Sobieska, is in the Munich Residence. Such a realistic depiction of the family must have been based on study drawings created in Poland, as Gascar's stay in Poland is not confirmed in the sources. The French painter Nicolas de Largillière, probably worked in Paris on the portrait of Franciszek Zygmunt Gałecki (1645-1711), today in the State Museum in Schwerin. Also one of the most famous portraits in Polish collections - Equestrian portrait of Count Stanisław Kostka Potocki by Jacques Louis David from 1781 was created "remotely". A collection catalogue of the Wilanów Palace, published in 1834 mentioned that the portrait was completed in Paris "after a sketch made from life in the Naples Riding School". One of such modello or ricordo drawings is in the National Library of Poland (R.532/III). It was the same for the statues and reliefs with portraits. Some of the most beautiful examples preserved in Poland were ordered from the best foreign workshops. Among the oldest and best are the bronze epitaphs made in Nuremberg by the workshop of Hermann Vischer the Younger, Peter Vischer the Elder and Hans Vischer in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, such as the epitaph of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus in Kraków, epitaph of Andrzej Szamotulski (d. 1511), voivode of Poznań, in Szamotuły, tomb of Piotr Kmita of Wiśnicz and of Cardinal Frederick Jagiellon (d. 1503), both at the Wawel Cathedral and tomb of King Sigismund I's banker, Seweryn Boner and his wife Zofia Bonerowa née Bethman at St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków. Around 1687, "Victorious King" John III Sobieski ordered large quantities of sculptures in Antwerp from the workshop of Artus Quellinus II, his son Thomas II and Lodewijk Willemsens and in Amsterdam from the workshop of Bartholomeus Eggers for the decoration of the Wilanów Palace in Warsaw, including busts of the royal couple, today in Saint Petersburg. All of these statues and reliefs were based on drawings or portraits, possibly similar to the triple portrait of Cardinal Richelieu, made as a study for a bust to be made by the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome. For the equestrian statue of Prince Józef Poniatowski (1763-1813), made between 1826 and 1832 and inspired by the statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, the Danish-Icelandic sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), although he arrived from Rome to Warsaw in 1820, had to use other effigies of the prince. The initiator of the construction of the monument was Anna Potocka née Tyszkiewicz (1779-1867). The monument was confiscated by the Russian authorities after the November Uprising (1830-1831) and was returned to Warsaw in March 1922. After the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising, the Nazi German invaders ordered the statue to be blown up on December 16, 1944. A new cast of the sculpture, made in the years 1948-1951, was donated to Warsaw by the Kingdom of Denmark. Some sources also confirm this practice. During his second stay in Rome, Stanisław Reszka (1544-1600), who admired the paintings by Federico Barocci in Senigallia or the work of Giulio Romano in Mantua, again buys paintings, silver and gold plates. He sends many works of this kind as gifts to Poland. To Bernard Gołyński (1546-1599) he sends paintings, including a portrait of the king and his own effigy and for King Stephen Bathory a portrait of his nephew. These portraits of the monarch and his nephew were therefore made in Rome or Venice from study drawings or miniatures that Reszka brought. On another occasion, he sends eight porcelain "vessels" in a decorative casket to the king, purchased in Rome and to Wojciech Baranowski (1548-1615), Bishop of Przemyśl, a relief of St. Albert, carved in ebony. Through Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini (later Pope Clement VIII), papal nuncio in Poland between 1588-1589, he sends paintings purchased for the king, one of the Savior, embroidered "of the most excellent work" and St. Augustine, made of bird feathers, "the most beautiful" (pulcherrimum), as he says. To the royal secretary Rogulski, who came to Rome, he gives a silver inkwell, and the chamberlain of the chancellor Jan Zamoyski entrusts him with a precious stone to be repaired in Italy, but before that, Reszka consulted the Kraków goldsmiths. All of these objects, including the paintings, must have been the work of the best Italian artists, but names rarely appear in the sources. In 1584, King Stephen's nephew, Andrew Bathory, with his companions, purchased and commissioned many exquisite items from Venice, including gold cloth with coats of arms, gold-embossed Cordovan (cuir de Cordoue) leather wallpapers, made by the goldsmith Bartolomeo del Calice. Another time he bought "12 bowls, 16 silver orbs" (12 scudellas, orbes 16 argenteos) from Mazziola and supervised the artist working on the execution of "glass vessels" (vasorum vitreorum). In Rome, they visit a certain Giacomo the Spaniard to see the "marvels of art" (mirabilia artis), where Bathory probably bought the trinkets and fine paintings, later shown to the delegates of the Jędrzejów Abbey. Visitors from Poland-Lithuania gave and received many valuable gifts. In 1587, the Venetian Senate, through two important citizens, offered Cardinal Andrew Bathory, who came as an envoy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with the announcement of the election of Sigismund III, two silver basins and jugs, four trays and six candelabra "of beautiful work" (pulchri operis). The Pope gives two medals with his image to Rogulski, and a gold chain to Cardinal Aldobrandini. After returning to Poland, Cardinal Bathory gives Queen Anna Jagiellon a coral cross, received from Cardinal Borromeo, and a box of nacre (ex madre perla), receiving a beautiful, expensive ring in return. Many artists were also engaged in Italy for the Commonwealth. King Stephen entrusts his nephew with the mission of bringing to the royal court architects who master the art of building fortresses and castles. Urged by the king, Reszka makes efforts through Count Taso, however, only a few months after his arrival he manages to get into the royal service Leopard Rapini, a Roman architect for an annual salary of 600 florins. On his way back to Poland, Simone Genga, architect and military engineer from Urbino, was admitted as a courtier in the presence of the Archbishop of Senigallia. We learn from Giorgio Vasari that Wawrzyniec Spytek Jordan (1518-1568), an art lover who frequented the thermal baths near Verona, was offered a small painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross, painted by Giovanni Francesco Caroto. Stanisław Tomkowicz (1850-1933) speculated that the Lamentation of Christ, inspired by Michelangelo's "Florentine Pieta" in the Biecz Collegiate Church, could be this painting. However, it is very likely that it was brought to Poland by a member of the Sułkowski family and its attribution to Caroto is rejected. Wawrzyniec, "a man of great authority with the King of Poland", according to Vasari, also brought to Poland-Lithuania the Italian sculptor Bartolomeo Ridolfi and his son Ottaviano, where they created numerous works in stucco, large figures and medallions and prepared designs for palaces and other buildings. Ridolfi was employed