|

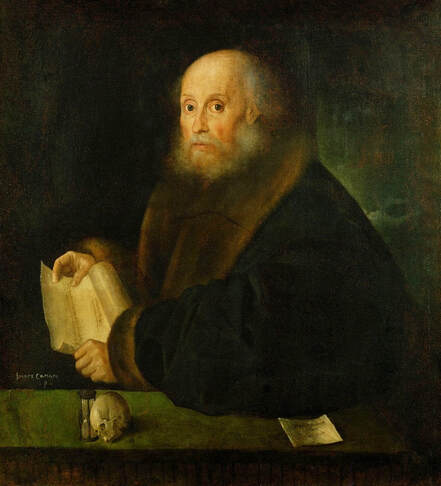

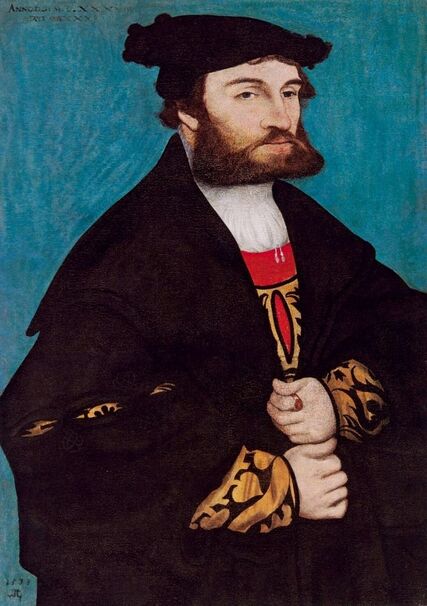

Portraits of Hedwig Jagiellon and Anna Jagellonica by Lucas Cranach the Elder

Despite numerous suitors for her hand, the Crown Princess Hedwig Jagiellon remained unmarried at the age of 17. In 1529, Krzysztof Szydłowiecki and Jan Tarnowski proposed to Damião de Góis, envoy of John III, king of Portugal, to marry Hedwig to king's brother Infante Louis of Portugal, Duke of Beja. At the same time negotiations were carried to marry her to Louis X, Duke of Bavaria and Habsburgs, on April 18, 1531 proposed Frederick, brother of Louis V, Count Palatine of the Rhine.