by King Sigismund Augustus "with honorable salaries" (Spitech Giordan grandissimo Signore in Polonia appresso al Re, condotto con onorati stipendi al detto Re di Polonia), but all his works were most likely destroyed during the Deluge. Bartolomeo Orfalla, a townsman from Verona, carried out exploratory drilling in the Spytek's estates to find salt similar to that mined in Bochnia and Wieliczka and Wawrzyniec's magnificent tombstone in the Church of St. Catherine and St. Margaret in Kraków was sculpted by Santi Gucci in 1603. The Italians also had many effigies of Polish-Lithuanian monarchs, many of which were forgotten when the Commonwealth ceased to be a leading European power after the Deluge (1655-1660). According to Maciej Rywocki's peregrination books from 1584-1587, written by the mentor and steward of the Kryski brothers from Masovia, during their three-year journey to Italy for study and education, in the Villa Medici in Rome, owned by Cardinal Ferdinando, later Grand Duke of Tuscany, in the gallery of portrait paintings, he saw "with all Polish kings and King Stephen and the queen [Anna Jagiellon] very resembling". This effigy of the elected queen of the Commonwealth, possibly by a Venetian painter, undoubtedly resembled the portraits of her dear friend Bianca Cappello, a noble Venetian lady and Grand Duchess of Tuscany. According to Stanisław Reszka, who was Ferdinando's guest in Florence in 1588, the Grand Duke owned a ritrat (portrait, from the Italian ritratto) of King Sigismund III Vasa and his father John III of Sweden. Reszka sent him a map of the Commonwealth made on satin on which there was also a portrait of Sigismund III (Posłałem też księciu Jegomości aquilam na hatłasie pięknie drukowaną Regnorum Polonorum, który był barzo wdzięczen. Tam też jest wyrażona twarz Króla Jmci, acz też ma ritrat i Króla Jmci szwedzkiego, a także i Pana naszego) (after "Włoskie przygody Polaków ..." by Alojzy Sajkowski, p. 104). A few decades earlier, Jan Ocieski (1501-1563), secretary of King Sigismund I, wrote in his travel diary to Rome (1540-1541) the information about a portrait of King Sigismund, which was in the possession of the cardinal S. Quatuor with an extremely flattering note: "this is a king like never before" (hic est rex, cui similis non est inventus), and "who is the wisest king, and the most experienced in dealing with things" (qui est prudentissimus rex et usu tractandarum rerum probatissimus), according to this cardinal (after "Polskie dzienniki podróży ..." by Kazimierz Hartleb, pp. 52, 55-57, 67-68). The situation was similar in other European countries. After the death of Ladislaus IV Vasa in 1648, Francesco Magni (1598-1652), lord of Strážnice in Moravia, ordered the portrait of the Polish-Lithuanian monarch to be moved from the representative piano nobile, a gallery with portraits of the Habsburgs, his ancestors, relatives, and benefactors, to his private room on the second floor of the castle (after "Portrait of Władysław IV from the Oval Gallery ..." by Monika Kuhnke, Jacek Żukowski, p. 75). The original portraits of King Ladislaus IV and Queen Marie Casimire, after which copies were made in the 18th century for the Ancestral Gallery (Ahnengalerie) of the Munich Residence, were considered to represent Charles X Gustavus of Sweden (CAROLUS X GUSTAVUS) and his granddaughter Ulrika Eleonora (1688-1741), Queen of Sweden (UDALRICA ELEONORA). The massive destruction of the Commonwealth's heritage and post-war chaos also contributed to such mistakes in Poland. Thus, in the gallery of 22 portraits of the kings of Poland, painted between 1768 and 1771 by Marcello Bacciarelli to embellish the so-called Marble Room of the Royal Castle in Warsaw, King Sigismund II Augustus is Jogaila (VLADISLAUS JAGIELLO, inventory number ZKW/2713/ab) and son of Anna Jagellonica (1503-1547), Archduke Charles II of Austria (1540-1590) was presented as Sigismund II Augustus (SIGISMUNDUS AUGUSTUS, ZKW/2719/ab), according to the descriptions under the images. These portraits are copies of paintings by Peter Danckerts de Rij dating from around 1643 (Nieborów Palace, NB 472 MNW, NB 473 MNW, deposited at the Royal Castle in Warsaw), based on lost originals. During the Deluge (1655-1660), when the situation was desperate and many people expected the barbarian invaders to totally destroy the Realm of Venus - they plundered and burned the majority of the Commonwealth's cities and fortresses and planned the first partition of the country (Treaty of Radnot), King John Casimir Vasa, a descendant of the Jagiellons, turned to a woman - the Virgin Mary for protection. At the initiative of his wife Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga in the fortified city of Lviv in Ruthenia on April 1, 1656, he proclaimed the Virgin his Patroness and Queen of his countries (Ciebie za Patronkę moją i za Królowę państw moich dzisiaj obieram). Soon, when the invaders were repelled, the medieval Byzantine icon of the Black Madonna (Hodegetria) of Częstochowa with scars on her face, revered by both Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians, and already surrounded by a cult, became the holiest of all Poland. The fortified sanctuary of the Black Madonna at Bright Mountain (Jasna Góra) was defended from pillage and destruction by the armies of the "Brigand of Europe" in late 1655, a Ruthenian-style riza (robe) was made for the Virgin and adorned with the most beautiful examples of Baroque and Renaissance jewelry offered by pilgrims, a perfect illustration of the country's culture and its diversity. The main statue of the beautiful residence of the "Victorious King" John III Sobieski, who saved Vienna from plunder and destruction in 1683 - Wilanów Palace, except for the planned equestrian monument of the king, was not the statue of Mars, god of war, nor of Apollo, god of the arts, nor even of Jupiter, king of the gods, but of Minerva - Pallas, goddess of wisdom. It was most likely created by the workshop of Artus Quellinus II in Antwerp or by Bartholomeus Eggers in Amsterdam and placed in the upper pavilion crowning the entire structure. Unfortunately, this large marble statue, as well as many others, including busts of the king and queen, were looted by the Russian army in 1707. In "The Register of Carrara marble statues and other objects taken from Willanów in August 1707" (Connotacya Statui Marmuru Karrarskiego y innych rzeczy w Willanowie pobranych An. August 1707), it was described as a "Satue of Pallas [...] in the window of the room above the entrance to the palace, resting her right hand on a gilded marble shield with the inscription Vigilando Quiesco [In watching I rest]" (Statua Pallas [...] w oknie salnym nad weysciem do Pałacu podpierayacey ręką prawą o tarczę z Marmuru wyrobioną pozłocistą, na ktorey Napis Vigilando Quiesco). Later, it most likely decorated the Kamenny Theater in Saint Petersburg (demolished after 1886), which Johann Gottlieb Georgi described in his "Description of the Russian Imperial Capital ...", published in 1794: "Above the main entrance is the image of a seated Minerva made of Carrara marble, with her symbols, and on the shield: Vigilando quiesco". The fact that nothing (or almost) preserved does not mean that nothing existed, so perhaps even the stay of some or several great European artists in Poland-Lithuania is still to be discovered.

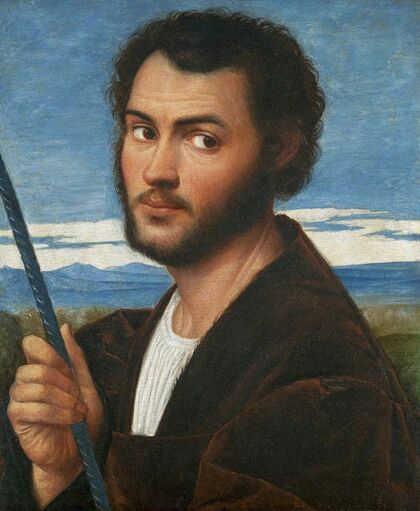

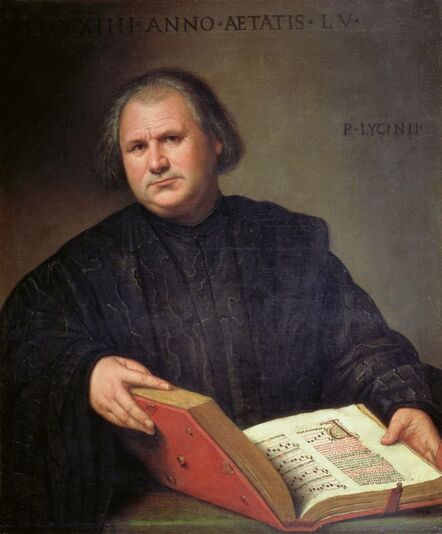

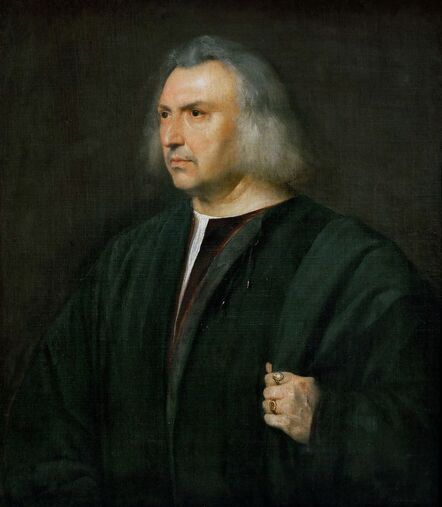

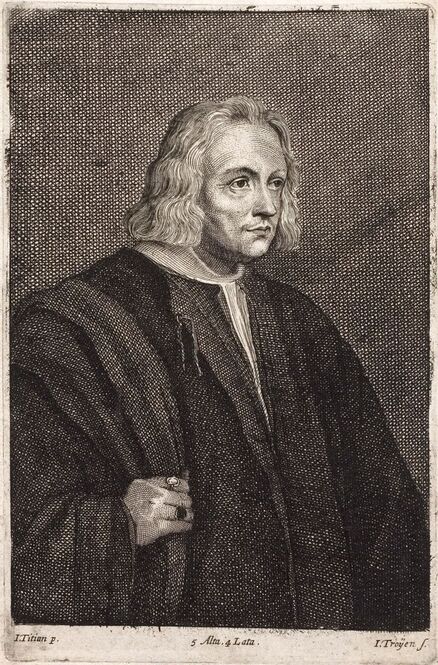

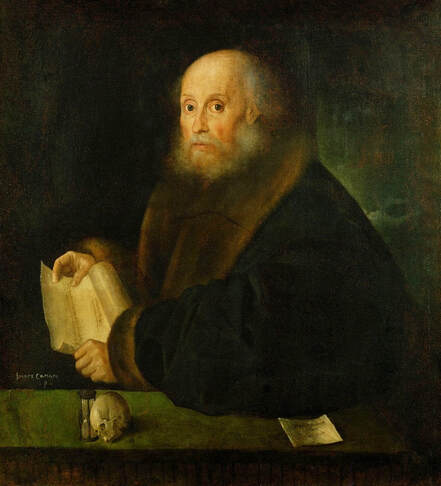

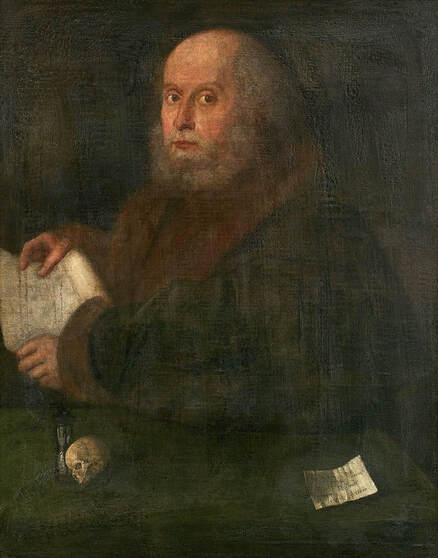

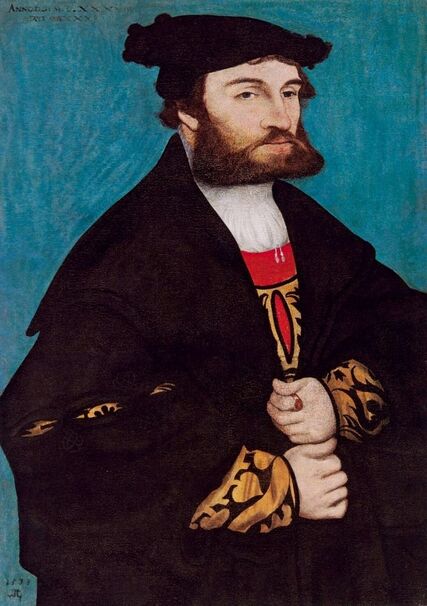

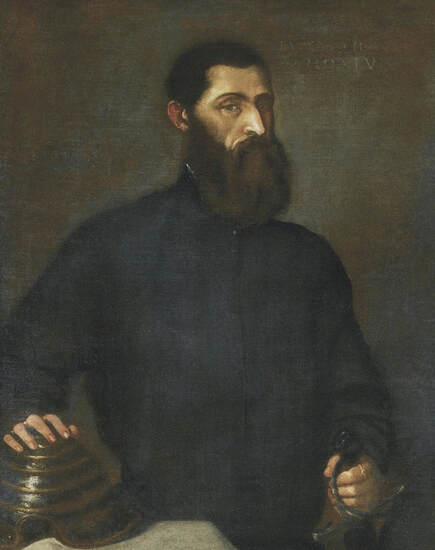

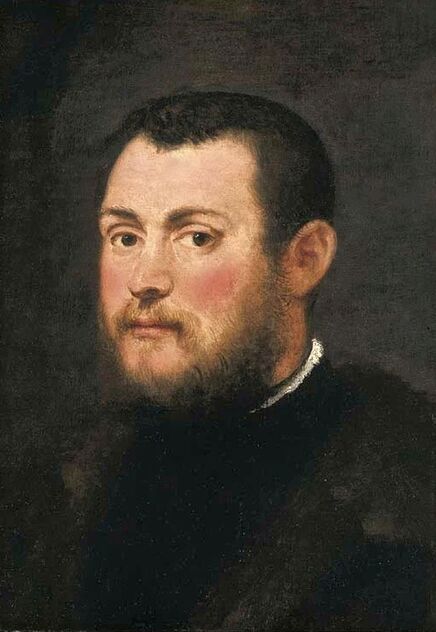

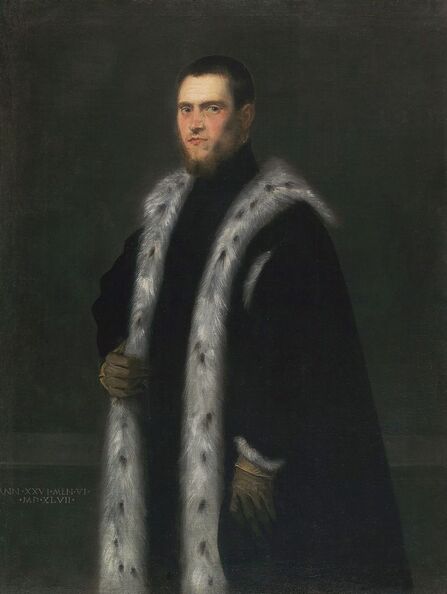

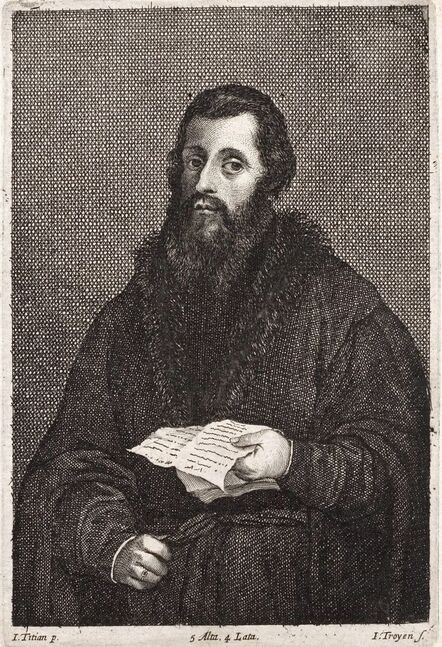

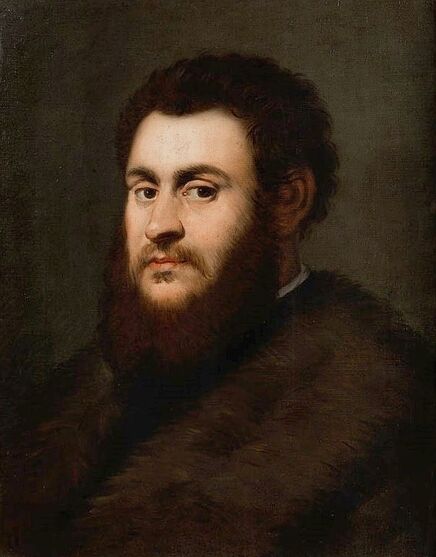

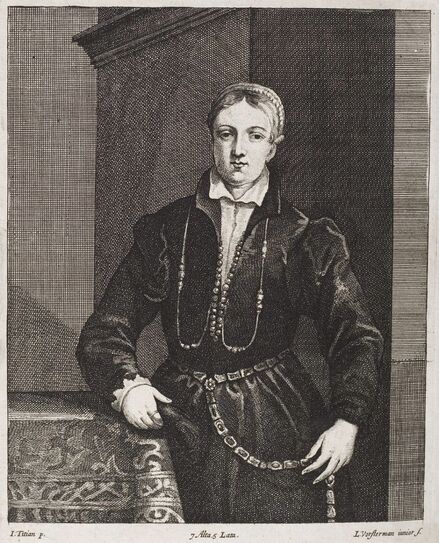

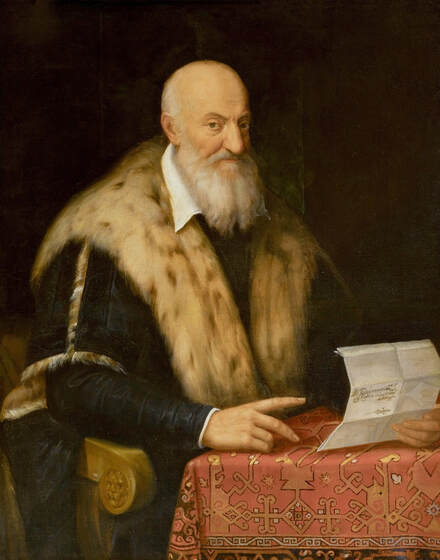

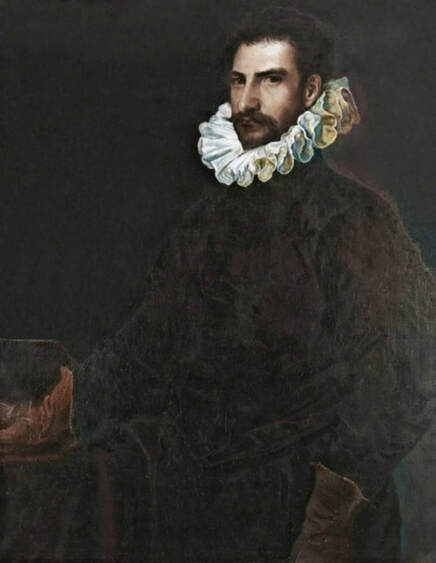

Portrait of Royal jeweller Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio aged 47 receiving a medallion from the Polish Royal Eagle with monogram of King Sigismund Augustus (SA) on his chest by Paris Bordone, 1547-1553, Wawel Royal Castle.

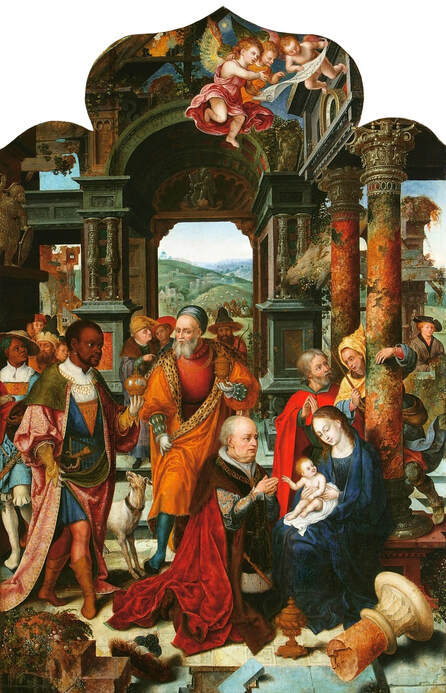