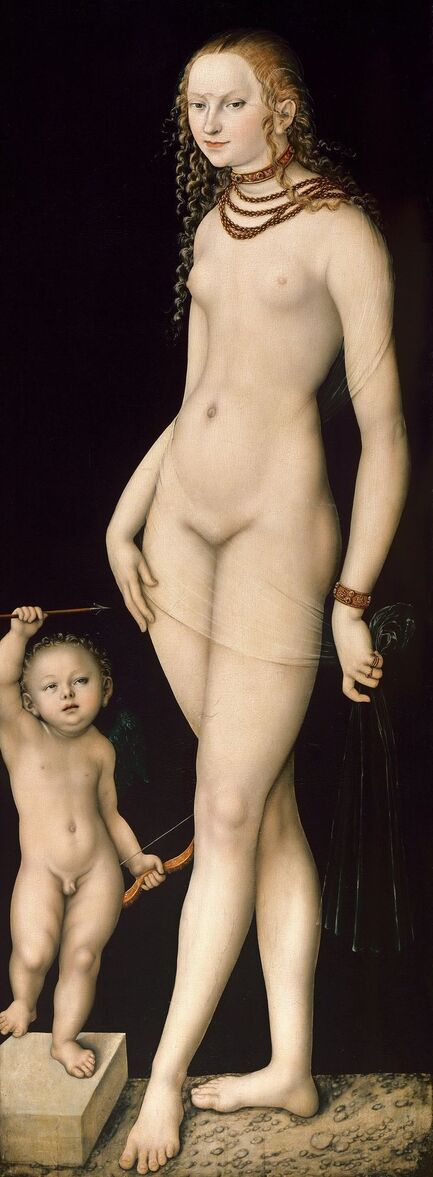

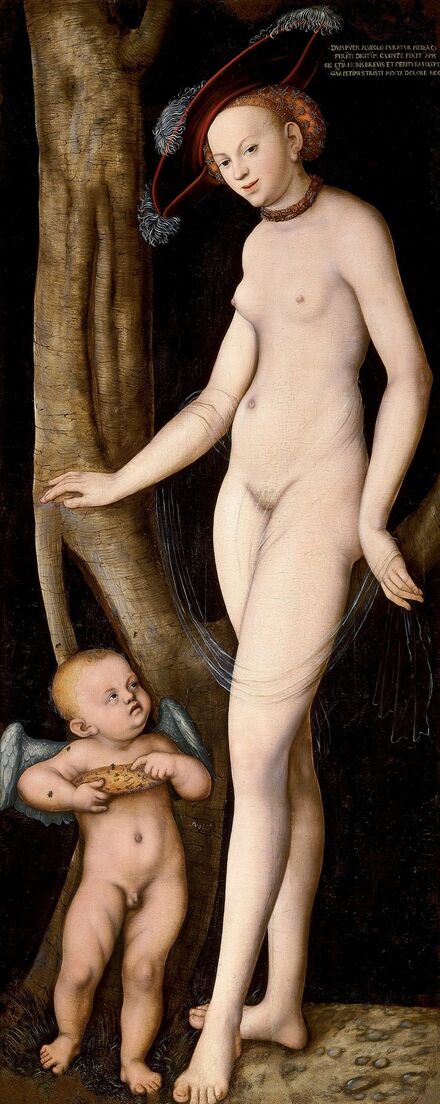

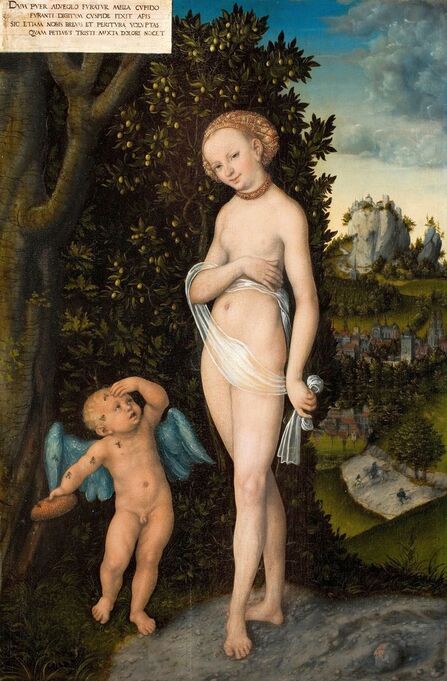

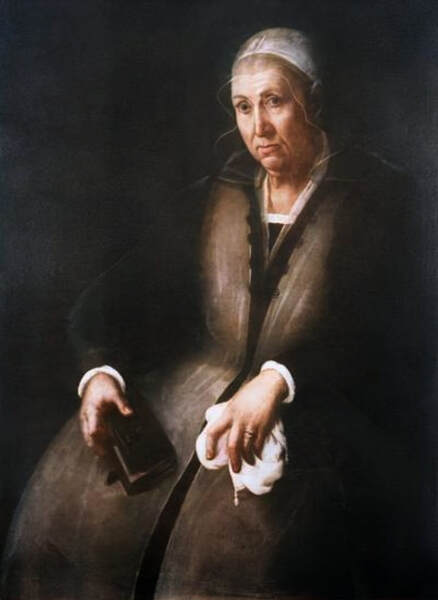

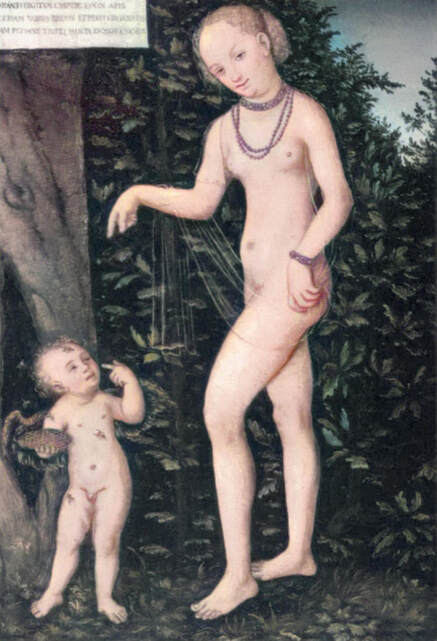

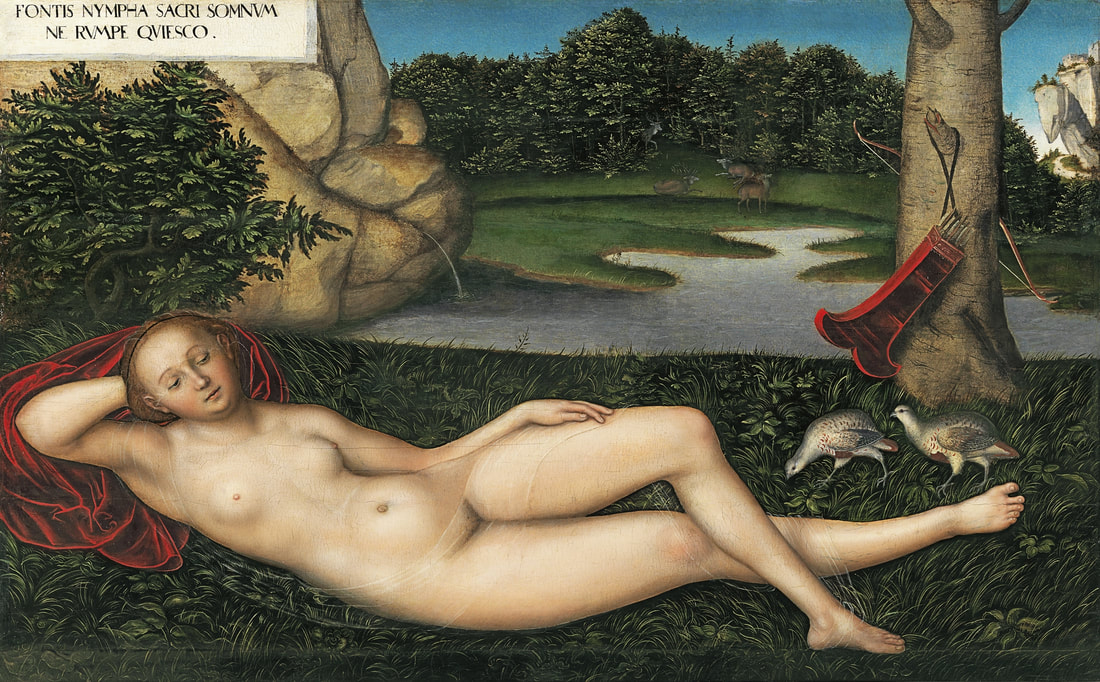

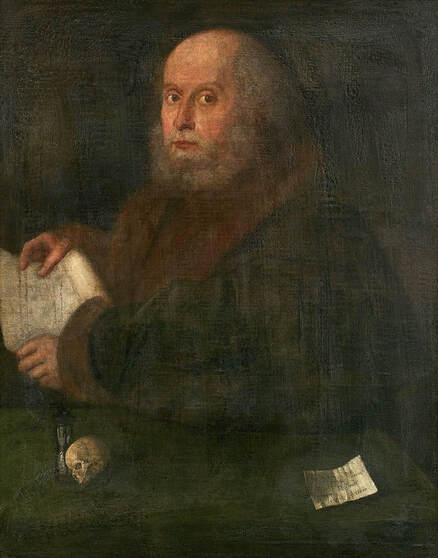

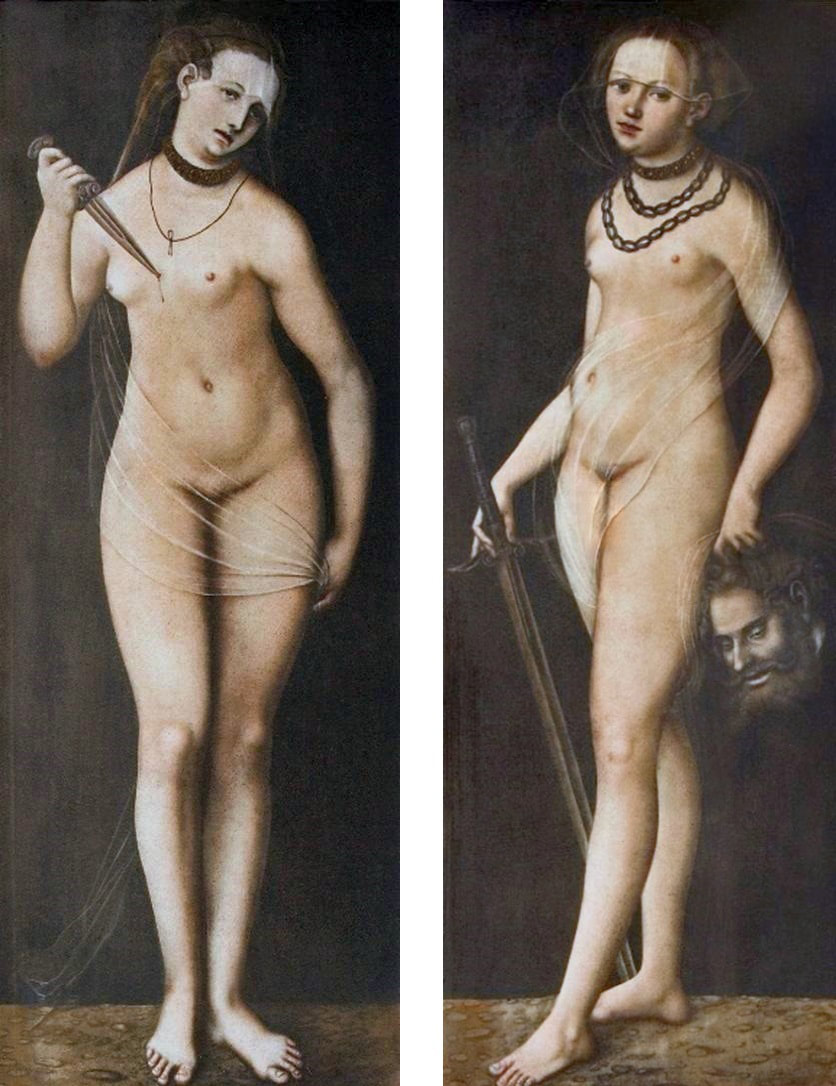

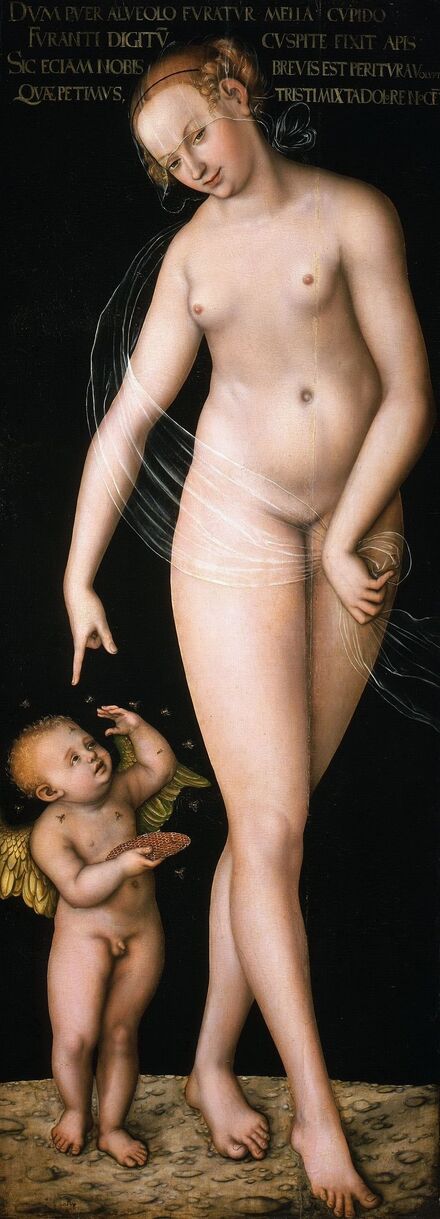

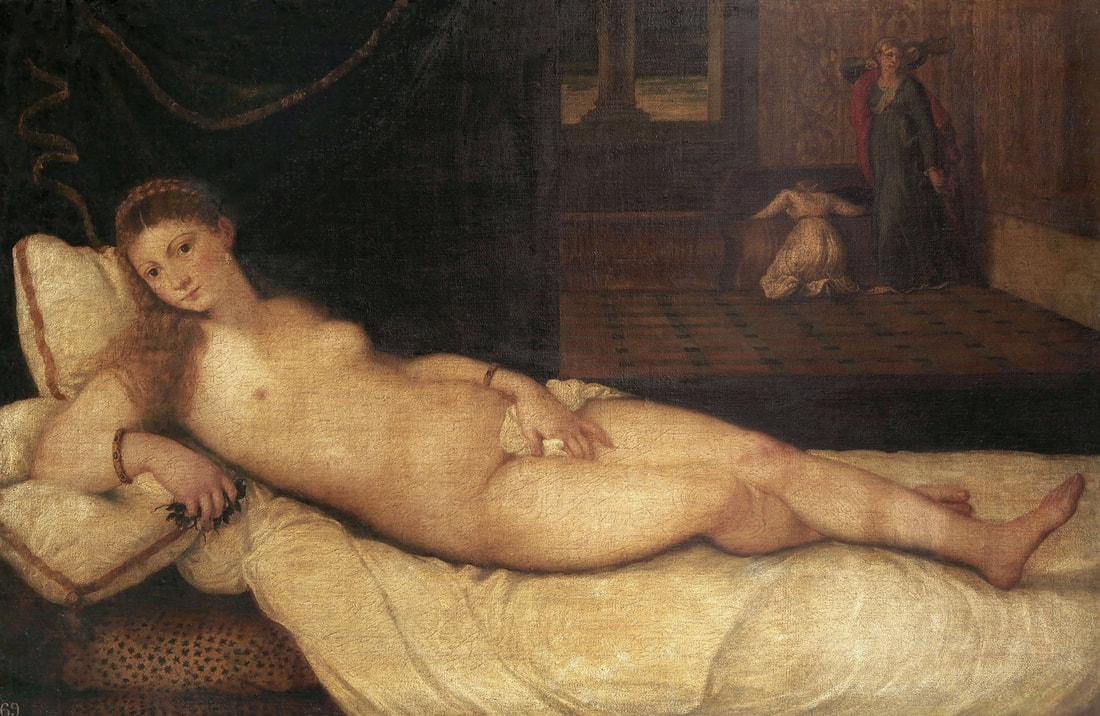

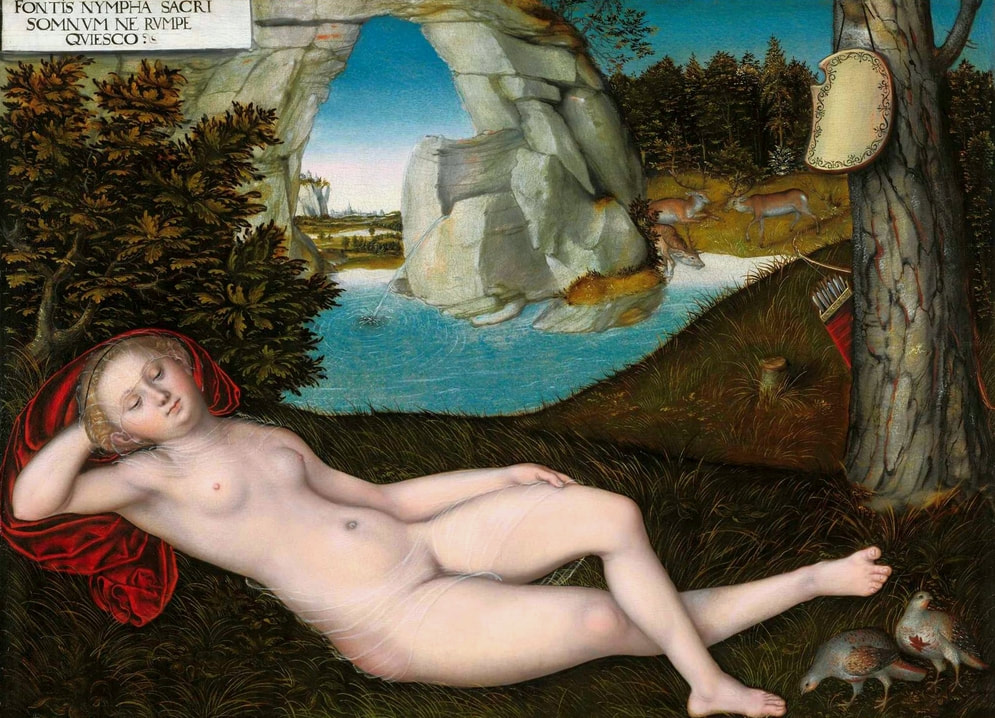

To attract suitable marriage proposal, Hedwig's father continued to amass a considerable dowry for her. He commissioned the most luxurious items in Poland and abroad, like the casket, created by Jacob Baur and Peter Flötner in Nuremberg in 1533, adorned with jewels from Jagiellon collection (Hermitage Museum). He also charged his banker Seweryn Boner with the acquisition in Venice of some lengths of silk, several hundred ells of satin, five cloth of gold bales, thirty bales of fine Swabian and Flemish linen as well as pearls for 1,000 florins. In her letter of 19 April 1535 the Princess asked her father for a larger amount of cloth of gold. The marriage was a political contract, and Princess' role was to seal the alliance between countries by producing offspring. Thanks to this she could also have some power in her new country and Hedwig's stepmother, Bona Sforza, knew perfectly about it. It was she who probably took care of providing some erotic items in Hedwig's dowry. In 1534 it was finally decided, in secret from Bona, who was unfavorable to the Hohenzollerns, that Hedwig will marry Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg and the marriage contract was signed on 21 March 1535. Sigismund commissioned some portraits of Hedwig from court painter Antonius (most probably Antoni of Wrocław), which were sent to Joachim. The groom arrived to Kraków with a retinue of 1000 courtiers and 856 horses and Sigismund's nephew Albert, Duke of Prussia with his wife Dorothea of Denmark and 400 people. Apart from 32,000 red zlotys in cash Hedwig also received from her father robes, silverware, "other indispensable utensils", money for personal use, as well as a rich bed with canopy (canopia alias namiothy), which she took with her to Berlin. A large painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder from about 1530 in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (oil on panel, 166.9 x 61.4 cm, inv. 594), which was transferred from the Royal Prussian Castles in 1829/1830, shows Hedwig as Venus and Cupid. The sitter's resemblance to the princess from her earlier portraits by Cranach, which I have identified, is undeniable - paintings in Veste Coburg (M.163) and Prague Castle (HS 242). This erotic painting was undeniably part of her dowry. A portrait from the same collection, which depicts Hedwig as Judith with the Head of Holofernes and dated 1531, was acquired from Suermondt collection in Aachen (oil on panel, 72 x 56 cm, inv. 636A). As