Adoration of the Magi with portraits of Elizabeth of Austria, Casimir IV Jagiellon and Jogaila of Lithuania by Stanisław Durink

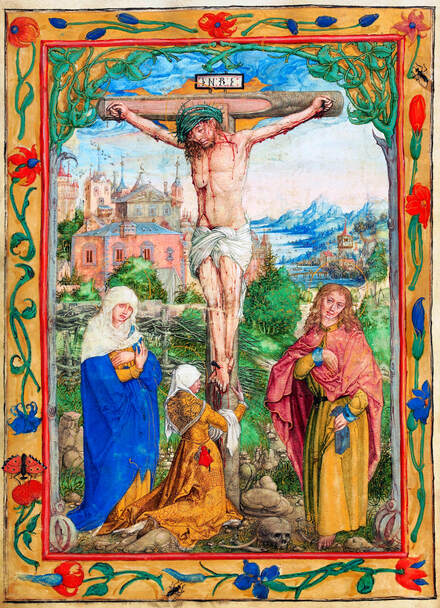

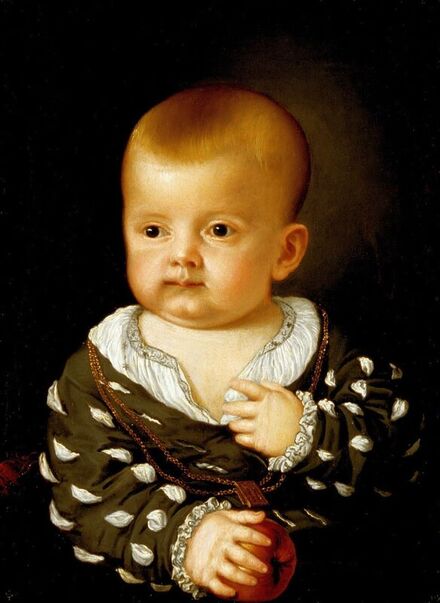

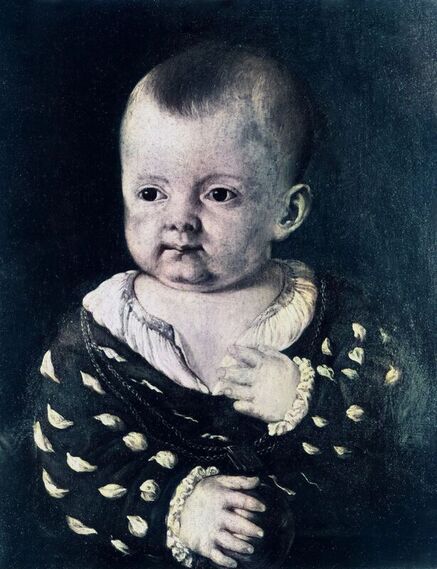

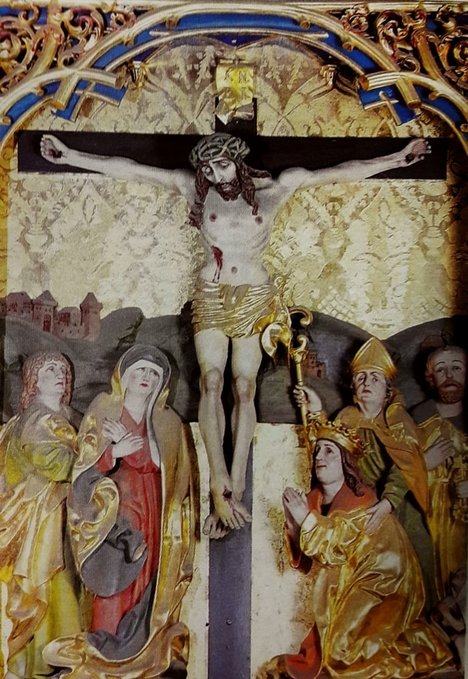

The portrait of King Ladislaus II Jagiello (Jogaila of Lithuania) as one of the Biblical Magi, venerated as saints in the Catholic Church, in the scene of the Adoration of the Magi is one of the oldest effigies of the first monarch of the united Poland-Lithuania. The painting is a section of the Our Lady of Sorrows Triptych in the Holy Cross Chapel (also known as the Jagiellon Chapel) at the Wawel Cathedral, which was built between 1467-1477 as a burial chapel for King Casimir IV Jagiellon (1427-1492) and his wife Elizabeth of Austria (1436-1505) - lower section, reverse of the right wing.

The triptych is considered the foundation of Queen Elizabeth mourning the death of her son Casimir Jagiellon (1458-1484), future Saint - her coat of arms, of the Habsburg family, as well as the Polish eagle and Lithuanian knight are in the lower part of the frame. The text of the Stabat Mater anthem on the frame could also indicate this (after "Malarstwo polskie: Gotyk, renesans, wczesny manieryzm" by Michał Walicki, p. 313). It is because of the great and unmistakable resemblance to the king's effigy on his tombstone in the same cathedral, the context and European tradition that one of the Magi is identified as a portrait of Jogaila. He was also depicted as one of the scholars in the scene of the Christ among the doctors in the same triptych. Consequently, the other two Magi are identified as effigies of other Polish rulers - Casimir the Great and Louis of Hungary. The other men in the background could be courtiers, including the painter's self-portrait (the man in the center, looking at the viewer), according to the well-known European tradition. Paintings in this triptych are attributed to Stanisław Durink (Durynk, Doring, Durniik, Durnijk, During, Dozinlk, Durimk), "painter and illuminator of king Casimir of Poland" (pictor et, illuminaitor Casimiri regnis Poloniae), as he is called in the documents of 1451, 1462 and 1463, born in Kraków (Stanislai Durimk de Cracovia). Durink was a son of Petrus Gleywiczer alias Olsleger, an oil merchant from Gliwice in Silesia. He died childless before 26 January 1492. If the majority of these effigies are disguised portraits of real people, why not the Madonna? This effigy seems too general, however, there are two important features that are not visible at first glance - the protruding lower lip of the Habsburgs and Dukes of Masovia and the depiction of the eyes, similar to the portrait of Queen Elizabeth, presumed founder of the triptych, in Vienna (Kunsthistorisches Museum, GG 4648). Therefore Melchior, the oldest member of the Magi, traditionally called the King of Persia, who brought the gift of gold to Jesus, is not Casimir the Great, but Casimir IV Jagiellon, Elizabeth's husband and the son of Jogaila. His effigy can also be compared to the counterpart of the portrait of Elizabeth in Vienna (GG 4649), which, like the Queen's portrait, was based on the depiction of the couple from the Family Tree of Emperor Maximilian I by Konrad Doll, painted in 1497 (Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, reproduced in a lithograph by Joseph Lanzedelly from 1820). Casimir IV was depicted with a longer beard in a print in Theatrum virorum eruditione singulari clarorum by Paul Freher (Berlin State Library), published in 1688 in Nuremberg. The last monarch (Louis of Hungary on the right) was depicted from behind, so it is less likely to be a "disguised portrait". The purpose of these informal portraits was ideological - to legitimize the dynastic rule of the Jagiellons in the elective monarchy, a reminder that despite their rule is dependent on the will of the magnates, their power was bestowed on them by God. The Roman Catholic Chapel of the Holy Cross was decorated with Russo-Bizantine frescoes created by Pskov painters in 1470, so its ideological program was dressed for followers of the two main religions of Poland-Lithuania: Greek and Roman. Byzantine Patriarchal cross became the symbol of Jagiellonian dynasty (Cross of Jagiellons) and reliquary of the True Cross (Vera Crux) of Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1118-1180), given to Jogaila in 1420 by emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (1350-1425), was a coronation cross of the Polish monarchs (today in the Notre-Dame de Paris - Croix Palatine).

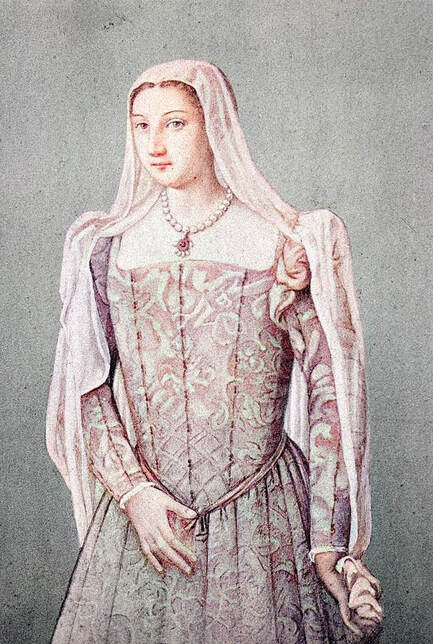

Adoration of the Magi with portraits of Elizabeth of Austria as Madonna and Casimir IV Jagiellon and Jogaila of Lithuania as the Magi by Stanisław Durink, ca. 1484, Wawel Cathedral.

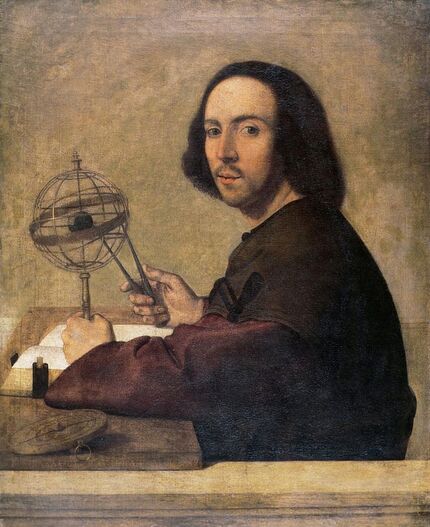

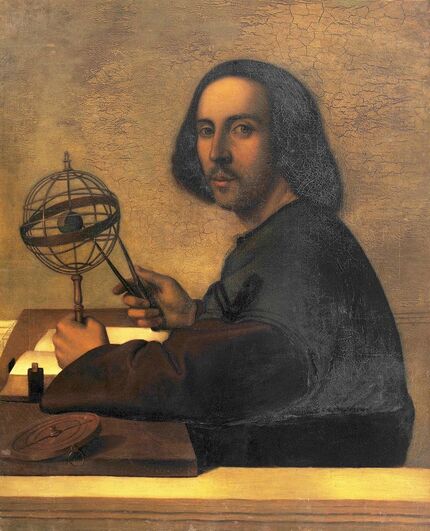

Family of Nicolaus Copernicus as donors by Michel Sittow

In 1484 Michel Sittow (ca. 1469-1525), a painter born in the Hanseatic city of Reval in Livonia (now Tallinn in Estonia) moved to Bruges in the Low Countries, at that time a leading economic center of Europe where painting workshops flourished. It is thought that he worked as an apprentice in the workshop of Hans Memling till 1488 and that he traveled to Italy. When in Bruges Sittow undoubtedly had the opportunity to meet Mikołaj Polak (Claeys Polains), a painter from Poland, who in 1485 was sued by the Bruges Guild of Saint Luke for using inferior Polish lazurite.