the portraits of her stepmother, it most probably also has a political meaning, or the Princess just wanted to be depicted as her beautiful stepmother. Aachen was an Imperial City, where coronations of emperors were held till 1562 and in 1815, control of the town was passed to the Kingdom of Prussia. Already in 1523 Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg wanted Hedwig's hand for one of his sons. It is possible that her portrait as Judith was sent to the Hohenzollerns or to the Habsburgs already in 1531 to underline that the Jagiellons would not permit them to take their crown. A similar painting to that of Hedwig's, depicting Venus with Cupid stealing honey by Lucas Cranach the Elder and dated 1531, is in the Borghese Gallery in Rome (oil on panel, 169 x 67 cm, inv. 326). It was aquired in 1611 and bears the same inscription as effigy of Katarzyna Telniczanka as Venus. The woman has features of Hedwig's cousin Anna Jagellonica (1503-1547), Queen of Germany, Bohemia, and Hungary. Anna was a daughter of Vladislaus II, King of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, elder brother of Sigismund I, and his third wife, Anne of Foix-Candale. On 26 May 1521 she married Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, grandson of Emperor Maximilan I, who was elevated to the title King of the Romans by his brother Emperor Charles V in 1531. On her golden hairnet embroidered with pearls there is a monogram W.A.F.I. or W.A.F. which can be interpreted as Wladislaus et Anna (parents), Ferdinandus I (husband), Wladislaus et Anna Filia (daughter of Vladislaus and Anne) or Wladislaus et Anna de Fuxio (Vladislaus and Anne of Foix). Similar monogram of her parents WA is visible on a golden pendant at her hat in her portrait at the age of 16 by Hans Maler, created in 1520 (private collection). A portrait of Anna's husband, painted by Cranach in 1548, so after her death, is in Güstrow Palace (G 2486). The register of paintings of Boguslaus Radziwill (1620-1669) from 1657 (AGAD 1/354/0/26/84), which included several paintings by Cranach, lists: "Image of the Three Cupids", "Image of the Three Goddesses", "A picture of the Emperor's face on one side and Adam and Eve on the other by Lucas Cranach", "Judith" and "Lucas Cranach's art with Venus and Cupid". In his "Thoughts on painting" (Considerazioni sulla pittura), written between 1617 and 1621 in Rome, Italian physician and art collector Giulio Mancini (1559-1630), claimed that "lascivious paintings in similar places where a man stays with his wife are appropriate, because such a view is very beneficial for excitement and for making beautiful, healthy and vigorous sons" (pitture lascive in simil luoghi dove si trattenga con sua consorte sono a proposito, perché simil veduta giova assai all’eccitamento et al far figli belli, sani e gagliardi) (partially after "Ksiądz Stanisław Orzechowski i swawolne dziewczęta" by Marcin Fabiański, p. 60).