From 1492 Sittow worked in Toledo for Queen Isabella I of Castile as a court painter. He left Spain in 1502 and was presumably working in Flanders for Joanna of Castile and her husband Philip the Handsome. Michel probably visited London between 1503-1505, although this trip is not documented. Several portraits of English monarchs attributed to him could also have been made in Flanders on the basis of drawings sent from London. In 1506 the painter returned to Reval, where he joined the local guild of painters in 1507, and married in 1508. In 1514 he was called to Copenhagen to portray Christian II of Denmark. The portrait was intended to be a gift to Christian's fiancée, Isabella of Austria, a granddaughter of Isabella of Castile. From Denmark he traveled to Flanders, where he entered the service of Margaret of Austria, then regent of the Netherlands, and from there to Spain, where he returned to the service of Ferdinand II of Aragon, husband of Queen Isabella. When Ferdinand died in 1516, Sittow continued as court painter for his grandson Charles I, future Emperor Charles V. On an unknown date (between 1516 and 1518) Michel Sittow returned to Reval, where he married Dorothie, daughter of a merchant named Allunsze. In 1523, Sittow held the position of Aldermann (guild leader) and he died of plague in his hometown between December 20, 1525 and January 20, 1526. It is possible that between 1488-1492 Sittow returned to Tallinn. If he traveled by sea to or from Bruges or Spain, his possible stop was one of the largest seaports on the Baltic Sea - Gdańsk in Polish Prussia, the main port of Poland-Lithuania. If he traveled by land, he undoubtedly traveled through Polish Prussia and one of the biggest cities on the route from Bruges to Livonia - Toruń, where king Jagiello built a castle between 1424 and 1428 (Dybów Castle). One of the major works from this period in Toruń is a late Gothic painting depicting the Descent from the Cross with donors, today in the Diocesan Museum in Pelplin (tempera on oak panel, 214 x 146 cm, inventory number MDP/32/M, earlier 184984). It was earlier in the Toruń Cathedral and originally, probably, in the demolished church of St. Lawrence in Toruń or as the property of the Brotherhood of Corpus Christi at the Cathedral. The work was showcased during an international exhibition at the National Museum in Warsaw and the Royal Castle in Warsaw - "Europa Jagellonica 1386-1572" in 2012/2013, devoted to the period in which the "Jagiellonian dynasty was the dominant political and cultural force in this part of Europe". Many authors underline inspirations and influences of Netherlandish painting in this panel, especially by Rogier van der Weyden (after "Sztuka gotycka w Toruniu" by Juliusz Raczkowski, Krzysztof Budzowski, p. 58), the master of Memling, who had served his apprenticeship in his Brussels workshop. The landscape and technique can even bring to mind works by Giovanni Bellini (d. 1516), like Deposition (Gallerie dell'Accademia) and colors the works by Spanish masters of the late 15th century. It is known that in 1494 a Dutch painter named Johannes of Zeerug stayed at the court of king John I Albert. He could be the possible author of Sacra Conversazione with Saint Barbara and Saint Catherine and donors from Przyczyna Górna, created in 1496 (Archdiocesan Museum in Poznań). This painting was founded to the Parish church in Dębno near Nowe Miasto nad Wartą by Ambroży Pampowski of Poronia coat of arms (ca. 1444-1510), Starost General of Greater Poland, an important official close to the royal court, who was depicted as donor with his first wife Zofia Kot of Doliwa coat of arms (d. 1493). The style of the painting in Pelplin is different and resembles the works attributed to Michel Sittow - Portrait of a man with a pink - Callimachus (Getty Center), Portrait of King Christian II of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst), Madonna and Child (Gemäldegalerie in Berlin) and Portrait of Diego de Guevara (National Gallery of Art in Washington). He was also the only known artist of this level from this part of Europe, educated in the Netherlands, to whom the work can be attributed. The Descent from the Cross in Pelplin was a part of a triptych. However, the two other panels were created much later in different workshops. Basing on style and costumes these two other paintings are attributed to local workshop under Netherlandish and Westphalian influences and dated to around 1500. All three paintings were transferred to the Museum in Pelplin in 1928 and the central panel showing the Christ crowned with thorns was lost during World War II. The left wing representing Flagellation of Christ is now back in the Toruń Cathedral. This painting has almost identical dimensions as the Descent from the Cross (tempera on oak panel, 213 x 147 cm) and one of the soldiers tormenting Jesus has a royal monogram under crown embroidered with pearls on his chest. This intertwined monogram can be read as IARP (Ioannes Albertus Rex Poloniae), i.e. John I Albert, King of Poland from 1492 to his death in 1501. The founder of this painting depicted as kneeling donor in the right corner of the panel was therefore closely connected with the royal court. This man bears a striking resemblance to known likenesses of the most famous man from Toruń - Nicolaus Copernicus (born on 19 February 1473), who was baptized in the Toruń Cathedral. Some authors consider it to be an authentic image of the astronomer (after "Utworzenie Kociewskiego Centrum Kultury", 29.06.2022) founded by him in his lifetime. If the donor from the Flagellation painting is Copernicus, therefore the donors from the earlier Descent from the Cross should be his parents and siblings. Nicolaus' father, also Nicolaus was a wealthy merchant from Kraków, son of John. He was born around 1420. There is much debate as to whether he was German or Polish, perhaps he was just a typical representative of the Jagiellonian multiculturalism. He moved to Toruń before 1458 and before 1448 he traded in Slovak copper, which was transported by the Vistula to Gdańsk and then exported to other countries. In 1461, he granted a loan to the city of Toruń to fight against the Teutonic Order. Copernicus the Elder married Barbara Watzenrode, sister of Lucas Watzenrode (1447-1512), Prince-Bishop of Warmia, who studied in Kraków, Cologne and Bologna. The couple had four children, Andreas, Barbara, Catharina and Nicolaus. Copernicus the father died in 1483 and his wife, who died after 1495, founded him a portrait epitaph, known today only from a copy, on which we can see a man with a mustache, with folded hands in prayer, with similar features to his son. This copy was commissioned in about 1618 by astronomer Jan Brożek (Ioannes Broscius) for the Kraków Academy and it was repainted around 1873 (Jagiellonian University Museum, oil on canvas, 60 x 47 cm). The father of astronomer died at the age of about 63, while depicted man in much younger, therefore the original epithaph was probably based on some earlier effigy. The facial features of a man from the Descent from the Cross are very similar. Elongated face with wider cheekbones of the woman from the painting is similar to effigies of Barbara Watzenrode's brother Lucas and her famous son. As it was said Nicolaus the Elder died in 1483, while Sittow moved to the Netherlands in about 1484. Such a wealthy merchant or his widow could afford to order a painting from the artist, who at that time was possibly in Gdańsk or Toruń or even created in Bruges, when he settled there, and sent to Toruń. The appearance of younger of boys match the age of future astronomer, who was 10 when his father died. Barbara and Nicolaus had two daughters Barbara and Catharine, while on the painting there is only one. The elder Barbara, entered the convent in Chełmno, where she later became an abbess and died in 1517. It is generally believed that it was she who was mentioned in the list of nuns under the year 1450 there (after "Cystersi w społeczeństwie Europy Środkowej" by Andrzej Marek Wyrwa, Józef Dobosz, p. 114 and "Leksykon zakonnic polskich epoki przedrozbiorowej" by Małgorzata Borkowska, p. 287), therefore she "left" her family over 20 years before Nicolaus the astronomer was born. Apart from costly Polish azurite, painters in Bruges and other locations needed Copernicus' copper, which although is naturally green, "with the addition of ammonia (easily obtained from urine), it turns blue. The color became chemically stable if lime was added, and this chemistry process produced a cheap, bright blue that became an allpurpose paint for walls, wood, and books" (after "All Things Medieval" by Ruth A. Johnston, p. 551). In Gdańsk English and Dutch merchants purchased cenere azzurre, a blue pigment prepared from carbonate of copper (after "Original treatises dating from the XIIth to XVIIIth centuries on the arts of painting in oil ... ", p. cc - cci), similar to that visible in the Descent from the Cross in Pelplin.

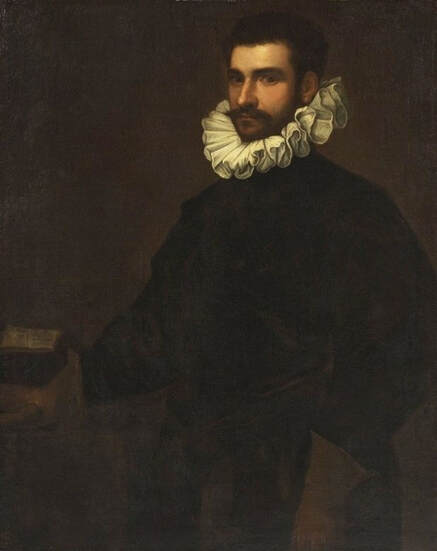

Portrait of merchant Nicolaus Copernicus the Elder (d. 1483) and his two sons as donors from the Descent from the Cross by Michel Sittow, ca. 1483-1492, Diocesan Museum in Pelplin.

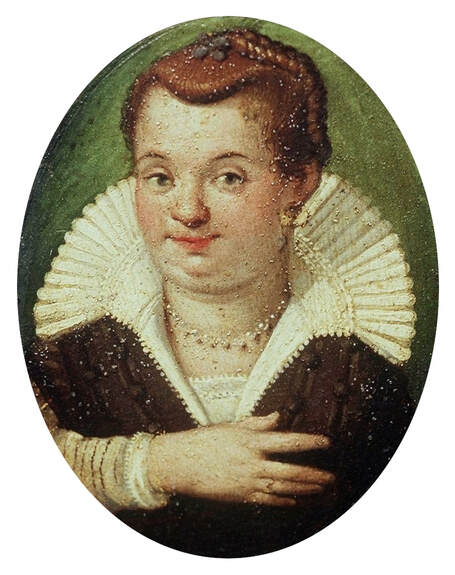

Portrait of Barbara Watzenrode and her daughter as donors from the Descent from the Cross by Michel Sittow, ca. 1483-1492, Diocesan Museum in Pelplin.

Descent from the Cross with family of Nicolaus Copernicus as donors by Michel Sittow, ca. 1483-1492, Diocesan Museum in Pelplin.