Portrait of Crown Princess Hedwig Jagiellon (1513-1573) as Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

Portrait of Crown Princess Hedwig Jagiellon (1513-1573) as Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

Portrait of Queen Anna Jagellonica (1503-1547) as Venus with Cupid stealing honey by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531, Borghese Gallery in Rome.

Portraits of Zofia Szydłowiecka by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop

On April 4, 1528, John Zapolya, elected King of Hungary, came to Tarnów in the company of Grand Crown Hetman and voivode of Ruthenia, Jan Amor Tarnowski (1488-1561). As a result of the double election and the lost battle with Archduke Ferdinand I near Tokaj, Zapolya sought a safe haven - first in Transylvania and then in Poland.

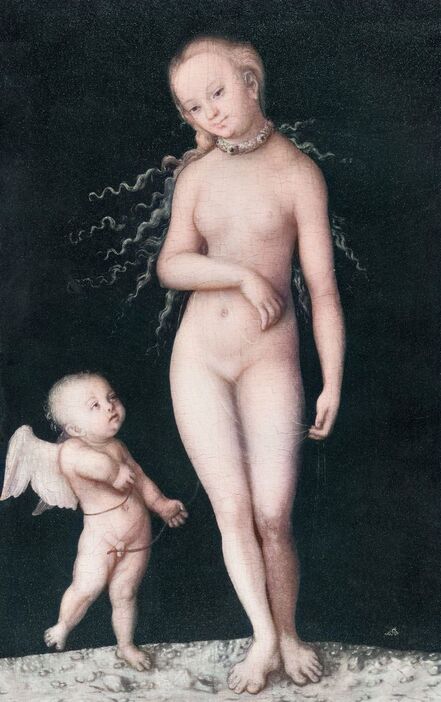

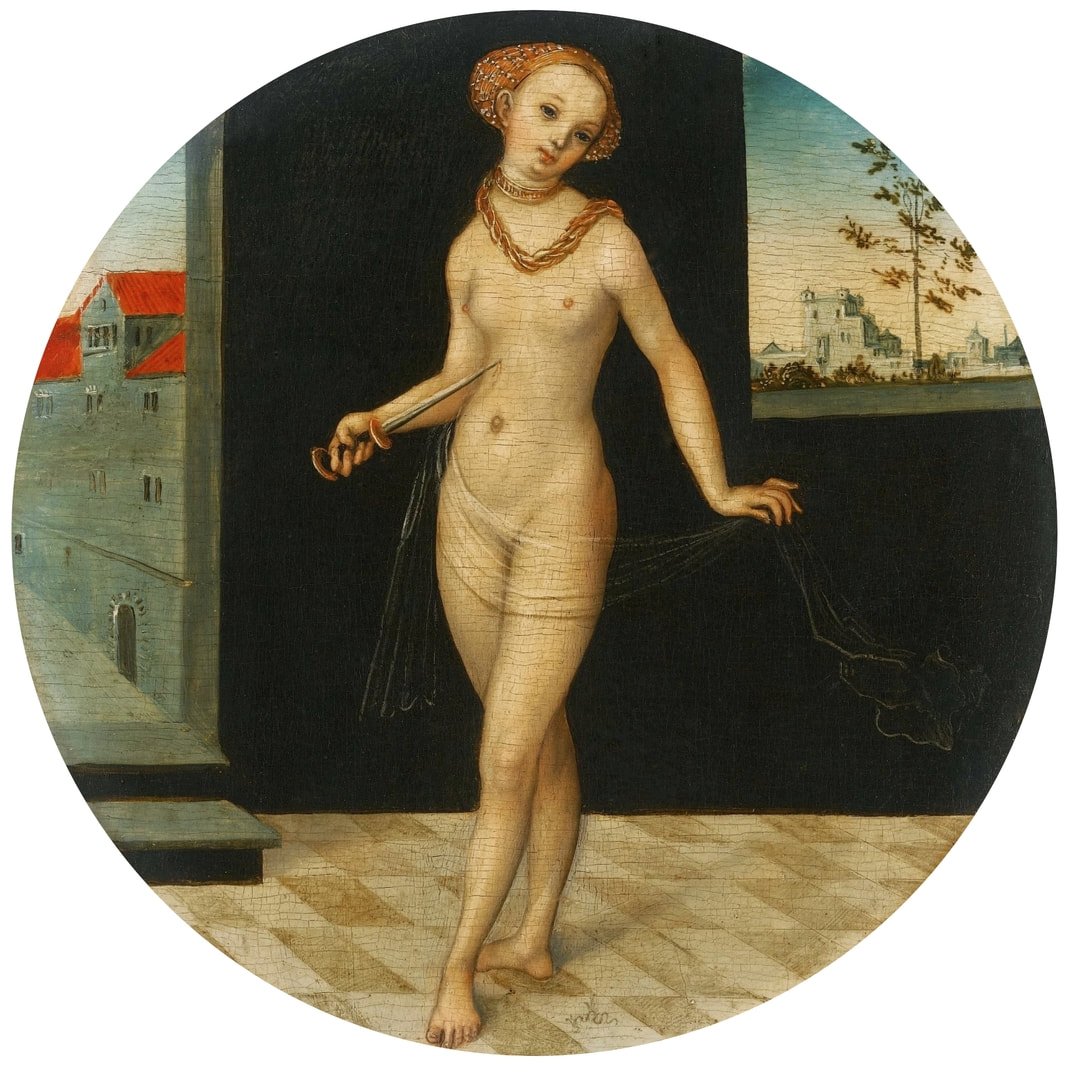

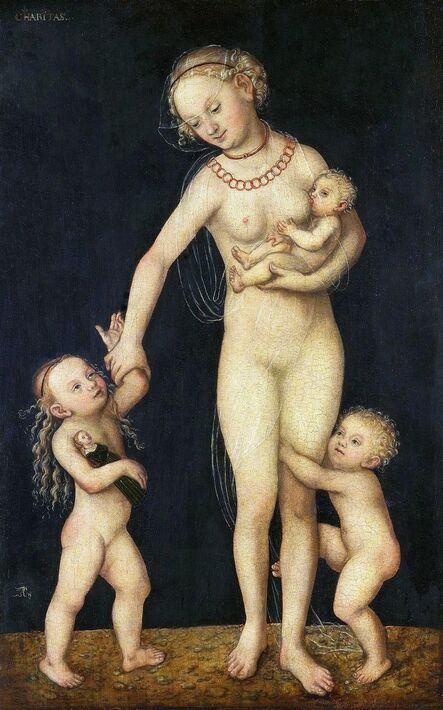

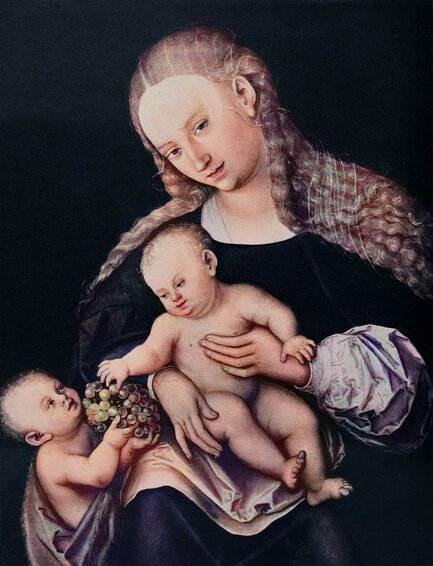

For the duration of his stay, Hetman Tarnowski made the entire castle and the city of Tarnów at his disposal, for which, he was severely reprimanded by Ferdinand I. To this, in a letter dated in Sandomierz on 25 July 1528, he was to reply that the holy laws of friendship did not allow him to refuse hospitality. From April to September 1528, the city became, under the patronage of Queen Bona, the seat of the Hungarian king and the center of activities aimed at restoring his throne. The Queen did it secretly so as not to reveal her role to the Habsburg agents. Zapolya sent ambassadors to Bavaria, King Francis I of France, the Pope and a number of other states. Finally he approached the Ottoman Porte and returned to Hungary on October 2, 1528. He expressed his gratitude for the hospitality of the people of Tarnów by granting a trade privilege and founding a beautiful altar for the collegiate church, not preserved. To the Hetman he offered a mace and a golden shield, estimated at 40,000 Hungarian red zlotys (after Andrzej Niedojadło's "Goście zamku tarnowskiego" and Przemysław Mazur's "Król Jan Zápolya w Tarnowie - Tarnów 'stolicą' Węgier"). On May 8, 1530 in the royal Wawel Cathedral, in the presence of the king and queen, the bishop of Kraków, Piotr Tomicki, celebrated the wedding of sixteen-year-old Zofia Szydłowiecka and forty-two-year-old (which was then considered an advanced age) Hetman Jan Amor Tarnowski. Zofia, born in about 1514, was the eldest daughter of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki (1467-1532), Great Chancellor of the Crown and Zofia Targowicka (ca. 1490-1556) of Tarnawa coat of arms. They had 9 children, but only three daughters reached adulthood. Szydłowiecki was a political opponent of Queen Bona and supporter of the Habsburgs - in 1527 he reported to his friend Albert of Prussia, that the Queen extended her influence to almost all spheres of political life. In addition to a luxurious lifestyle, for which he earned the name of the Polish Lucullus among his contemporaries, he was a patron of art and science and collected illuminated codices. Erasmus of Rotterdam dedicated his work "Lingua" to him, published in Basel in 1525. In 1530 the Crown Chancellor thanked to Jan Dantyszek for the portrait of Hernán Cortés that he sent to him, adding that the man's deeds are known to him ex libro notationum received as a gift from Ferdinand of Austria. After his death in 1532, Jan Amor Tarnowski, become the guardian of his younger daughters. In 1519, when his second daughter Krystyna Katarzyna, future duchess of Ziębice-Oleśnica was born, Krzysztof Szydłowiecki commissioned a votive painting, most likely, for the Collegiate Church of St. Martin in Opatów, where he also offered a portrait of Beatrice of Naples as Madonna and Child by Timoteo Viti or Lucas Cranach the Elder. This painting, attributed to Master Georgius, a painter apparently of Bohemian origin, was later in the collection of count Zdzisław Tarnowski in Kraków, now in the National Museum in Kraków (tempera and gold on wood, 60.5 x 50 cm, MNK I-986). It shows the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the founder kneeling and looking at the Virgin. His effigy, armour and attire are very similar to these visible in the miniature from the Liber geneseos illustris familiae Schidloviciae (The genealogical book of the Szydłowieckis) in the Kórnik Library, created by Stanisław Samostrzelnik in 1532. The effigy of Saint Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary, the protector of pregnant women and patron saint of families and children, on the right is very similar to the portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka née Goździkowska of Łabędź (Swan) coat of arms, mother of Krzysztof in the same Liber geneseos illustris familiae Schidloviciae. Also face features of Saint Anne are very similar to effigies of sons of Zofia Goździkowska - from the bronze tomb monument of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki in the Collegiate Church in Opatów, attributed to Bernardino Zanobi de Gianotis and marble tombstone of Mikołaj Stanisław Szydłowiecki (1480-1532) in Szydłowiec, created by Bartolommeo Berrecci or workshop, both from about 1532. Consequently the woman depicted as the Virgin must be Zofia Targowicka, wife of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki. A similar woman to the effigy of the Virgin from Szydłowiecki's votive painting was depicted as Madonna and as Venus in two small paintings, both by Lucas Cranach, his son or workshop. The image of Venus, today in private collection (wood, 42 x 27 cm), had been in the collection of Munich art dealer A.S. Drey, before being acquired by the Mogmar Art Foundation in New York in 1936. It is similar to effigies of Beata Kościelecka and Margaret of Brandenburg (1511-1577), Duchess of Pomerania as Venus, therefore should be dated to around 1530, when Zofia Szydłowiecka, the eldest daughter of Krzysztof was about to get married. The Madonna with similar face was purchased from Monsignor J. Shine on April 1954 by the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin (transferred to linen, attached to plywood, 72.3 x 49.5 cm, NGI.1278). A miniature tondo from the collection of Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon de Fabregoules (1746-1836), offered to the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence by his sons in 1860 (wood, 14 cm, inv. 343), shows her in a dress and pose similar to that of Queen Bona in a miniature sold at Hôtel Drouot in Paris on 30 October 1942. The same woman was also depicted as Judith with the head of Holofernes in a painting by workshop Lucas Cranach the Elder, similar to the portrait of Queen Bona in Vienna and in Stuttgart. This painting was acquired by William Delafield in 1857 and was sold in London in 1870 (wood, 39.7 x 26.7 cm). Her face is very similar to the portrait of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki in the Liber geneseos illustris familiae Schidloviciae. If the portrait as Judith was a political statement of support of the Queen's policies and not a whim of a young girl willing to emulate the Queen, this will add a further explanation to a series of caricature portraits of this girl in the arms of an ugly, old man. One of the best of these caricature portraits is in the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf (wood, 38.8 x 25.7, M 2248). Before 1860 it was in the collection of Count August von Spee (1813-1882) from an old Rhenish noble family from the Archdiocese of Cologne, while the Archbishop of Cologne was one of the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire. On 5 January 1531 Ferdinand of Austria had been elected the King of the Romans and so the legitimate successor of the reigning Emperor, Charles V, who was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor in 1530. A workshop copy of this painting from the collection of Baron Samuel von Brukenthal (1721-1803), a personal advisor of Empress Maria Theresa, is in the Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Transylvania (wood, 37.4 x 27.6 cm, inv. 218). Brukenthal came from Transylvanian Saxon lesser nobility, while the Saxons were partisans of Ferdinand of Austria and supported the House of Habsburg against John Zapolya. Several other copies of this composition exist. The girl was also depicted in another version of the scene, kissing the old man, in the National Gallery in Prague (wood, 38.1 x 25.1 cm, O 455). It was bequeathed by Dr. Jan Kanka in 1866 and its earlier history is unknown. This work of fairly high standard, may have been produced by the master himself. On 24 October 1526 the Bohemian Diet elected Ferdinand King of Bohemia under conditions of confirming traditional privileges of the estates and also moving the Habsburg court to Prague. We can assume with high probability that the paintings were commissioned by partisans of Ferdinand I or even by himself, dissatisfied that the eldest daughter of Szydłowiecki joined the camp of his opponent, "a great enemy of the king of Rome" Queen Bona (as later reported an anonymous Habsburg agent at the Polish court in an encrypted message). It is possible that the painting "A woman courted by the old man", mentioned in the register of paintings of Boguslaus Radziwill (1620-1669) from 1657 (AGAD 1/354/0/26/84), where there were several paintings by Cranach, was another version or a copy of one of these two compositions. She was also depicted in another painting by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder from the early 1530s, in guise of Lucretia, legendary heroine of ancient Rome, just before she commits suicide, now in the Historical Museum in Regensburg (wood, 62 x 41 cm, LG 14). The painting was purchased from the Swiss art market by Hermann Göring in 1942. Seized by the Allies after the World War II, it was acquired by the Federal Republic of Germany. Her splendid gown, open at the front and revealing her naked chest, is similar to those visible in the miniatures of Barbara Tarnowska née Szydłowiecka and Anna Szydłowiecka née Tęczyńska from the mentioned Liber geneseos. The castle behind on a fantastic rock is undoubtedly one of the Tarnowski mansions in mythical disguise, possibly the favorite residence of Jan Amor Tarnowski in Wiewiórka near Dębica, who died there in 1561. This cannot be confirmed with certainty because the opulent residence in Wiewiórka was almost completely destroyed and no confirmed view of the castle preserved. This defensive manor on a hill surrounded by a moat, had at least one tower and a drawbridge, as well as barrel vaulted cellars, which preserved. Many important political and cultural figures of 16th-century Poland visited the court in Wiewiórka, and in 1556 a meeting of the hetman's supporters was held there, during which postulates of religious reforms for the next Sejm were drafted, including, among others, the marriage of priests.

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne with portraits of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, his wife Zofia Targowicka and mother Zofia Goździkowska by Master Georgius, 1519, National Museum in Kraków.

Portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) as Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Lucas Cranach the Younger or workshop, ca. 1530, Private collection.

Portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) as Madonna and Child with Infant John the Baptist and angels by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Lucas Cranach the Younger or workshop, ca. 1530 or after, National Gallery of Ireland.

Miniature portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530, Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence.

Portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) as Judith with the head of Holofernes by workshop Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530, Private collection.

Ill-Matched Couple, caricature of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) and her husband by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop, ca. 1530, Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf.

Ill-Matched Couple, caricature of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) and her husband by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530, Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu.

Ill-Matched Couple, caricature of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) and her husband by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop, ca. 1530, National Gallery in Prague.

Portrait of Zofia Szydłowiecka (1514-1551) as Lucretia by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1532, Historical Museum in Regensburg.

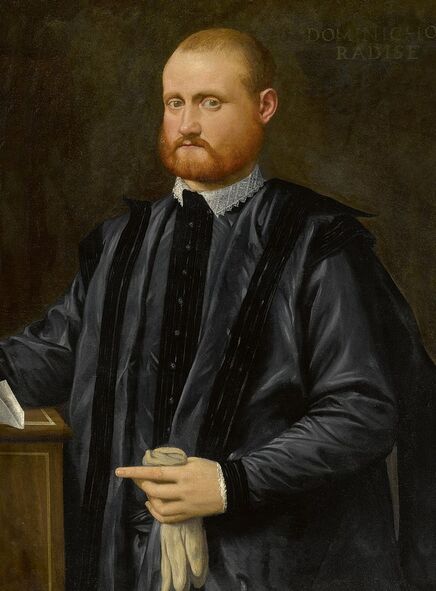

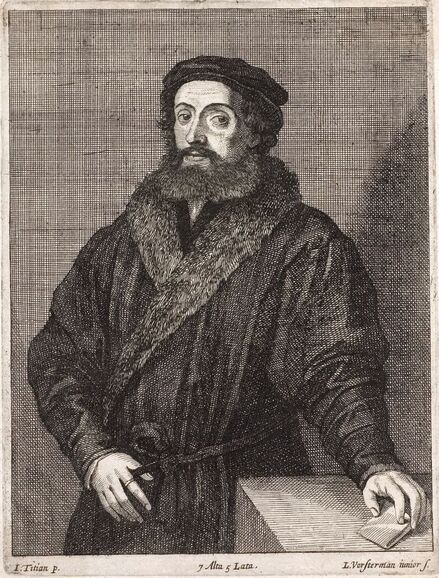

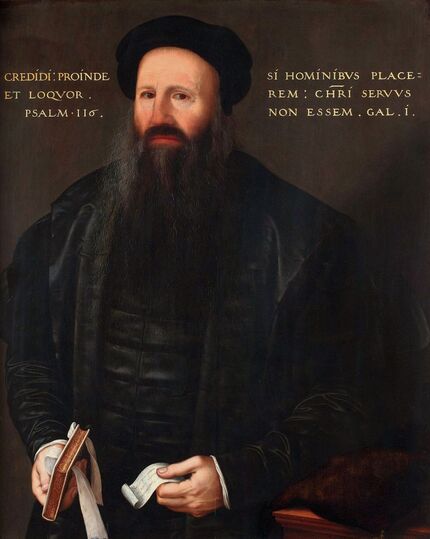

Portrait of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, Great Chancellor of the Crown by Titian

"I am a great admirer of beautiful and artistic paintings" (Ego multum delector in pulcra et artificiosa pictura), wrote Krzysztof Szydłowiecki (1467-1532), Vice-Chancellor of the Crown, in a letter of May 17, 1512 from Toruń to Fabian Luzjański, Bishop of Warmia. He asked for help in obtaining from Flanders via Gdańsk the painting of the Madonna Monstra te esse Matrem ("Show thyself a mother").

From 1496 Szydłowiecki was a courtier of Prince Sigismund and from 1505 he was a marshal of the prince's court. From the moment of the coronation of Sigismund I, Krzysztof occupied various important positions and he become the Great Chancellor of the Crown in 1515. He managed Polish foreign policy during the reign of Sigismund I. In 1515, together with Bishop Piotr Tomicki, he developed an agreement with the Habsburgs, which was signed during the Congress of Vienna and Emperor Maximilian I, as a sign of respect and gratitude, granted Krzysztof the title of baron of the Holy Roman Empire (he rejected the princely title offered to him by the emperor). Thanks to numerous grants, as well as bribes (from Emperor Maximilian alone, he accepted 80,000 ducats for supporting Austria at the congress of monarchs in Vienna, and also took money from the monarch of Hungary, John Zapolya, and Francis I of France; the city of Gdańsk also paid for the protection), he made a huge fortune. The chancellor died on December 30 , 1532 in Kraków, and was buried in the collegiate church in Opatów. His tombstone, decorated with a bronze bas-relief, was made in the workshop of Bartolommeo Berrecci and Giovanni Cini in Kraków. He ordered the tombstone for himself during his lifetime and after his death, in about 1536, on the initiative of his son-in-law Jan Amor Tarnowski (1488-1561), it was enlarged by adding a bas-relief depicting relatives and friends moved by the news of the chancellor's death, on the pedestal of the monument (so-called Opatów Lamentation). Szydłowiecki imitated the luxurious lifestyle of Prince Sigismund, who in 1501 ordered several illuminated prayer books (or one book adorned by several illuminators), and the following year bought paintings with views of different buildings from Italian merchant (Ilalo qui picturas edificiorum dno principi dedit 1/2 fl.). Despite being a political opponent of Queen Bona, he followed the example of the queen, who at her court employed Italian painters and imported paintings from Italy for her vast collection (after "Bona Sforza" by Maria Bogucka, p. 105). His splendid castle on the island in Ćmielów, rebuilt in renaissance style between 1519-1531, was destroyed in 1657 by Swedish and Transylvanian forces, which also massacred many noble families who had taken refuge there (after "Encyklopedia powszechna", Volume 5, p. 755). This veritable Apocalypse, known as the Deluge (1655-1660), as well as other invasions and wars, left very little trace of the chancellor's patronage. Before 1509, Krzysztof's brother Jakub Szydłowiecki, Grand Treasurer of the Crown, brought from Flanders a "masterly made" painting of the Madonna (after "Złoty widnokrąg" by Michał Walicki, p. 108). In 1515 the chancellor offered to the Collegiate Church in Opatów a painting of Madonna and Child (disguised portrait of Beatrice of Naples, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia) by Timoteo Viti or Lucas Cranach the Elder, and in 1519 Master Georgius created a portrait of Krzysztof as a donor (National Museum in Kraków, MNK I-986). More than a decade later, in 1530, the chancellor received from Jan Dantyszek the portrait of Hernán Cortés, most likely by Titian, and a portrait of the chancellor was mentioned in the vault of the Nesvizh Castle in the 17th century. Most likely in Venice, in 1515 or after, Krzysztof acquired Legenda aurea sive Flores sanctorum by Jacobus de Voragine for his library (a printed bookplate with his coat of arms is on the back of the front cover), today in the National Library of Poland (Rps BOZ 11). It was created in the 1480s for Francesco Vendramini from Venice and illuminated by miniaturists active in Padua and Venice. In 1511, one of Poland's finest Renaissance painters and miniaturists, Stanisław Samostrzelnik, who also worked for the royal court, became his court painter (pictori nostro) and chaplain, and in this capacity he accompanied Szydłowiecki on his travels. Stanisław probably stayed with his patron in 1514 in Buda, where he became familiar with the Italian Renaissance. He decorated documents issued by the chancellor, such as the privilege of Opatów of August 26, 1519, with the portrait of the chancellor as a kneeling donor, wearing a fine gold-engraved armor and a crimson tunic. Shortly before the chancellor's death, he began working on a series of miniature portraits of members of the Szydłowiecki family, known as Liber geneseos illustris familiae Schidloviciae (1531-1532, Kórnik Library), including the effigy of the chancellor in another beautiful armour decorated with gold and crimson tunic. Earlier, in 1524, Samostrzelnik illuminated the Prayer Book of Szydłowiecki, adorned with chancellor's coat of arms in many miniatures. It is dated (Anno Do. MDXXIIII) and has a painted bookplate. The manuscript was disassembled at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Probably a Milanese antiquarian cut out miniatures from it, some of which, in the number of ten, were acquired by Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (F 277 inf. no 1-10), while the manuscript, divided into two parts and acquired by the City of Milan from the library of the princes of Trivulzio, is kept in the Archivio Storico Civico (Cod. no 459, Cod. no 460). One miniature, the Flight into Egypt, is largely inspired by a painting by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, created in 1511 for the Skałka Monastery in Kraków. The others could derive from paintings in the Szydłowiecki collection or the royal collection - the Massacre of the Innocents, reminiscent of Flemish paintings and the Madonna and Child, in a manner that brings to mind the Italian paintings. The prayer book is one of the two important polonica of the Jagiellonian period in Milan. The other is also in Ambrosiana, in a part dedicated to art collection - Pinacoteca. It is a sapphire intaglio with bust of Queen Bona Sforza, attributed to Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio (inventory number 284). If not for the Latin inscription on her dress (BONA SPHOR • REG • POLO •), it would be considered to represent an Italian princess, which is generally correct. The exact provenance of these two works of art is unknown, so we cannot rule out the possibility that they were diplomatic gifts to Francesco II Sforza (1495-1535), the last member of the Sforza family to rule Milan, and Bona's relative. The ruling houses of Europe exchanged such gifts and effigies at that time, including the portraits of important notables. In the same Ambrosiana in Milan there is also a portrait of an old man in armour by Titian (oil on canvas, 65 x 58 cm, inventory number 284). It is dated around 1530, the time when Chancellor Szydłowiecki received a portrait of the Spanish conquistador, most likely by Titian. The work arrives in Ambrosiana together with the nucleus donated in 1618 by Cardinal Federico Borromeo who in the Musaeum reports that "Titian would have liked to paint his father like this, in armour, to jokingly celebrate the nobility he said he had achieved with such an offspring" (Tiziano avrebbe voluto dipingere suo padre così corazzato, per celebrare scherzosamente la nobiltà che egli diceva di aver conseguito con una tale prole). "Jokingly", because the old man's truly lordly attire and pose do not suit the simple clerk that was Titian's father, Gregorio Vecellio. He held various minor posts in Cadore from 1495 to 1527, including that of an officer in the local militia and, from 1525, superintendent of mines. We should doubt that anyone really wanted to joke around with their father like that, especially a respected painter such as Titian, thus this suggestion has not convinced art historians of the identity of the model. The man in the portrait wears costly armour etched with gold and a crimson velvet tunic, known as a brigandine, a garment usually made of thick fabric, lined inside with small oblong steel plates riveted to the fabric. Very similar velvet brigandine in the Royal Armoury (Livrustkammaren) in Stockholm (LRK 22285/LRK 22286), is considered as a war booty from Warsaw (1655), just like another, larger (23167 LRK). Szydłowiecki's son-in-law, Jan Amor Tarnowski, was depicted in armour with crimson brigandine and holding a baton in a painting by circle of Jacopo Tintoretto (Private collection). The sitter in Ambrosiana painting is also holding a miltary baton, that is traditionally the sign of a field marshal or a similar high-ranking military officer. Chancellor Szydłowiecki is generally not considered an important military commander, like Tarnowski, but he held several military positions, such as the castellan of Kraków (1527-1532), who commanded the nobility of his county during a military campaign (after "Ksie̜ga rzeczy polskich" by Zygmunt Gloger, p. 153-154), and in all mentioned effigies by Samostrzelnik, as well as in his tombstone, he was portrayed like an important military officer. The age of the sitter also matches the age of the chancellor, who was 64 in 1530. Finally, the man in the portrait bears a strong resemblance to Szydłowiecki as represented in a medal by Hans Schwarz from 1526 (The State Hermitage Museum, ИМ-13497). The Chancellor's characteristic facial features, a pointed nose and protruding lower lip, are similar to those of his tombstone effigy, his portraits by Master Georgius and Samostrzelnik (Liber geneseos ...), as well as in the marble tombstone of his brother Mikołaj Stanisław (1480-1532) by Bartolommeo Berrecci or workshop, founded by Krzysztof (Saint Sigismund's church in Szydłowiec). It is not without reason that Szydłowiecki was known as the Polish Lucullus, in memory of a Roman general and statesman famous for his lavish lifestyle.

Portrait of Krzysztof Szydłowiecki (1467-1532), Great Chancellor of the Crown in armour with crimson brigandine and holding a baton by Titian, ca. 1530, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

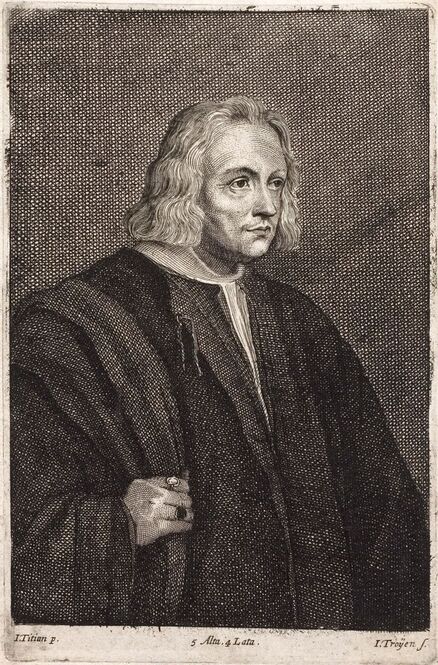

Portrait of Hernán Cortés by Titian or circle

Around 1529 King Ferdinand of Austria, personally handed (manu porrexit et dedit) to Chancellor Krzysztof Szydłowiecki an interesting book written in Latin with the words: "that what is written in it should be believed as in the Gospels". It was the work of the conqueror of Mexico, Hernán Cortés (Ferdinandus Corthesius), containing a description of his deeds, Liber narrationum. In 1529, Cortés, who arrived in Europe in 1528, stayed at the imperial court to personally justify himself for accusations of various kinds of abuse. On this occasion he presented his monarch with the gifts of a new world, and next to them, the greatest peculiarity for Europe, the Indians. In a letter of July 23, 1529 from Kraków (Acta Tomiciana, XI / 287) chancellor Szydłowiecki even asked the Polish envoy Jan Dantyszek, who was staying at the court of Charles V to bring him an Indian. "The glorious deeds" of Cortés, a man singularis et magnanimi, as Szydłowiecki writes to Dantyszek, apparently interested him keenly since he sought the "image" (effigies) of the famous Spaniard, according to letter of 27 April 1530 (Acta Tomiciana, XII / 110), and he also received it from Dantyszek (after "Kanclerz Krzysztof Szydłowiecki ..." by Jerzy Kieszkowski, Volume 3, pp. 336, 618-619).