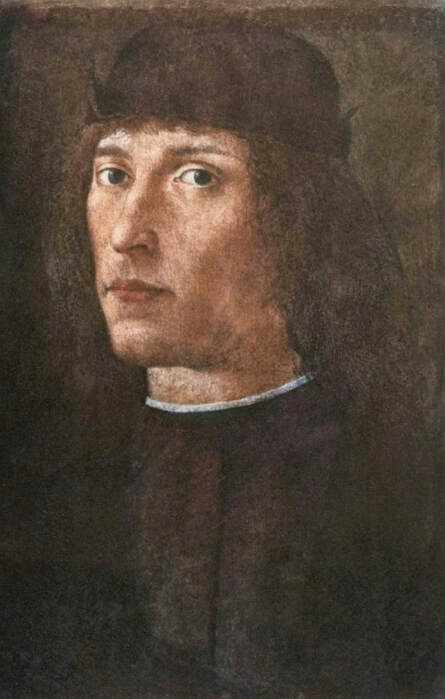

Portraits of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus by Michel Sittow and workshop of Giovanni Bellini

"A face brighter than Venus' and the hair of Phoebus Apollo ... [more striking] than the stone polished by Phidias or the paintings of Apelles", this is how Philippus Callimachus Experiens (1437-1496) describes in his poem the beauty of the young clergyman Lucio Fazini Maffei Fosforo (Lucidus Fosforus, d. 1503), who became bishop of Segni near Rome in 1481. He advises elsewhere an elderly man: "Although the reverence of a wrinkled brow with white hair is esteemed ... Quintilius should prefer to be effeminate, so that he might always be ready for the prostitutes and the boys" (after "A Sudden Terror: The Plot to Murder the Pope in Renaissance Rome" by Anthony F. D'Elia, p. 96, 98).

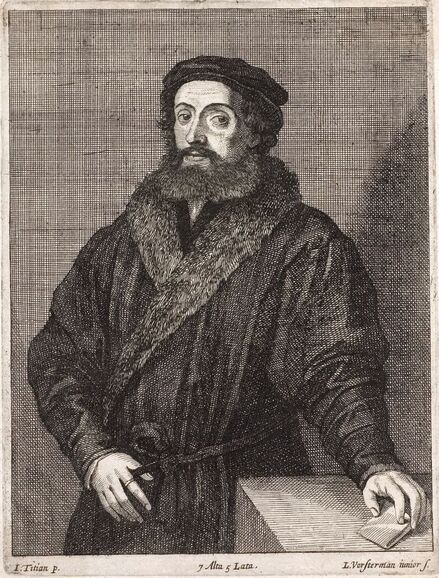

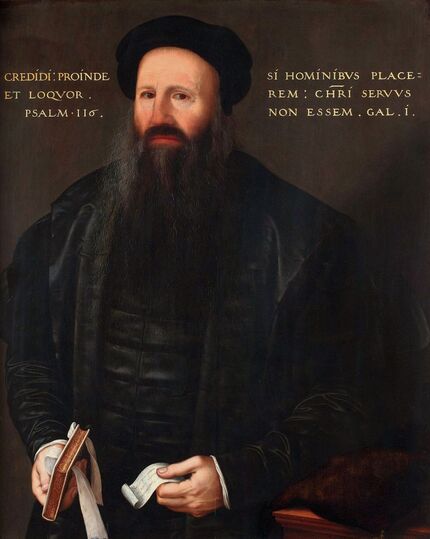

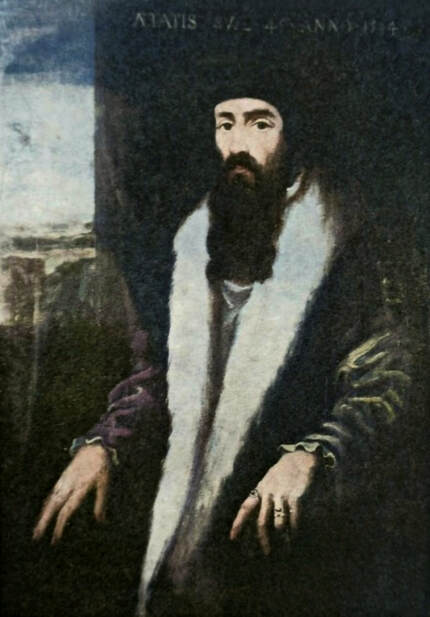

Callimachus, humanist, writer and diplomat, was born Filippo Buonaccorsi de Tebadis Experiens in San Gimignano in Tuscany, in Italy. He moved to Rome in 1462 and he become a member of the Roman Academy of Giulio Pomponio Leto (Julius Pomponius Laetus, 1428-1498), who was later charged with sodomy, conspiracy against Pope Paul II and heresy. Filippo was accused of participating in the assassination attempt on the pope in 1468 and fled through southern Italy (Apulia-Sicily) to Greece (Crete-Cyprus-Chios) and Turkey, and then to Poland (1469/1470). The homo-erotic verses were discovered among his papers, including one dedicated to Fazini. The punishment for love between two men in Poland-Lithuania was similar as probably in most of the countries of Medieval/Renaissance Europe, nevertheless in Poland-Lithuania, like Rheticus almost a century later, he easly found powerful protectors, who undobtedly perfectly knew about his "inclinations". First he found work with the Bishop of Lviv, Gregory of Sanok (d. 1477), a professor at the Kraków Academy. Later he became tutor to the sons of the King of Poland Casimir IV Jagiellon and carried out various diplomatic missions. In 1474 he was appointed royal secretary, in 1476 he became ambassador to Constantinople and in 1486 he was the king's representative in Venice. With the accession to the throne of his former pupil John Albert, his power and influence reached its maximum. In his writings, Buonaccorsi advocated the reinforcement of royal power. He also wrote poems and prose in Latin, although he is best known for his biographies of Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki, Bishop Gregory of Sanok, and King Ladislaus III Jagiellon. When in Poland, he also wrote love poems, many of which were addressed to his benefactress in Lviv with the name of Fannia Sventoka (Ad Fanniam Sventokam elegiacon carmen, In coronam sibi per Fanniam datam, In eum qui nive concreta collum Fanniae percusserat, De passere Fanniae, Narratio ad Fanniam de ejus errore, De gremio Fanniae, In picturam Fanniae, In reuma pro Fannia dolente oculos). This name is sometimes considered to be a pseudonym of Anna Ligęzina, daughter of Jan Feliks Tarnowski, or interpreted as Świętochna or Świętoszka (prude in Polish). The word Sventoka is also similar to Polish świntucha (rake, debauchee). Nevertheless, taking into consideration that some gay guys and transvestites like to use female nicknames, we cannot even be sure the "she" was indeed a woman. After the scandal in Rome, the poet had to be careful, fanatics could be anywhere. Almost two centries later, in 1647, transgender people were at the court of Crown Court Marshall Adam Kazanowski and Chancellor Jerzy Ossoliński. They were probably also at the royal court earlier. As a diplomat, Callimachus traveled a lot. His first stay in the royal city of Toruń is confirmed by his letter from this city to the Florentine merchant and banker Tommaso Portinari, dated June 4, 1474, regarding Hans Memling's altar "The Last Judgment", today in Gdańsk. In 1488 he settled for a few months, or maybe even longer, in the residence of bishop Piotr of Bnin, in Wolbórz near Piotrków and Łódź. That same year he went to Turkey and he took with him his young servant or secretary Nicholo (or Nicholaus), whom he calls "Nicholaus, my inmate", possibly Nicolaus Copernicus. Callimachus was on July 3, 1490 in Toruń and he lived there between 1494-1496, although in 1495 he left for Vilnius, Lublin, and finally to Kraków, where he died on September 1, 1496. Shortly before his death, on February 5, 1496, he purchased two houses in Toruń from Henryk Snellenberg, one was adjacent to the house of Lucas Watzenrode the Elder, maternal grandfather of Nicolaus Copernicus (after "Urania nr 1/2014", Janusz Małłek, p. 51-52). During his extended stay in Venice in 1477 and 1486, Callimachus established relations with the most eminent politicians, scholars and artists, like Gentile Bellini (d. 1507) and his younger brother Giovanni (d. 1516), a highly sought-after portraitist, who most probably created his portrait (after "Studia renesansowe", Volume 1, p. 135). In Getty Center in Los Angeles there is a "Portrait of a man with a pink", attributed to Michel Sittow (oil on panel, 23.5 cm x 17.4 cm, inventory number 69.PB.9). This painting was before 1938 in different collections in Paris, France and it was formerly attributed to Hans Memling. The man is holding a red carnation, a symbol of pure love (after "Signs & Symbols in Christian Art" by George Ferguson, p. 29). Clear inspiration of Venetian painting is visible in composition, especially by works of Giovanni Bellini (blue background, wooden parapet). The man's black costume, cap and hairstyle are also very Venetian, similar to that visible in Giovanni's self-portrait in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The self-portrait shows Giovanni as a young man, hence it should be dated to about 1460, as it is generally belived that he was born in about 1430. The costume and apperence of a man from the portrait in Los Angeles also resemble that in bronze epitaph of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus, created after 1496 by workshop of Hermann Vischer the Younger in Nuremberg to design by Veit Stoss (Basilica of Holy Trinity in Kraków). An exact copy of the Los Angeles portrait, attributed to Hans Memling or follower, is in the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków (oil on panel, 24.5 x 19 cm, inventory number V. 192). It was mentioned in a catalogue of the Museum from 1914 by Henryk Ochenkowski (Galerja obrazów: katalog tymczasowy) under the number 110 among other paintings by Italian school and a portrait of a man by school of Giovanni Bellini (oil on panel, 41 x 26.5 cm, item 4). The same catalogue catalogue also lists under number 158 a painting of Madonna and Child sitting before a curtain, which today is attributed to follower of Giovanni Bellini, and dated to about 1480 (Czartoryski Museum, inventory number MNK XII-202). The same man, although younger, was depicted in a painting attributed to Italian school, sold in Rudolstadt in Germany (oil on panel, 36 x 29 cm, Auktionshaus Wendl, October 29, 2022). His outfit, cap and hairstyle closely resemble those seen on the bronze medal with bust of Giovanni Bellini, created by Vittore Gambello and dated to about 1470/1480. The man stands in front of a curtain, which gives a view of a mountainous landscape. Inscription in English on verso on old adhesive label "The Portrait of Antonio Lanfranco ... at Palermo by J. Bellini", seems unreliable, because Jacopo Bellini, the father of Bellini brothers, died in about 1470 and no such inhabitant of Palermo who might have commissioned his portrait in Venice is mentioned in the sources. The style of this painting is close to workshop of Giovanni Bellini. It is highly possible that portrait of King John I Albert, Callimachus' pupil, commissioned by Toruń City Council to the Royal Chamber of the City Hall around 1645, which follows the same Venetian/Netherlandish pattern, was based on a lost original by Giovanni Bellini or Michel Sittow, created around 1492. If the author of inscription in English acquired the painting in Palermo, Sicily, then the mountin depicted in the background could be Mount Etna (Mongibello), an active volcano on the east coast of Sicily between the cities of Messina and Catania. In Quattrocento verse the hellishly boiling Mongibello was symbol of the vain torments of love and the insane fires of passion (after "Strong Words ..." by Lauro Martines, p. 135). The man's costume is also very similar to that seen in the portraits by Antonello da Messina (d. 1479), a painter from Messina, from the 1470s (Louvre Museum, MI 693 and Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, 18 (1964.7)). "I said: It's a joke, he pretends to love [...] I believe that you burn not only with the dim, weak, gentle flame of love. But as much violent fire Has ever accumulated on earth, So much of it burns in you with all its might, Or how many islands of the Tyrrhenian Sea and Sicily, famous for their volcanoes Exploding fire, brought here From the depths and locked in you" (Dicebam: Iocus est, amare fingit [...] Flammis et placido tepere amore / Credam, sed rapidi quod ignis usquam / In terris fuerat simul cohactum / In te viribus extuare cunctis / Aut incendivomo inclitas camino / Tyreni ac Siculi insulas profundi), writes Callimachus about his torments in his poem "To Gregory of Sanok" (Ad Gregorium Sanoceum, ad eundem) (after "Antologia poezji polsko-łacińskiej: 1470-1543", Antonina Jelicz, Kazimiera Jeżewska, p. 59).