During his stay in Spain in 1529, Cortés obtained from Charles V the title of Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca and the government over future discoveries in the South Sea and returned to Mexico in 1530. At that time, Dantyszek accompanied the Emperor on his journey from Barcelona (July 1529) through Genoa and Piacenza to Bologna - the place of the coronation, where the court stopped for a longer time and where Dantyszek stayed from the autumn of 1529 to the spring of 1530. The next longer stop was in Mantua, from where, after May 30, he set out with the imperial court through Trento and Innsbruck to Augsburg, where the emperor met his brother Ferdinand I and where Dantyszek stayed until the beginning of December 1530, taking part in the Imperial Diet (after "Itinerarium Jana Dantyszka" by Katarzyna Jasińska-Zdun, p. 198). It is said that in 1530, Titian was invited to Bologna by Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici, through the agency of Pietro Aretino. There he made a most beautiful portrait of the Emperor showing him in armour holding a commander's baton, according to Vasari's "Lives of the Artists" (confirmed by a letter dated 18 March 1530 from Giacomo Leonardi, ambassador of the Duke of Urbino to the Republic of Venice), considered lost. According to other authors, they did not meet in person in 1530 (after "The Earlier Work of Titian" by Sir Claude Phillips, p. 12), while a number of art historians are insisting that the painter must have seen the sitter to paint a portrait and attributing errors to Vasari. However, it is also likely that Titian created his portrait based on a preparatory drawing by another artist who was in Bologna. In 1529 Christoph Weiditz, a German painter and medalist, active mainly in Strasbourg and Augsburg (he went to the royal court in Spain in 1528-1529), created a bronze medal of Cortés at the age of 42 (DON·FERDINANDO·CORTES·M·D·XXIX·ANNO·aETATIS·XXXXII). It should be noted that the similarity of the model with the most famous images of Cortés is quite general. That same year and around Weiditz also created a medal of Jan Dantyszek and of Elisabeth of Austria (d. 1581), illegitimate daughter of Emperor Maximilian I (after "Artyści obcy w służbie polskiej" by Jerzy Kieszkowski, p. 15). There is no mention of any precious material, such as gold or silver, regarding the "image" of the Spanish conquistador for Szydłowiecki, so it was most likely a painting commissioned in Italy from an artist close to the Imperial court. Dantyszek was renowned for his artistic taste and commissioned and received exquisite works of art. Conrad Goclenius, the closest confidant of humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, thanks to Dantyszek's support received a rich beneficium and various gifts from him: furs, bas-reliefs, his portrait, for which he gave Dantyszek a portrait of Erasmus painted by Holbein (In praesentia in ejus rei symbolum mitto tibi dono effigiem D. Erasmi Roterodami, ab Ioanne Holbeyno, artificumin - wrote Goclenius in a letter of April 21, 1531 from Leuven), a bust of Charles V and others, which were part of a later rich collection at the ducal residence of Dantyszek in Lidzbark (after "Jan Dantyszek - człowiek i pisarz" by Mikołaj Kamiński, p. 71). In a letter to Piotr Tomicki of March 20, 1530, Dantyszek sadly informed that for eighty ducats he sold to Anton Welser an emerald received from Prince Alfonso d'Este during his stay in Ferrara in 1524, which he intended to give to the addressee, to the wife of Helius Eobanus Hessus he offered a chain and pearls set in gold, a Spanish horse to Piotr Tomicki, gold (or ducats) from Spain to his friend Jan Zambocki, earrings or rings (rotulae), unspecified handicrafts of Spanish women and scissors or pliers (forpices) to Queen Bona, and expensive silk fabrics and gold coins with images of rulers to Johannes Campensis (after "Itinerarium Jana Dantyszka", pp. 224, 226). In April 1530, when he sent his letter to Szydłowiecki, Dantyszek was in Mantua and the most important effigies of Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua created at that time were painted by Titian - in 1529 and 1530, one is in Prado in Madrid (inventory number P000408, after "El retrato del Renacimiento", pp. 215-216). Therefore, the diplomat must have commissioned or purchased a painting from the Venetian master. On October 29, 2019 a portrait of gentleman (Retrato de caballero) by Italian school was sold in Seville, Spain (oil on canvas, 58 x 48 cm, Isbilya Subastas, lot 62). This portrait is almost an exact, reduced version of a painting attributed to Peter Paul Rubens (oil on canvas, 121.5 x 101 cm, The Courtauld Gallery in London), painted between 1608-1612, a copy of a painting by Titian which the painter probably saw in Mantua. Other copy, attributed to Jan Steven van Calcar, is in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar (G49). An engraving by George Vertue dated 1724 bears an inscription identifying the sitter as Hernán Cortés and the artist as Titian (HERNAN CORTES. Ex pictura TITIANI or Titian pinx - Scottish National Portrait Gallery, FP I 38.1 or British Museum, R,7.123). The same effigy was also reproduced as Cortés by Titian in Historia de la conquista de México, published in Madrid in 1783 - engraving by Fernando Selma (HERNAN CORTES. Titian Vecel pinx. / Ferdin Selma. sc.). The style of the painting sold in Seville is indeed close to Titian and his entourage, in particular Bonifazio Veronese, hence it is a one of a series of similar effigies ordered in Venice, the lost painting from the Gonzaga collection in Mantua copied by Rubens being probably a prototype. The man in the described portrait resembles the effigy of the Spanish explorer and conqueror of Mexico, published in Academie des sciences et des arts … by Isaac Bullart in 1682 (Volume 2, p. 277, National Library of Poland, SD XVII.4.4179 II), his portrait in the Museum of Cultures of Oaxaca (Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca) in Santo Domingo, Mexico and a likeness from the Portrait Gallery of the Viceroys (series in the Salon de Cabildos, Palacio del Ayuntamiento), both most probably from the 17th century. Cortés died on December 2, 1547 in Castilleja de la Cuesta near Seville. Consequently, the painting made around 1530 for Chancellor Szydłowiecki was most likely a copy of the described painting, possibly by Titian himself, as it was a gift for one of the most important people in Poland-Lithuania.

Portrait of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) by Titian or circle, ca. 1530, Private collection.

Portrait of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) by Jan Steven van Calcar after Titian, ca. 1530, Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

Portrait of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) by Peter Paul Rubens after Titian, 1608-1612, Courtauld Gallery in London.

Portraits of Princes of Ostroh by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop

Soon after death of Constantine, Prince of Ostroh king Sigismund had to deal with the quarrel between his son and his stepmother over the fabulous inheritance. Prince Ilia took the body of his father to Kiev, where he was buried in the Chapel of Saint Stephen of the Pechersk Lavra with great splendor. Already in 1522 his father assured him the succession to the starost of Bratslav and Vinnytsia, confirmed by the privilege of the king Sigismund issued at Grodno Sejm, "on Friday before Laetare Sunday 1522".

Then Prince Ilia sent from Kiev one hundred horsemen to the Turov Castle, on which a dower of his stepmother was secured. They took the castle by force, they sealed all things in the treasury, as well as privileges and even the testament of the deceased prince, handing them over to Turov governor. Alexandra's brother, Prince Yuri Olelkovich-Slutsky (ca. 1492-1542), intervened with the king, who sent his courtier to Prince Ilia, ordering him to return the castle and to pay a dowry of his sister Sophia: "As for Princess Alexandra's daughter, she [mother] is not to give her the third part of the dowry or the trousseau; but her brothers, Prince Ilia and the son of Princess Alexandra, Prince Vasily, her daughter, and their sister to equip and pay her dowry" (royal decree issued on August 5, 1531 in Kraków). In 1523, when he was twelve years of age, Ilia's father enaged him to a five-year-old daughter of his friend George Hercules Radziwill, Anna Elizabeth (1518-1558). George Hercules obtained a dispensation from Pope Clement VII as the groom was baptized and brought up in the "Greek rite". After death of his father the young prince lived in Kraków at the royal court, where he studied Latin and Polish. In 1530, 1531 and 1533 he fought with the Tatars and between 1534-1536 he took part in the Muscovite-Lithuanian war where he commanded his own armed forces. In 1536 Radziwill demanded that Ilia fulfill the contract, he however refused to marry Anna Elizabeth or her sister Barbara, citing the lack of his own consent and because he fell in love with Beata Kościelecka, a daughter of king's mistress. In a document issued on December 20, 1537 in Kraków king Sigismund released him from this obligation. "Prince Ilia falls from one mud to another", wrote to Albert of Prussia, royal courtier Mikołaj Nipszyc (Nikolaus Nibschitz), who also very negatively characterized liberated daughters of George Hercules Radziwill, about the planned marriage of Ilia with Kościelecka. The engagement with Beata was sealed with the royal blessing on January 1, 1539, and the wedding, on February 3 of the same year, was held at the Wawel Castle, one day after the wedding of Isabella Jagiellon and John Zapolya, King of Hungary. After the wedding ceremony, a jousting tournament was organized, in which Ilia took part. The prince wore silver armor lined with black velvet, a Tatar belt and leather shoes with spurs and silver sheets. During a duel with young king Sigismund Augustus, Ilia fell from his horse and suffered severe injuries. On August 16, 1539 in Ostroh, he signed his last will in which he left his possessions to the unborn child of Beata, a daughter born three months later. By virtue of the judgment of August 1531 Princess Alexandra was granted the towns of Turov and Tarasovo in today's Belarus and Slovensko, near Vilnius. As a wealthy widow in her late 20s, she most probably lived with her stepson in Kraków and in Turov. A painting by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder dated '1531' below inscription in Latin, most probably the first approach to this subject by Cranach, shows a courtly scene of Hercules and Omphale. A young man in guise of mythical hero is flanked by two noblewomen as Omphale's ladies. Partridges, a symbol of sexual desire hangs over the heads of the women. In the myths Omphale and Hercules became lovers and they had a son. The painting is known from several versions, all by Cranach's workshop as original, likely to be by the master's hand, is considered lost. One copy was reported before 1891 in the Wiederau Castle, built between 1697 and 1705 in a village south of Leipzig by David von Fletscher, a merchant of Scotish origin, royal Polish and electoral-Saxon privy and commercial councilor. The other was owned by the Minnesota Museum of Art until 1976, and another was sold in Cologne in 1966. There is also a version which was sold in June 1917 in Berlin together with a large collection of Wojciech Kolasiński (1852-1916), a minor Polish painter better known as an art restorer, collector, and antiquarian of Warsaw (Sammlung des verstorbenen herrn A. von Kolasinski - Warschau). The audacious woman on the left has just put a woman's cap on the head of a god of strength dressed in a lion's skin. Her bold pose is very similar to that visible in a portrait of Beata Kościelecka, created by Bernardino Licinio just a year later. Also her face features resemble greatly other effigies of Beata. The woman on the right bears the features of Princess Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska, the young man is therefore Prince Ilia, who just returned from a glorious expedition against Tatars. Princess Alexandra, a beautiful young woman, like Queen Bona and Beata Kościelecka, also deserved to be represented in "guise" of the goddess of love - Venus. A small painting of a nude woman by Lucas Cranach the Elder, acquired by Liechtenstein collection in 2013, and sometimes considered a fake, is dated '1531' and the woman resemble greatly Princess Alexandra. This work predates by one year a very similar Venus in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.

Portrait of Beata Kościelecka, Ilia, Prince of Ostroh and Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska as Hercules and Omphale's maids from the Kolasiński collection by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531, Private collection.

Portrait of Beata Kościelecka, Ilia, Prince of Ostroh and Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska as Hercules and Omphale's maids from Cologne by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531, Private collection.

Portrait of Beata Kościelecka, Ilia, Prince of Ostroh and Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska as Hercules and Omphale's maids from Minnesota Museum of Art by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1531, Private collection.

Portrait of Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska, Princess of Ostroh nude (Venus) by Lucas Cranach the Elder or workshop, 1531, Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna.

Portrait of Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska, Princess of Ostroh nude (Venus) by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, Städel Museum in Frankfurt.

Portrait of Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska by Bernardino Licinio

The number of portraits by Licinio that can be associated with Poland and Lithuania allows us to conclude that he became the favorite painter of the Polish-Lithuanian royal court in Venice in the 1530s, especially of Queen Bona, Duchess of Bari and Rossano by her own right. It seems also that portraits were commissioned in Licinio's and Cranach's workshops at the same time as some of them bear the same date (like the effigies of Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski). Fashion in the 16th century was an instrument of politics, so in portraits for German "allies" the model was depicted dressed more in German style and for Italian "allies" in Italian style, with exceptions like the portrait of Queen Bona by Cranach in Florence (Villa di Poggio Imperiale) or her portrait by Giovanni Cariani in Vienna (Kunsthistorisches Museum).

After death of his father in 1530 Prince of Ostroh, Constantine Vasily (1526-1608), the younger son of Grand Hetman of Lithuania, was brought up in Turov by his mother Princess Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska, who administered the lands on behalf of her minor son. On January 15, 1532, the king ordered Fyodor Sangushko (d. 1547), starost of Volodymyr and Ivan Mykhailovych Khorevitch, starost of Queen Bona in Pinsk, to be commissioners for the implementation of the agreements reached between Ilia, Constantine Vasily's elder brother, and Alexandra. In 1537 a royal privilege to trade in Tarasov was issued in her name. Unlike other children of wealthy magnates Constantine Vasily did not travel to Europe and did not study in European universities. It is believed that his education was entirely at home. In particular, Constantine Vasily was taught by a tutor well versed in Latin and his home education was quite thorough, as evidenced by his subsequent great cultural and educational activity and knowledge of other languages (apart from Ruthenian, he knew Polish and Latin). At that time, it was much more important for the sons of magnates to acquire military knowledge and skills than to master languages and arts of discourse, especially this concerned the families of border officials, whose possessions constantly suffered from Tatar attacks. As important landowners Alexandra and her son were undoubtedly frequent guests at the multicultural, itinerant royal court in Lviv, Kraków, Grodno or Vilnius, where they could also meet many Italians, like the royal architect and sculptor Bernardo Zanobi de Gianottis, called Romanus. In a letter written in Belarusian on August 25, 1539, to a trusted servant in Vilnius, Szymek Mackiewicz (Mackevičius), Queen Bona commented on the alterations in the palace's loggia to be made by master Bernardo (after "Spółka architektoniczno-rzeźbiarska Bernardina de Gianotis i Jana Cini" by Helena Kozakiewiczowa, p. 161). This would explain later contacts of Constantine Vasily with Venice. Also the ancestral nest of the family - Ostroh was a multicultural city, where, apart from orthodox Ruthenians, many Jews, Catholics and Muslim Tatars also lived (after "Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski wobec katolicyzmu i wyznań protestanckich" by Tomasz Kempa, p. 18). In 1539, the struggle for the inheritance gained a new intensity after the death of Ilia and his wife Beata Kościelecka's entry into management of all estates. The protegee of Sigismund and Bona once accused Alexandra and her son of intending to seize all estates by force and she obtained from Sigismund a relevant decree to prevent it. In 1548 Princess Alexandra was mentioned in a letter regarding the appointment of the Kobryn archimandrite. Seven year later, in 1555, "Duchess Constantinova Ivanovitch Ostrozka, Voivodess of Trakai, Hetmaness Supreme of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Princess Alexandra Semenovna" had a case with Prince Semyon Yurievich Olshanski about mutual wrongs in the neighboring estates of Turov and Ryczowice and in 1556 she was granted the privilege to found a town on her estate of Sliedy. From February to June 1562, she conducted her own property and court affairs. She was still living in 1563 as on August 30, Duke Albert of Prussia addressed a letter to her, but on June 3, 1564, she was mentioned in the royal letter as deceased. Some researchers tend to think that it was Alexandra that was buried in Pechersk Lavra in Kiev next to her husband (after "Prince Vasyl-Kostyantyn Ostrozki ..." by Vasiliy Ulianovsky). The proud and fabulously rich Ruthenian princess, a descendant of Grand Princes of Kiev and Grand Dukes of Lithuania, could afford the splendor worthy of the Italian queen Bona and to be painted by the same painter as the queen. The young woman from a portrait by Bernardino Licinio in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (oil on panel, 69.5 x 55.9 cm, invenotry number Cat. 203) bear a striking resemblance to effigies of Alexandra by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop, indentified by me, especially her portrait as Venus (Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna) and in the scene of Hercules and Omphale from the Kolasiński collection, both dated '1531'. This portrait is dated to about 1530 and comes from the collection of an American corporate lawyer and art collector John Graver Johnson (1841-1917). The lady in a brown dress and an expensive necklace with a cross in Italian style around her neck, holds gloves in her right hand, accessories of a rich noblewoman.

Portrait of Alexandra Olelkovich-Slutska, Princess of Ostroh holding gloves by Bernardino Licinio, ca. 1531, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Portraits of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg, Queen of Sweden as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder

In 1526, the thirty-year-old king of Sweden, Gustav I Vasa (1496-1560), sent Johannes Magnus, Archbishop of Uppsala to matchmaking for a thirteen-year-old Hedwig Jagiellon (1513-1573), daughter of Sigismund I and Barbara Zapolya. However, as the ruler of a poor country, elected king three years earlier from among the Swedish lords, and leaning towards Lutheranism, he was considered too modest party for the Jagiellonian princess and this candidacy was rejected (after "Jagiellonowie ..." by Małgorzata Duczmal, p. 295). He also tried in vain to obtain the hand of the widowed Duchess of Brzeg, Anna of Pomerania (1492-1550), and earlier he was rejected by Dorothea of Denmark (1504-1547), who become Duchess of Prussia and Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1508-1541), later Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg, whose parents thought his reign was too unstable and he was heavily in debt.

Gustav was recommended to open negotiations with Saxe-Lauenburg. The duchy was considered rather poor but its dynasty was related to several of Europe's most powerful dynasties, including the House of Pomerania. The negotiations for the hand of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513-1535), second daughter of Magnus I, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg and Catherine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, began in 1528. Finally, with mediation from Lübeck, they were completed and in late summer 1531, Catherine was escorted to Sweden. The wedding took place in Stockholm on her 18th birthday, September 24, 1531. Almost a year before the marriage, on November 12, 1530, Catherine's father Magnus received the enfeoffment of his duchy from Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Augsburg. His wife, Catherine's mother, also Catherine, was considered a strict Catholic with close ties to her Brunswick relatives, which prompted Gustav I to marry her daughter to dissuade the German Catholic princes from supporting King Christian II of Denmark. Catherine's mother was also respected by the Emperor and the Jagiellons. She was depicted as Saint Catherine in paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop (National Gallery of Denmark, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe), together with Queen Barbara Zapolya (1495-1515) and Barbara Jagiellon (1478-1534), Duchess of Saxony. In 1531, Magnus spread the ideas of the Reformation in his duchy and became a Lutheran, like most of his subjects. For these reasons, their daughter could not be brought up as a Protestant, as some sources claim, and possibly converted to Lutheranism in Sweden. The marriage with Gustav Vasa was described as unhappy. In older Swedish historiography, Catherine is described as capricious, cold-hearted, and constantly complaining about all things Swedish. She had never learned the Swedish language either. Gustav himself only learned a little German, which made communication between the spouses very difficult. However, she fulfilled her dynastic duty and bore her husband a male heir to the throne named Eric, later Eric XIV, born on December 13, 1533. The first tutor of a young prince was a learned German, Georg Norman from Rügen. During a ball given in Stockholm in September 1535 in honor of her brother-in-law Christian III of Denmark, when Catherine was probably pregnant, the queen fell so badly while dancing with Christian that she became bedridden. She died the day before her 22nd birthday with her unborn child. Rumors claimed that Gustav murdered Catherine by hitting her on the head with an ax, after he learned from a spy that she had slandered him in front of the Danish king during the dance. Catherine was first buried in the Storkyrkan in Stockholm on October 1, 1535, and her body was moved in 1560 to Uppsala, where she was buried in the Cathedral along with Gustav and his second wife Margaret Leijonhufvud (1516-1551). Her effigy on the sarcophagus, carved by the Flemish painter and sculptor Willem Boy, is considered the most faithful, however the statue was created around 1571 in Flanders and sent to Sweden. In traditional historiography, Catherine has often been portrayed negatively as a contrast to Gustav's second wife, Margaret, a Swedish noblewoman, who has been presented as an ideal queen. The king married Margaret, on 1 October 1536, a year after Catherine's death. It is likely that she was a maid of honor to Gustav Vasa's first queen. Several portraits of Margaret survived, including the full-length effigy, attributed to the Dutch painter Johan Baptista van Uther, in which she was portrayed stereotypically for northern monarchs in rich costume and wearing crown jewels (Gripsholm Castle, NMGrh 434). The realism of this effigy suggests that it could be created in her lifetime, the author could be different and like the triple sarcophagus of Catherine, Gustav and Margaret it could be created in Flanders and sent to Sweden. No painted effigy of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg, made during her lifetime, is known. The portraits that have sometimes been identified as her likenesses are most likely portraits of Polish-Lithuanian noblewomen from the late 16th century (Gripsholm Castle, NMGrh 427, NMGrh 426). In 2013 a small portrait miniature of a lady in guise of naked Roman matron Lucretia was sold in London (oil on panel, 14.9 cm, tondo, Sotheby's, December 4, 2013, Lot 3). "Works such as this, most notably the portraits, seem to have been among the earliest German paintings to adapt the format of Renaissance medals or plaquettes", according to Catalogue Note. The painting most likely comes from the collection of the Dukes of Parma in northern Italy or Rome and later it was in the collection of Count Grigory Sergeievich Stroganoff (1829-1910) in Rome, Paris and Saint Petersburg. This provenance from the ducal collection in Italy suggests that the woman was an important international figure. Interestingly, the same woman, although dressed, is seen in a painting from the so-called Gripsholm suite or the triumphal paintings of Gustav Vasa, standing next to a man identified to represent the king himself. The paintings were probably commissioned by king Gustav or his wife to decorate one of the halls at Gripsholm Castle. The cycle is attributed to the local Swedish painter Anders Larsson, who in 1548 executed decorative paintings at Gripsholm Castle, but some undeniable influences from Cranch's works can be listed. This is particularly noticeable in the composition of the scenes and costumes, and the scene of a judgment with a woman falling to the ground supported by a man recalls the fable of the Mouth of Truth (Bocca della Verità) by workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, dated '1534' (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Gm1108) and especially the version of this composition from the Schloss Neuhardenberg from about 1530. Consequently, the authorship of Cranach's studio cannot be ruled out, also because the whole cycle is known from 18th century watercolors, created in 1722 by Jacob Wendelius (Royal Library in Stockholm), as the original paintings not preserved. Additionally, many authors compare the scenes to works from Wittenberg's workshop. Interpretations of the paintings' motif have long been debated. Some authors thought it was an allegorical depiction of the king's war of liberation against the Danes in 1521-1523 and the woman is a symbol of the Catholic Church - Ecclesia. The story of Virginia and Appius Claudius, Karin Månsdotter and Eric XIV, Catherine Jagiellon, when Eric was planning to extradite her to Moscow were also suggested and that they were not paintings, but tapestries. The interpretation that the cycle was textiles does not exclude the authorship of Cranach's workshop because, like the Flemish painters, they produced cartoons for tapestries. Nicolaus "the Black" Radziwill had a tapestry after Lucas Cranach's "Baptism of Christ in Jordan", which he orders to hang in the hall of his palace for royal reception in 1553 (after "Lietuvos sakralinė dailė ..." by Dalia Tarandaitė, Gražina Marija Martinaitienė, p. 123) and the so-called Croy tapestry, commissioned by Philip I of Pomerania and created by Peter Heymans in 1554 (Pommersches Landesmuseum), was most likely based on a cartoon by Cranach's studio. In his 2019 article ("Gripsholmstavlorna ..."), Herman Bengtsson suggested that "it is not unlikely that the paintings depicted the legend of Lucretia, which was very popular and widespread in Northern Europe during the early Renaissance", with reference to the inventories drawn up in the 1540s and 1550s. However, the suicide scene is missing. The inventory of Gripsholm Castle in 1547-1548 mentions a small painting with "Luchresia" in the wife's chamber and inventory of the Norrby royal estate in 1554 lists four large new paintings with scenes from Lucretia's story. According to Peter Gillgren ("Wendelius' Drawings ...", 2021) the cycle depict the biblical story of Esther and Ahasuerus and the paintings (or tapestries) were produced in Poland in the 1540s and could have come with Catherine Jagiellon. At the Turku Castle in Finland in 1563 there was "an old piece with the story of Hestrijdz", which Catherine most probably brought with her from Poland because it is not listed in inventories from previous periods. Another proposal is that the cycle originally belonged to Gustav Vasa's first wife, Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg, who evidently brought several lavish art objects with her to her new homeland (after "Gripsholmstavlorna ..." by Herman Bengtsson, p. 55). What is indisputable is the influence of the works of Cranach, costumes from the 1530s or 1540s and the predominant role of a woman. Her golden dress suggests she was a queen and the biblical or mythological disguise implies that she wants to emphasize her virtues. If we assume that this woman is Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg, then the residence in the miniature from the collection of the Dukes of Parma should be her palace. The building on the left almost perfectly matches the large manor house (Stora borggården towards the east) of the Tre Kronor Castle in Stockholm, as depicted in a print from about 1670 by Jean Marot - Arcis Holmensis Area versus Orientem. Two windows and a rounded door are almost identical. The medieval castle was rebuilt and extended after 1527. During the reign of John III, the structure was rebuilt again by Dutch architects who made larger windows and built the castle church. Catholic chapel of John III's consort, Catherine Jagiellon, was installed in the northeast tower. Tre Kronor was destroyed in the fire of 1697, and the current Stockholm Palace was later built on the site. The same woman in a similar pose was depicted in another painting of Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder, today in the Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki (oil and tempera on panel, 38 x 24.5 cm, inventory number S-1994-224). At the end of the 18th century it was possibly in a private collection in Finland. The painting is signed with artist's insignia (winged serpent) and dated '1530' on the left. Catherine was married to Gustav Vasa in 1531, however, preparation for such an important event as the royal wedding took time, which is why the marriage contract was most likely signed at least a year earlier. Although many items for the bride's dowry were collected throughout her young life, the more exquisite clothing, jewelry, and items fit for a queen must have been prepared and ordered shortly before the wedding. The trained eye will spot in the form of the castle on a fantastic rock behind her the building important for the history of Finland - Turku Castle viewed from the harbour. It was founded in the 1280s as an administrative castle of the Swedish crown. The castle's heyday was in the 1560s during the reign of Duke John of Finland (future John III) and Catherine Jagellon. As in the virtual reconstruction of the castle between 1505-1555, we can see two main towers and the main residential building on the left. Like the portrayed person, Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg in the guise of Lucretia, the castle is also disguised, so this is probably not an exact appearance of the structure in 1530, however no view of the castle from that time has survived, so we cannot rule out that the tower originally had such a tall Nordic-style spire. Renaissance painters, especially in Italy, loved such riddles. The viewer must therefore strain his mind and find the true meaning. The "obvious things" were sometimes not so obvious, such as that Leonardo's Mona Lisa was probably not a woman and Raphael's Young Man from the Czartoryski collection was probably not a man. This painting was created for purely propaganda purposes. In the 1530s, Gustav Vasa started to bring in German officials, along with whom new visions of royal power arrived. In 1544, the monarchy was changed to hereditary and Gustav's eldest son Eric was named heir to the throne. So this painting is like a message: look my subjects, you will have a beautiful and virtuous queen, like the Roman Lucretia. She is healthy and will bear healthy sons. Our monarchy will modernize and the most famous German painting workshop created the effigy of your future queen. Another similar Lucretia by Cranach dated '1532' is in Vienna (oil on panel, 37.5 x 24.5 cm, Academy of Fine Arts, GG 557). It comes from the collection of an Austrian diplomat and art collector, Anton Franz de Paula Graf Lamberg-Sprinzenstein (1740-1822), who spent six years in Naples where he collected over 500 ancient Greek vases. In 1818, after retiring from the diplomatic service, he bequeathed to the Academy of Vienna his entire painting collection, including works by Titian and Rembrandt. We cannot exclude the possibility that this painting comes from the collection of Queen Bona Sforza, whose collections were moved to Naples after her death in Bari in 1557. In all mentioned paintings, the model's face resembles the effigy of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg from her tomb in Uppsala Cathedral, as well as effigies of her only son Eric XIV by the Flemish painter Domenicus Verwilt. The Duchess of Saxony Barbara Jagiellon was depicted as Lucretia and the majority of Gustav's potential wives - Hedwig Jagiellon, Anna of Pomerania and Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin were depicted as nude Venus in Cranach's paintings. The Queen of Sweden followed the same fashion of mythological disguise in her portraits.