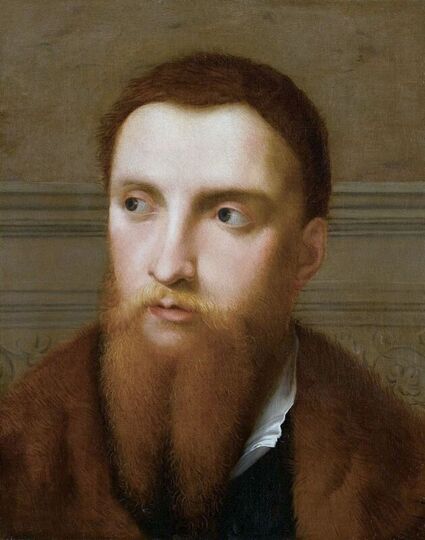

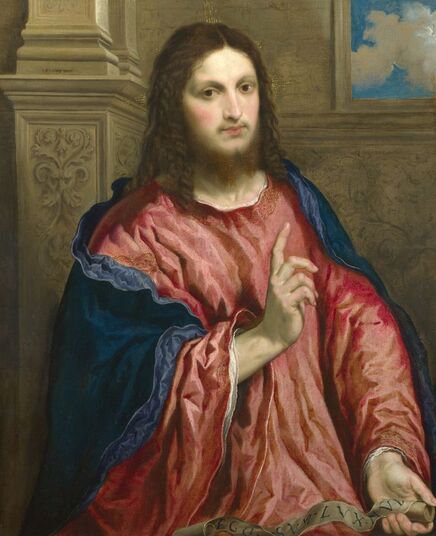

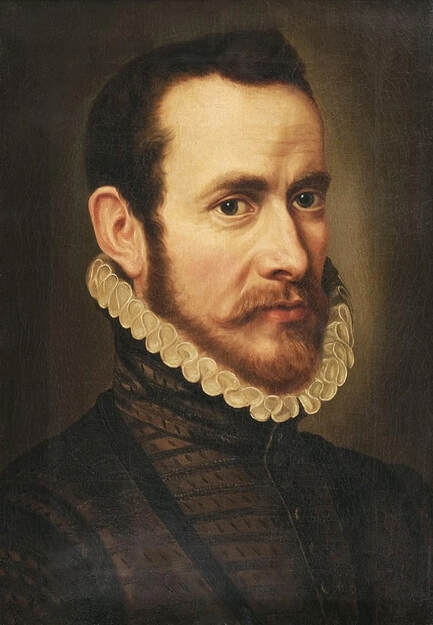

Portrait of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus (1437-1496) by workshop of Giovanni Bellini, ca. 1477 or after, Private collection.

Portrait of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus (1437-1496) holding a red carnation by Michel Sittow, ca. 1488-1492, Getty Center.

Portrait of Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus (1437-1496) holding a red carnation by workshop of Michel Sittow, ca. 1488-1492, Czartoryski Museum.

Portrait of John I Albert, King of Poland (1492-1501) in coronation robes by Toruń workshop, ca. 1645, Old Town City Hall in Toruń.

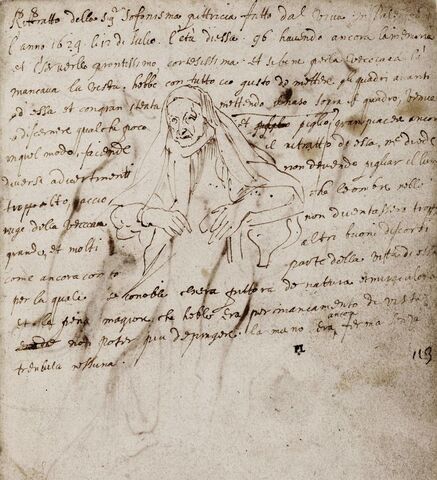

Portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus by circle of Giovanni Bellini

Szto piszesz do nas o tot wschod, kotoryi esmo tam tobe u Wilni s palacu naszoho do sadu urobiti roskazali, comments in Belarusian (Old Ruthenian) the Italian-born Queen Bona Sforza on the alterations in the renaissance palace loggia in Vilnius, capital of Lithuania, to be made by Italian architect and sculptor Bernardo Zanobi de Gianottis, called Romanus in a letter of August 25, 1539 from Kraków in Poland (after "Królowa Bona ..." by Władysław Pociecha, p. 185). It is a perfect example of Polish-Lithuanian diversity in the 15th and 16th centuries.