Portrait of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513-1535), Queen of Sweden as Lucretia against the idealized view of Turku Castle by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530, Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki.

Miniature portrait of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513-1535), Queen of Sweden as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530-1535, Private collection.

Portrait of Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513-1535), Queen of Sweden as Lucretia by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

Portraits of Dukes of Pomerania and Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg by Lucas Cranach the Elder

On January 23, 1530 in Berlin, Duke George I of Pomerania (1493-1531), son of Anna Jagiellon (1476-1503), sister of Sigismund I, married Margaret of Brandenburg (1511-1577), daughter of Joachim I Nestor (1484-1535), Elector of Brandenburg.

Margaret brought a dowry of 20,000 guilders into the marriage. She was quite unpopular in Pomerania due to Brandenburg's claims to Pomerania. In 1524 George crafted an alliance with his uncle King Sigismund I, which was directed against Brandenburg and Duke Albert of Prussia and in 1526 he went to Gdańsk, to meet his uncle and paid homage of Lębork and Bytów, thus becoming a vassal of the Polish crown together with his brother Barnim IX (or XI) the Pious. George died a year after the marriage on the night of May 9 to 10, 1531 in Szczecin. He was succeeded by his only son Philip I (1515-1560), who became a co-ruler of the Duchy alongside his uncle, Barnim IX. Few months later on November 28, 1531 Margaret bore a posthumous child, a daughter named after her father Georgia. As a result of the division of the principality, which took place on October 21, 1532, Philip I became the Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast, ruling over the lands west of the Oder and on Rügen and his uncle Barnim IX, the Duke of Pomerania-Szczecin. As the lands of Margaret's jointure/dower, a provision after the death of her husband, were in Pomerania-Wolgast her stepson had to sort out the relationship with his unloved step-mother and to levy a special tax to pay her dowry and redeem her jointure. On February 15, 1534 in Dessau she married her second husband Prince John IV of Anhalt (1504-1551) and on December 13, 1534, Philip and Barnim IX introduced Lutheranism in Pomerania as the state religion. Barnim IX was a renowned patron of arts and brought many artists to his court. He also collected works of art and he, his brother and nephew frequently commissioned their effigies in Cranach's workshop. The so-called "Book of effigies" (Visierungsbuch), which was lost during World War II, was a collection of many drawings depicting members of the House of Griffin, including preparatory or study drawings by Cranach's workshop. In February 1525 Barnim concluded an alliance with the House of Guelph by marrying Anna of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1502-1568), daughter of Henry the Middle (1468-1532), Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Margaret of Saxony (1469-1528). Henry, who sided with the French king Francis I during the Imperial election, and so earned the enmity of the elected Emperor Charles V, abdicated in 1520 in favor of his two sons Otto (1495-1549) and Ernest (1497-1546), and went into exile to France. He returned in 1527 and tried to regain control of the land. When this failed, he went back to France and returned only after the imperial ban was lifted in 1530. Henry spent his last years in Wienhausen Castle, near Celle, where he lived "in seclusion" and died in 1532. He was buried in the Wienhausen Monastery. A few days after the death of his wife Margaret of Saxony on December 7, 1528, he entered into a second, morganatic marriage in Lüneburg with Anna von Campe, who had been his mistress since 1520 and who had previously borne him two sons. In autumn 1525, Henry's eldest son Otto secretly and against his father's wishes married a maid-in-waiting of his sister Anna, Mathilde von Campe (1504-1580), also known as Meta or Metta, most probably a sister of Anna von Campe. When Otto renounced participation in the government of the principality in 1527, Ernest became sole ruler. In 1527 with the advent of the Lutheran doctrine to Brunswick-Lüneburg, the life of Otto's and Ernest's sister Apollonia (1499-1571) change fundamentally. She was born on March 8, 1499 as the fifth child of Duke Henry the Middle and Margaret of Saxony. When she was five years old, her family sent her to the Wienhausen Monastery. At the age of 13 Apollonia was consecrated, and at the age of 22 she takes her religious vows. Ernest summoned Apollonia to Celle, on the occasion of her mother's planned trip to relatives in Meissen. Her brothers and her mother urged her to change her religion, but Apollonia refused. Back in Celle, where she was the educator of the ducal offspring, she met Urbanus Rhegius, the reformer and her brother's theological adviser. He become her spiritual partner and brought her closer to the new doctrine. Nonetheless, she remained Catholic. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 Ernest signed the Augsburg Confession, the fundamental confession of the Lutherans, and George and Barnim received the imperial enfeoffment. Despite the opposition of the entire community, the Wienhausen Monastery was transformed from a Roman Catholic into a Lutheran establishment for unmarried noble women (Damenstift) in 1531. Duke Ernest, like Barnim, also commissioned portraits from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder. His portrait by Cranach's workshop is in Lutherhaus Wittenberg, and a study drawing to a series of portraits is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Reims. Ernest married Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1508-1541) on June 2, 1528. She was a daughter of Duke Henry V (son of Sophia of Pomerania) and Ursula, daughter of Elector John Cicero of Brandenburg. A portrait of young woman in guise of Judith comes from the old collection of the Grunewald hunting lodge (Jagdschloss Grunewald), near Berlin. This Renaissance villa was built between 1542 and 1543 for Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg, elder brother of Margaret of Brandenburg. The painting is dated 1530, below the window, a date when Margaret become the Duchess of Pomerania and the castle visible in distance is similar to the Klempenow Castle, which was part of Margaret's jointure. The same woman was also depicted as Venus with Cupid stealing honey in a painting by Cranach the Elder from the private collection in London. She is wearing bridal wreath with a single feather on her head, thereby announcing that she is ready for marriage. The painting is very similar to portrait of Beata Kościelecka as Venus from 1530 in the National Gallery of Denmark and it is dated "1532" on the trunk of the tree, a date when Margaret was already widowed and her stepson wanted to get rid of her. In the same year, she was also represented in a popular courtly scene of Hercules with Omphale. Two partridges, a symbol of desire, hang directly over her head and her face features are very similar to the effigies of Margaret's father and siblings. Above the woman opposite there is a duck, associated with Penelope, queen of Ithaca, marital fidelity and intelligence. This symbolism as well as woman's effigy match perfectly Anna of Brunswick-Lüneburg, who became a driving force behind the division of Pomerania in 1532 and who considered that George's intent to marry Margaret of Brandenburg threatened her own position. The man depicted as Hercules is therefore Anna's husband, Barnim IX. The painting is dated 1532 below the inscription in Latin. It was acquired by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin before 1830 and lost in the World War II. The capital of Germany was the city where many items from the collection of dukes of Pomerania were transferred, including the famous Pomeranian Art Cabinet. Another painting depicting Hercules and Omphale created by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1532 was also in Berlin before 1931 (Matthiesen Gallery), today in private collection. It is very similar to the painting showing Barnim IX, his wife and his sister-in-law and it have similar dimensions (79 x 116 cm / 82.5 x 122.5 cm), composition and style. In this painting two partridges hang only over the couple on the left. The man is holding his right hand on the breast and heart of a woman, she is his love. The young woman to the right is placing a white cloth over his head like a bonnet in a way of engaging with him like a sister. The older woman in a white bonnet of a married or a widowed lady behind her is handing Hercules the distaff. It is therefore their mother or stepmother. Consequently the scene depict Ernest I of Brunswick-Lüneburg, his wife Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, his sister Apollonia and their stepmother Anna von Campe. The two young women from the latter painting were also depicted together in a scene of Judith with the head of Holofernes and a servant from the late 1530s. This painting, today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, comes from the Imperial Gallery in Prague (transferred before 1737), therefore it was sent to or acquired by the Habsburgs. The same woman as Judith is also represented in a painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, acquired in 1911 from the collection of Robert Hoe in New York. Her face features are very similar to effigies of Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, her father and sons.

Portrait of Margaret of Brandenburg (1511-1577), Duchess of Pomerania as Judith with the head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530, Grunewald hunting lodge.

Portrait of Margaret of Brandenburg (1511-1577), Duchess of Pomerania as Venus with Cupid stealing honey by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, Private collection.

Portrait of Barnim IX (1501-1573), Duke of Pomerania, his wife Anna of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1502-1568), and his sister-in-law Margaret of Brandenburg (1511-1577) as Hercules and Omphale's maids by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, lost.

Portrait of Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1508-1541), Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg as Judith with the head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Portrait of Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1497-1546), his wife Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1508-1541), his sister Apollonia (1499-1571) and stepmother Anna von Campe as Hercules and Omphale's maids by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, Private collection.

Portrait of Sophia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1508-1541) and her stepsister Apollonia of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1499-1571) as Judith with the head of Holofernes and a servant by Lucas Cranach the Elder, after 1537, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Portraits of Beata Kościelecka by Lucas Cranach the Elder and Bernardino Licinio

"O Beata, adorned so rich in rare charms, You have a virtuous and honest speech, The worthy and unworthy of you still adore you, The gray-haired, though prudent, they go crazy for you" (O Beata decorata rara forma, moribus / O honesta ac modesta vultu, verbis, gestibus! / Digni simul et indigni te semper suspiciunt / Et grandaevi ac prudentes propter te desipiunt), wrote in his panegyric modeled on the hymn in honor of the Virgin Mary, entitled Prosa de Beata Kościelecka virgine in gynaeceo Bonae reginae Poloniae (On Beata Kościelecka a maiden in the household of Bona, Queen of Poland, II, XLVII), Andrzej Krzycki (1482-1537), Bishop of Płock and secretary of Queen Bona.